From Chapter Nine: The Movimiento.

The Autobiography of Esteban Torres As Told To Michael Sedano

Michael Sedano

There’s a reason Esteban Torres remains el movimiento’s unsung hero: no one’s sung his song, though there are chapters and essays by other people that circle around the man and his career. No one can sing what only Esteban remembers, so right now, Esteban and I have the music, we need a publisher.

And we need the pandemic to abate to reopen the possibility of writing part two of Esteban Torres’ story. That’s the part where he becomes a United States Ambassador, then Jimmy Carter’s White House organizer for all things raza. When Jimmy loses, Torres comes home, runs for the House of Representatives. He serves eight terms in Congress. In Torres' view, he is the first Chicano in the House. He was elected to serve with a couple of Mexican Americans, they weren't Chicanos, he says.

I devoted two years before plague-time hit, in weekly meetings with Esteban Torres and wife, Arcy, and various adult kids. Loquacious Torres, meet Loquacious Sedano. We met memory limits, too. These memories happened so long ago, it sure doesn't seem like yesterday. It wasn't. So it goes.

Part One of Esteban Torres’ Autobiography As Told To Michael Sedano recounts the early chronology growing up in East Los Angeles, graduating Garfield High, joining the Army for six years occupying Germany and guarding the eastern front. Returning from the Army on the eve of the Korean war, Love happens and Torres lands a good solid Union job welding together Plymouths in South Gate. From there, Union leadership takes him to Washington, D.C. and international organizing. He's the first Chicano, the Only Chicano, he fits in and succeeds in good times and hard, and he knows why.

Chapter Nine brings Torres back home to ELA. He has a mission from the Union. Use the model of trade unions to fashion community growth through mutual ownership. Thus TELACU in its original conception happens and does good, especially helpful to the burgeoning movimiento. They occupied the identical community space. This is how Chicanas Chicanos fight the War on Poverty.

Bert Corona and Esteban Torres vie to lead Congreso, a coalition of dozens of activist groups pursuing diverse causes para el pueblo. Torres is elected and he’s in the position to finance demonstrations that culminate on August 29, 1970.

In this excerpt from the movimiento chapter, Torres recounts the aftermath of August 29. Follow along as Sedano reads the text with you.

From Chapter Nine: The Movimiento.

The Autobiography of Esteban Torres As Told To Michael Sedano

Michael Sedano

As the leader of Congreso, responsibility came to me to make sure the permits were in place. The committee had secured our right to march. But it wasn’t free. You have to buy permits for Free Speech.

I had the honor of walking into Los Angeles County Hall of Records and signing a check from the Congress of Mexican American Unity. The Chicano Moratorium march of August 29, 1970 had its permit. We were marching.

The August 29, 1970 Chicano Moratorium without question is the most well-known event of the Chicano Movement because it ended in a police riot. In the course of the day, three Chicanos were killed by sheriff or police…..In East Los Angeles, Ruben Salazar was killed by a Sheriff Deputy. In Los Angeles, Angel Díaz and 14-year old Lyn Ward, were shot by LAPD.

A Coroner’s inquest into the shooting of journalist Salazar held Southern California television audiences glued to their sofas. …. “The Coroner to the Stars,” Thomas Noguchi, and his staff, shared spell-binding testimony with law enforcement experts and street-level agents.

The march and killing came under a microscope, the community’s complaints about police brutality were placed on the record and spoken on live television to millions of people who knew “East LA” only as a phrase.

The Coroner concluded Salazar’s killing was a homicide, a man was dead at the hands of another man. The Deputy who fired the gun was not indicted.

The East LA antiwar protest killings followed a pattern. Earlier that year, 3 were killed at Jackson State University, and before that, Kent State University. El Pueblo Unido Jamas Sera Vencido, but at the same time we didn’t want to get shot to be heard.

Despite the fervor of our intentions, after August 29th there was significant shrinkage of public support. Congreso and the Moratorium Committee did not abandon the message nor abandon marching as a communication tactic. We experienced some push-back from the community, however.

. . .

The Comité Civico Patriotico, the club that organizes the 15 de Septiembre parade, said we—Congreso and the Moratorium Committee—weren’t welcome at the quince de Septiembre parade down Whittier Boulevard.

Conservative Mexicanos, they feared our activism, they saw our goals as unpatriotic. There clearly existed a cultural and a generation gap. But we shared cultura and that was enough to open a door. Comité invited us to state our case in a public meeting.

Once again, Rosalio and I were the portavozes for the Moratorium Committee. We heard their side; the Consul General of Mexico would be there, the Chamber of Commerce, the Lions Club, all manner of civic organizations. Why would they want our group in the line of march?....

Even the most conservative American of Mexican descent understood the unequal burden the Draft and the Vietnam war placed on the community. And that had been the focus of August 29. We urged them not to allow police rioting to silence our demands against the war and all our dead Chicano GIs.

The Comité Civico Patriotico said we could march. But we had to remain twenty yards behind their last official float.

That’s where we marched on 15 de Septiembre, 1970. Two weeks earlier, thousands took to the street. There were only thirty of us.

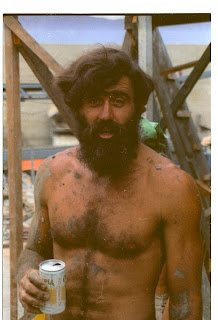

Our spirits remained strong. There’s a funny photograph of our team marching back there behind the floats and bands. Rosalio, Richard Martinez, Max Avalos, and I are in the front of our group. I’m gesturing my happiness that once again, speaking up was the route to effectiveness. We understood the Comité as people and neighbors. We offered good reasons to let us march. My team had a spot in the big parade. My upraised fist said “We fight and we win and we do not give up. Y que?”

Oracy & Written Words

"What do I do with my video, once I've recorded my Best 2 Minutes reading my own stuff?

Save your video with Public settings on the Face, or Vimeo, or any site where La Bloga can link for the world to share. Send a Link via email to msedano@aol.com. Include your mailing address to receive acknowledgement of your entry in La Bloga's 100,000 Poets For Change 2021 event.

Here are details (link) on the "My Best 2 Minutes." Celebrate Oracy through an effective, considered, oral reading of your own work. Additional details in two more links below.

https://labloga.blogspot.com/2021/08/augusto-al-gusto-reading-your-stuff.html

https://labloga.blogspot.com/2021/08/my-best-2-minutes-kmart-farewell.html

Esteban Torres' autobiography is written in conversational style. More formal, academic-scented narratives, offer readers the "he said she said" challenge, of using only the vocal expression of printed text to change speakers and characters.

Nonverbal behaviors offers visual cues, like holding a fist in the air as the text reads. Think radio. Hold that fist high overhead, but hold it in the sound of your voice visualizing that hand against the sky. We can't see you on radio. But we sure can hear you. In general, audiences hear what the reader sees.