From the Publisher: Alejandro Morales debut collection, Zapote Tree, includes 34 poems reflecting upon childhood, family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, historical figures, mythical beings, metaphysical entities, serpents, ghosts, heroes, villains, and the dispossessed. Weighty topics, like autocracy, racial injustice, and artificial intelligence, mix with good-humored, witty portraits of his wine-drinking dog, overachievers, and slacker repairmen. Zapote Tree's pathos and gritty depictions of social outcasts are balanced by Morales' joyful celebrations of loyalty, love, and resilience.

Q: You are the acclaimed author of about 20 books-- novels, short fiction, and nonfiction—written over a decades-long career. Why did it take so long for you to decide to write a book of poetry?

I have been writing poetry since middle school, high school, and college, through the present. At first, I wrote short paragraphs or verses about what I saw, felt, experienced. As I learned more about poetry, my poems became grounded, structured, and guided by my experiences and what I learned about the craft. This book is a compilation of poems that I wrote throughout 60-plus years of my life.

The idea to put together a collection for publication came a few years ago when I met with an author friend and book publisher and asked her to take a look at some of my poems. After a while she said, “You have enough for 3 or 4 books of poems here.” I felt the time had finally come to put my writings into my first poetry book!

Q: Why did you choose Zapote Tree as the title of your debut poetry book?

Because the zapote tree was always there, watching over me as I grew up, during good and bad times: physically there in my neighbor’s yard in my childhood with me greeting the giant, lush tree each morning when I walked out the back door of my house. As the years passed, I imagined the zapote tree “observing” my physical, intellectual, spiritual, and creative development. The power of its nurturing memory became a kind of spiritual touchstone, an inspiration, in my life.

Q: Women comprise a sizable portion of the characters in your book. Why is that, and how do you think readers will react to these varied individuals?

The women in this book all have something special about them and perhaps readers, women and men, will see at least an aspect of themselves in these women who are wives, daughters, mothers, celebrities, heroes. The poems embody their suffering, their joys, achievements, ingenuity, spirituality, bravery, and triumphs. In my family and community, I always saw women as intelligent, powerful, mystical, and inherently beautiful.

Q: The son of immigrants, you are still very close to your Latino roots, especially your native language. Several of your poems have lines or stanzas in Spanish and a few bilingual renditions of poems. How does bilingualism affect your poems and writings in general?

I don’t consider myself traditionally bilingual. Yes, I speak Spanish; but, I’m English-dominant. The first language I heard was Spanish, and I didn’t start learning English until kindergarten. My entire education was in English. Throughout my schooling, as I learned more English words, I sadly lost Spanish words.

But this created a coalescence of both languages that ultimately became the language that I speak and write in now. If you listen to the way I speak and if you read my books, you will find a strange syntax, word usage that is neither Spanish nor English but a combination of both. I consider this coalescence unique and feel that this combining gives my works an unconventional view of the world.

Q: What was your biggest challenge generally in writing the 34 poems that comprise this volume?

Editing the poems to fewer words. A main quality of poetry is to say more with less. The process of editing is iterative and cumulatively improves the work. No matter the genre of your writing, editors help you see what you don’t see as the creator, and I was able to work with three excellent editors at three stages of development.

It took more than a year of editing to get this book ready for publication, from idea, research, first draft, multiple drafts with significant restructuring, multiple galley proofs, and finally the release of the book. This book creation process usually takes me 4 to 5 years. What I find amazing about Zapote Tree’s production is that all this was accomplished in less time.

Q: How can Latinx authors gain more widespread recognition for their work, more mainstream exposure?

First, I hope readers are aware that Latinx writers are often considered one-theme authors and are expected to write only from their racialized identities. However, Latinx writers are highly diverse and explore universal themes, just as authors from any ethnic background. Latinx writers—in fact, all Latinx people— are not monolithic. Yet editors, publishers, others responsible for producing books, might “pigeonhole” us more than they think.

For example, I once wrote a speculative story for an anthology of Latinx speculative stories. My narrative, which the selections committee for that book praised, was based on memory theories and was scientifically grounded. Eventually it was rejected because, I was told, “it was not Chicano enough” and the characters “didn’t have Chicano names.” These editors had put Latinx writers in an ethnic cubbyhole instead of letting us be free to write about whatever interests us. Don’t let editors like these stifle our identities and versatility.

Alejandro Morales earned his B.A. from California State University, Los Angeles, and a M.A. and Ph.D. from Rutgers University.

Morales is an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Chicano/Latino Studies at the University of California, Irvine. His 20 published books include: The Brick People (1988); The Rag Doll Plagues (1992); River of Angels (2014); and Little Nation & Other Stories (2014). Morales received the prestigious “Luis Leal Award for Distinction in Chicano/Latino Literature” in 2007 from the University of California, Santa Barbara. He lives in Santa Ana, California and is now working on three projects: a biographical novel, a collection ofshort stories, and another book of poetry. Morales is considered a pioneer in American Latino literature, being one of the first authors in the 1970s to depict harsh socioeconomic conditions of barrios and to create Chicano cultural testimonies and metanarratives.

Kathy and Jim Build a Boat. Boatyard chile verde.

Durf marveled at his teammate, a javelin thrower who lived in the Goleta monte. A born storyteller, my roommate spun a fanciful tale of a man I knew only by sight from track meets. I sought what germ of truth must lie at the heart of Durfee’s account.

|

| Jim Clark back to camera. Barbara Sedano at right. |

Jim Clark’s girlfriend, Kathy, loved him with immense dissonance. Jim’s life was impossible to share with a woman studying to make a career teaching high school English. It was during one of their off-again separations that Kathy and I were hanging around together.

Kathy filled whatever space she occupied. Not many people chose to occupy space with her, however, because Kathy spoke her mind. A woman of wit and brains, Kathy was a formidable personality who fit perfectly into my world, especially as we both were single and not looking. An ideal end-of-college-summer partnership.

Four years have ways of changing a person’s life and attitudes. I was back from overseas and learned from the locals that Kathy and Jim lived in the boatyard along the railroad tracks. They were building a boat and needed help. I called the boatyard. I hadn’t heard Kathy’s voice in four years but I recognized her “hello?” instantly and she mine. Old friends are good friends, separations are meaningless.

I asked him about the javelin story. “I tried it one time,” Jim Clark laughed. That was the day we laid the keel for the cement boat.

|

| Kathy looks out while Jim and friend cement the deck. |

I drove the car into the weeds where Jim directed me to stop with the rail underneath. Jim and another fellow lifted the front end and I lashed it to the front bumper. We did the same on the other end.

The nose of the rail extended a few feet from both ends of the Buick Skylark. Slowly and not spotted by cruising cops or railroad dicks, we drove the back streets to the boatyard and dropped the keel in place. In the boatyard shack’s two-burner propane stove, Kathy made her famous dumpster soup and we feasted friendship, old times, the cement boat to be.

A few months after, the boatyard shack has gained a dining table, an outdoor couch and several makeshift seats. Where we’d dropped the keel now stood a rebar and steel wire superstructure of a 40-foot boat. Jim worked on that boat with the intensity that led him to think he could chase down a deer and kill it with his javelin. The deer was certainly out of reach but Jim had built a boat. All it needed now was a skin of cement.

Months passed as Jim constructed the hull, deck, interior spaces and hidden recesses. The work took the time required. Ugency arrived with cementing. The work must be completed in one weekend so the boat dries and cures as a single mass of cement and steel that floats on the open sea. Friday after work, Barbara and I drove up from Temple City. The work was well underway by our arrival late afternoon. Jim and Kathy had lots of friends.

|

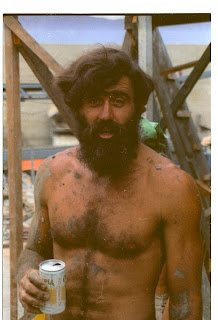

| Jim Clark. qepd. |

The third day the hull looked like a boat. Only a few people fit inside so workers took shifts pounding cement into the interior walls. Others touched up the exterior. By noon Sunday, the cement boat was done. Most of the crew had left, exulting in knowing they’d joined the culmination of an incredible feat. Jim had read books and talked to old salts, he and Kathy moved into the boatyard, and they built that boat by hand.

I volunteered to make the celebratory feast, a one-dish meal I call Boatyard Chile Verde. After Jim and the cement boat were taken by pirates in southeast Asia, Kathy sailed those waters in hopes of word. She cooked Boatyard Chile Verde for merchant mariners the world over, it was the crew’s favorite dish.

You can make this on a one-burner propane stove, or in a sartén over an open fire. Ingredients, improvisation, and preparation are the keys to making Boatyard Chile Verde.

Michael Sedano's BOATYARD CHILE VERDE

Pork. Sub beef or chicken.

Gf flour.

Tomatillos.

Green chile – hatch, California, mild new mexico, canned whole are fine.

El pato hot sauce.

comino

Onions

Garlic.

Cilantro

Cast iron frying pan and lid.

Paper or plastic bag.

Sharp knife.

Salt

Pepper

Chile powder

Olive oil

Into the bag, put a ¼ cup of gluten-free flour, a pinch of salt, pepper, and chile powder.

Wash and dry the (pork) meat.

Cut the meat into ½” cubes.

Dust the meat with seasoned flour in the bag.

Dice a large onion and six or eight garlic segments.

Chop cilantro to make 1/8 cup.

Chop 6-8 large tomatillos

Get 1/8” of olive oil hot in the pan. High flame.

Wilt the onion and garlic, stir don’t burn.

Toss the meat cubes with the wilted onions and garlic.

Season with salt, pepper, ground comino or a pinch of seed.

Brown.

Add the chopped tomatillos and chopped fresh/canned chiles, and the can or two of el pato.

Stir and cover.

Lower heat to medium and bring to a boil.

Lower heat to lowest simmer setting and cook for an hour, stirring now and again.

This is ready to serve right away. The objective to fork-tender bits of meat that look like meat, not a paste. Cook vegetable longer before adding chicken, then simmer raw chicken fifteen or twenty minutes until firm. Chicken is fast. Cook beef an hour and a quarter, maybe longer.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you! Comments on last week's posts are Moderated.