“Pop would have wanted you to have it,” said my older

sister as she handed the case to me. “Because you’re the writer in the family,”

she added, though this explanation was quite unnecessary.

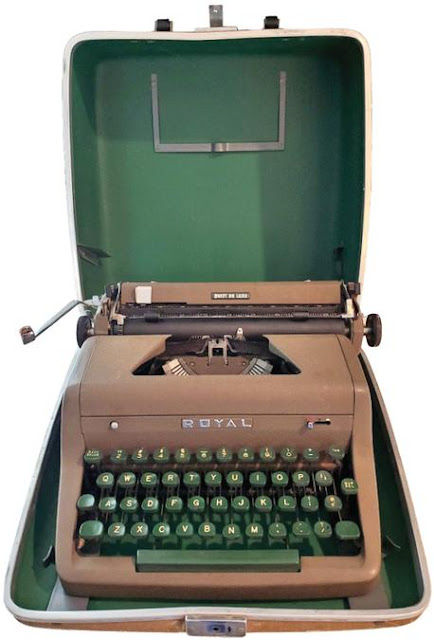

The “it” is a Royal Quiet De Luxe that reportedly was

Ernest Hemingway’s typewriter of choice. The Royal Typewriter Company

manufactured its popular portable model from 1939 until 1959, the year of my

birth. My late father, Michael Augustine Olivas,

purchased it sometime after he had returned to the United States in 1952 after

serving two years as a Marine during the Korean War. I surmise that this

17-pound typewriter was a prized possession for this son of Mexican immigrants

who worked in a factory and had dreams of becoming a published writer.

Sadly, those dreams would remain unfulfilled to the end of

his life in 2020.

As with many immigrant families during the 1950s in my old

neighborhood a few miles west of downtown Los Angeles, my parents were able to

start a family, purchase a small house, and buy a car on the sole salary of my

father’s factory job while my mother focused on the hard work of primary

caregiver to their children, who would eventually number five over the course

of a decade.

My father worked the nightshift at an electric turbine

manufacturing company. He told me that when I was a baby—their third child—he

would set his typewriter near my crib and work on a novel, short stories, and

poetry. Pop joked that all that typing near my young self must have destined me

to the writing life.

I imagine him now, a handsome young man in his late 20s—younger

than my own son—clacking away on that Royal Quiet De Luxe with dreams of

becoming a published writer like the authors he loved: Fitzgerald, Cather,

Maugham, and of course, Hemingway.

Pop’s old portable typewriter is a beast of a machine in

all its mid-century glory. The light-brown metal casing complements the green

keys and space bar. The ivory-colored letters, numbers, and symbols still stand

out brightly against the green beds of the keys, which dip slightly at their

centers to allow fingertips to nestle in comfortably. And the smell—oh, that

smell!—when I open the case: The pungent tang of typewriter ink emanating from

the ribbon ignites a flood of childhood memories. I love that metallic, inky

scent. It reminds me of my father.

What happened to Pop’s typed pages? That was a mystery to

me until about 15 years ago. I had a book reading at Tía Chucha’s Centro

Cultural & Bookstore for a short story collection, and my father attended.

When it came time for audience questions, Pop stood, arms behind his back, and

introduced himself as my father. Everyone nodded, smiled, appreciated that this

man offered his son the support of his presence. Then he said softly, “I used

to write, too.”

The audience again nodded, smiled, and perhaps became a bit

puzzled about where this was going. I grew nervous, not certain what Pop was

planning to say next. He continued: “But it was trite.” I took a breath. And he

added: “Nothing important. Nothing like what you write.”

“I wish I could read

your stories,” I said, not knowing what else to offer.

He waved his right hand slowly to brush away my desires. “I

burned them all,” he said, punctuating the end of his story with a smile that

was far from bitter or morose, just accepting. He then sat, and the room fell

into a thoughtful silence. I could not bring myself to ask why he took such

final action in destroying his creative writing.

But a few years later, when my parents were visiting me and

looking at my various books and literary journals in our family study, I asked

Pop why he had destroyed his pages. As my mother looked on with trepidation, my

father explained that his writing had been rejected repeatedly by publishers,

and he decided that he needed to move on with his life. That meant he focused

on getting his college degree and master’s and eventually getting a job where

he wore a suit to work.

I so dearly wish Pop had saved his writing. I think about

what he wanted to express through fiction and poetry. The question of what he

wrote about was clearly a painful subject for Pop. I tried a few times to find

out what stories and sentiments he tried to tell through the written word, but

he never offered more than a wince and vague responses.

I do know this: My father was a proud Chicano who loved his

culture and people. My suspicion is that the publishing industry in the late

‘50s and early ‘60s was many times less hospitable to Chicano literature than

it is today—even with the structural racism that BIPOC and other

underrepresented writers still face and battle.

And that is a heartbreaking conclusion. A conclusion that

means my father’s voice will remain in my memory and not in the printed word. A

voice that—I believe—would have enriched not only

his family but also the world at large.

[This essay first appeared in The Writer Magazine.]

Daniel Olivas, kudos, you've managed to describe, put onto clear perspective, something that was not meant to exist.

ReplyDeleteMoreover, you inspire me to share this episode.

When I returned from the service I enrolled at Santa Monica College. There,I signed up for a writing class. My first piece "adventure" assignment

described the birth of my son and I received high marks. I thought that writing was going to come easy. The Chicano movement influenced me to write about that, I was certain people would be interested. Boy, was I wrong!

I've always believed that when one of us [i.e., Mexicans] writes from the heart, the product is never trite but speaks to things that have long been repressed, both us as a people, but what we have to say as persons. I can't help but think it would be publishable and eloquent.

ReplyDelete