|

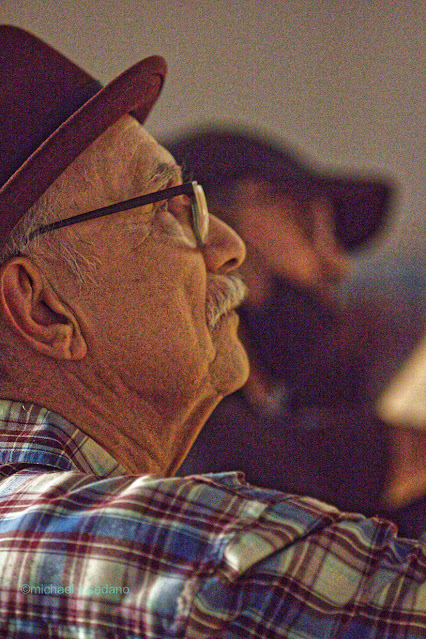

| Passing on a lesson from generation to generation |

It was in the summer of 1958, Pacific

Ocean Park’s opening, drawing 20,000 people. Word got around fast. The next day

nearly 38,000 people showed up, even surpassing Disneyland’s summer attendance.

I was nearly twelve, and I begged my mom to let me go with my friends, giving

her the old argument, “Everybody is going.”

POP was a state-of-the-art amusement

park, built on a large pier, straddling the Pacific shoreline, in Ocean Park, a

seaside suburb of Los Angeles, right beside the old Aragon Ballroom and Dome

Theater, two establishments entertaining folks going back to the era of big

bands and epic Hollywood movies. Ocean Park and neighboring Santa Monica had been drawing

beach-going crowds, way back to the early days of Los Angeles, people escaping

the inland heat, but now POP was built for the new baby boom generation

POP didn’t only have an enormous roller

coaster, rivaling the monster at Long Beach’s New Pike, but POP had all the newest

rides and amusements, as well as a pavilion which featured live rock ‘n roll

bands, big names as well as local bands, in those days, usually a four-piece

band, bass, guitar, drummer, and a sax player, topped off by Battle of the

Bands extravaganza. Wink Martindale, a rock ‘n roll radio and television host

would be broadcasting his show—live, from POP’s porpoise aquarium. I had to go.

After pestering her for days and telling

her exactly which of my friends was going, she relented, but only after telling

me she would be the one to drive us and pick us up.

She didn’t have a hard time verifying the

truth. My best friends, all of us interested in sports and music, lived either

two houses down or someplace close by. She knew I didn’t hang out with any

hoodlums in the neighborhoods, leftovers from the pachuco days, or the kids who

trouble always seemed to find. My mother was a woman of mantras, as she once said, handed down from my Mexican grandmother, one generation to another. The one I heard most often was, “Dime

con quien andas y te dire quien eres,” something like, “Tell me who you’re

with, and I’ll tell you who you are.”

So, the big day came, a Saturday. She

dropped us off about 3:00 P.M., in the family’s used light green ’53 Chevy. She

said she’d be back at 9:00 P.M. “sharp” to get us. I had about seven dollars in

my pocket, mostly money I earned helping my uncle and older cousin in their gardening businesses in Westwood, and a couple of dollars my mom pitched in for me

cutting the lawn and pulling weeds in our yard each Saturday morning.

The rides were expensive, twenty-five

cents each, and with food, the money didn’t go far. Luckily, a lot of

the other stuff, like the bands and exhibitions were free. As darkness fell, I reached into my empty pockets, hoping to find a

wayward quarter somewhere deep down, but no, nothing.

POP had been something of a family

reunion. I ran into a lot of people I knew, many of my older cousins, their friends,

and girlfriends. I’m not exactly sure how it started, but I think one of my

cousin’s, Leo, asked how I was doing. I must have said something like, “Great,

except I ran out of money.” Leo reached into his pocket, pulled out a quarter,

handed it to me, and told me to have a good time. Man, that was easy. I thanked

him and before long I ran into another cousin, asked to borrow a quarter, then

another, same thing, and before I knew it, I was rolling in quarters. I rushed

off to get on as many rides as I could.

At nine, sharp, my friends and I met my

mom right where she said she’d be waiting for us. Of course, she could see from

the beam in my eye I’d had a good time. She didn’t ask me much more. My mom,

and dad, had a way of getting us, kids, to talk. They would wait a day, until

the stories simmered then ask us how it went.

I remember telling my mom everything I’d

done, the rides, the bands, the radio station, the music, etc. etc., oh, and

seeing so many of my cousins there, of which she wasn’t too happy because,

though she loved all my relatives, she wanted me to stay clear of those with bad

reputations in the neighborhood.

When she asked if I’d had enough money, I

was honest, telling her I’d run out. I have no idea why, but I told her,

proudly, how I’d borrowed quarters from a few cousins I’d run into. She flipped

out! I can’t remember what she said, exactly, only that it was definitely a

scolding, and a lecture, and ending with something like I’d better never borrow

money from anybody again—ever! “If you can’t afford it, you don’t buy it.”

We were quiet. Finally, she told me to

make a list of everyone who had lent me money. When I finished, there were

probably eight to ten names on the list, all older cousins who lived in

the neighborhood. I remember her gathering up a bunch of quarters and giving

them to me. She said I was going to return the money today. She’d drive me to

each of their homes, and wait as I apologized for borrowing the money, and

pay them back.

“Apologize?” I was scandalized. I’d be

humiliated. I didn’t actually think I’d have to pay them back. I mean, it

wasn’t about the money. If they’d have asked me, I’d have given it to them and not

expected to be repaid. It was just a quarter, and, besides, we were family, at

least that’s what I thought.

Desperate, I promised my mother I’d work,

save the money, and repay them on my own, when I saw them at the park, or in

the neighborhood. She was angry, furious, really, like I’d stolen the money.

She said I had to return the money today, to not even wait another day.

So, there we went. She pulled right in

front of each home, and she waited in the car as I walked to the porch, knocked on the

door, and dropped the money into my cousin's palm. A few of them were surprised

and didn’t want to take the money. I told them I had to pay them back. They

waved to my mother as I walked back to the car. She smiled and waved back, like

everything was fine.

I was nearly a teenager, at the time, my

cousins in their mid to late teens. Even if some had already gotten into

trouble with the cops, I still looked up to them. They were handsome Chicanos, out

in public, hair immaculate. They were often decked out in pressed khakis,

spit-shined French toes, and Sir Guy shirts, or Pendletons. They

always had a girl on their arm, or so it seemed. Some even had cars. I shrank that day, placing

a quarter into their palms, my mom’s lesson reminding me I was still a kid.

“You don’t live beyond your means,” is

what she’d always say. “If you don’t have it, you don’t buy it.”

My grandparents came from Mexico’s

interior, during a revolution, five kids in tow, and they arrived in the U.S.,

minus one child who died in route. They had little money. Like many Mexican

immigrants, of the time, they worked hard, saved, collected money from each

working-age child, budgeted, bought a home, and started a new life without

borrowing from anybody. Borrowing was a sign of “gente baja,” like exposing

your business out in public for everyone to see.

My grandparents’ story ran deep in my

mother’s psyche, their struggles, their hard labor, and my grandmother’s

saying, “If you make a dollar, you save fifty-cents.” A Chicana of the WWII

generation, a cultural modernist, yet a fiscal conservative, it took my mother many

years to even apply for a credit card, and when she finally did, she made sure

she paid it off each month, explaining how the interest kept the borrower in

debt and made the lender rich.

She wasn’t a financial prude. She borrowed

to buy our first home, preferring to take out a G.I. Loan, from the government,

rather than a loan from a bank, which wanted to stretch the payments out over a

longer period and collect more interest. Luckily, neither she nor my father had

a need to buy expensive cars, clothes, or home furnishings, the financial

downfall for many families, so, like any responsible business manager, she had

a “reserve” in the bank. My mother’s preference was antiques, a connoisseur of early

colonial American, and she’d wake at 5:00 A.M. each weekend to be the

first at the estate sales in Beverly Hills and Bel-Air. She liked the idea of

keeping history alive.

For a time, my generation rejected the

artificiality of commercialism. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, most students in

America’s universities majored in humanities, the arts, and the social

sciences, reading the great minds, and hoping to make the world a safer and better place. We converted vans

into mobile homes and traversed the country, socializing, communing with nature, and seeking solace as our

government waged an unjust war against a smaller country. Many returning

veterans, who witnessed the ravages of war, firsthand, came home and shunned

1950s materialistic, militarist, industrial society.

Somewhere along the line, everything tanked,

our values and our morals. We picked up debt like everybody else. Our

happiness became about money and possessions, pitting family against family,

brother against brother. Today, a middle-class family doesn’t think twice about

spending tens of thousands of dollars on the newest car or appliance, using a quick, efficient payment plan, and falling into the set jaws of the finance beast.

We fill our garages with junk, and the

Amazon truck loads our porches with boxes of what, we think, will bring us joy.

We elect crooks, both parties, to high office and watch them take millions from unscrupulous

corporations who demand their vote. They pollute the air and place weapons on war onto our streets. We missed the mark. Tent cities

fill the sidewalks under freeway overpasses, and our fellow citizens look to alleviate pain by injesting powerul, deadly synthetic drugs.

I’m glad my mother’s words continue to

ring in my ear, like Shakespeare’s Polonius, when an advertisement begins to

tempt me, I can hear her say, “Mijo, neither a lender nor a borrower be,” and, if that doesn't work, what does is recalling the humiliation of walking to those relatives’ doors and placing a

quarter into each outstretched hand.