Primero: Feliz Dia de la Madre! Wishing everyone a lovely Mother's Day. And to Lucha Corpi, mamá de su hijo, Arturo, y tambien de "la página roja," -- gracias por estar con La Bloga hoy!

Born in Jáltipan, Veracruz, México, Lucha Corpi was nineteen when she came to Berkeley, California in 1964. De Mexicana a Chicana, Lucha Corpi has established herself as an important Chicana novelist, poet, essayist, children’s author. She is the author of two collections of poetry: Palabras de mediodía/Noon Words and Variaciones sobre una tempestad/Variations on a Storm (Spanish with English translations by Catherine Rodríguez Nieto), two bilingual children’s books: Where Fireflies Dance/Ahí, donde bailan las luciérnagas and The Triple Banana Split Boy/El niño goloso.

She is also the author of six novels, four of which feature Chicana detective Gloria Damasco: Eulogy for a Brown Angel, Cactus Blood, Black Widow’s Wardrobe, and Death at Solstice. Her new book, Confessions of a Book Burner: Personal Essays and Stories is a departure from fiction and poetry (Arte Publico Press, April 2014). Lucha invites us into her intimate world of life and writing.

Corpi has been the recipient of numerous awards and citations, including a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in poetry, an Oakland Cultural Arts fellowship in fiction, the PEN-Oakland Josephine Miles Award and the Multicultural Publishers Exchange Literary Award for fiction, and two International Latino Book Awards for her mystery fiction. Until 2005, she was a tenured teacher in the Oakland Public Schools Neighborhood Centers.

Amelia Montes:

Gracias for being with us today on La

Bloga, Lucha! Your book, Confessions of a Book Burner: Personal Essays and Stories covers so

many topics about Chicana identity, culture, the creative process, race, immigration,

loss and heartache in a woman’s life.

Had you been writing these pieces for a while? How did the idea of putting these essays and stories

together in one book come about?

Lucha Corpi:

Over the years, I have often sprinkled my readings and presentations

with personal anecdotes. “El cafecito es más sabroso platicadito.” Most

audiences have enjoyed the stories. The essays “Epiphany: The Third Gift,”

“Four, Free and Invisible,” and “La Página Roja” started as childhood and

family oral stories, and I finally wrote them down. I wrote some of the other

stories in essays between the novels in the Gloria Damasco crime fiction

series. After Death at Solstice was

out, I needed a break from writing fiction.

By then, my goal was to write all

these personal and familial stories so my grandchildren, Kiara, Nikolas and

Kamille, would have access to the family history and Mexican culture that had

shaped their father--my son Arturo--their paternal grandfather, and myself.

|

| Lucha Corpi's son, Arturo, and her grandchildren, Kiara, Niko, and Kami |

|

| Lucha Corpi's son Arturo with his wife, Naomi |

As a writer, I

wasn’t satisfied with just the telling of the story. It didn’t provide the

connections to the larger themes in my bicultural world, as an immigrant to the

U.S. It was important for my grandchildren to have that perspective. So

memories and stories wrap around the theme, and the narrative then meanders or

flows steadily through my life in four very distinct communities: my childhood

in my hometown Jáltipan, adolescence in San Luis Potosí, youth in Berkeley,

California and adulthood in Oakland, California. Soon, I had a first draft of

about one-third of the essays. I still didn’t think of this project as a book,

until my good friend and publisher, Nicolás Kanellos and I coincided at a

conference in Toledo, Spain, where he was receiving a Luis Leal Lifetime

Achievement Award, and I was a keynote speaker. My talk was based almost

entirely on the first of the essays in Confessions:

“Remembrance, Poetry and

Storytelling,” with sprinkles from other essays. Nick was interested in seeing

the manuscript. I said it was only a rough first draft of a third of the

manuscript. He said okay. Three months later I sent him the complete

manuscript. And we took it from there.

Two years later,

here is the book, for your pleasure: Confessions of a Book Burner: Personal Essays and Stories.

Amelia Montes: And how very fortunate we all are,

Lucha! In the essay, “Epiphany: The Third

Gift,” you write: “It wasn’t unusual for Mexican fathers, almost regardless of

class, to deny their daughters the advantages of formal schooling on the false

premise that as women they would always be supported and protected by their

husbands, and in the worst case, by their brothers. Besides, even if a woman

learned a profession, she would not be able to make a career of it, because she

would end up staying at home to take care of the family.” Do you feel this is still the case in

Mexico and of immigrant families here in the United States?

Lucha Corpi:

In Mexico, since primary school is compulsory, most boys and girls get

the equivalent of six years of formal schooling. High school is still regarded

as a luxury the majority of large low income families can’t afford for either

girls or boys. It isn’t so much the cost, since it is free. The family counts

on the income the children generate to make ends meet. If the family can afford

a higher education for their children, no question about it, young sons are

given the opportunity first. Girls

who have a primary education have access only to low-paying jobs, and at some

point, they begin to see marriage as a way out of poverty, which, we know well,

isn’t always the answer. Young women in middle-class families have better

opportunities to finish at least high school. More frequently now, parents

encourage their daughters to pursue a higher education degree. And the number

of women with higher degrees has increased. Pursuing a career, however, is

still a constant balancing act for most professional women, even when they can

hire someone to help at home. The overall well-being of their families rests on

their shoulders. Should family needs require it, however, they are expected to

put aside their dreams of a career for a “greater good.”

Immigrant

families in the U.S., even when they have green cards, face problems that seem insurmountable at times, i.e. learning English and navigating a different

cultural system, yet still providing for the family. To start with, the children learn English faster and the

parents rely on them for translation, interpretation of cultural practices, and

guidance. The roles are reversed, and the children, in a way, become the

authority in the family. That alone upsets the Mexican family dynamics with

terrible consequences in some cases. The families that can make this situation

work function as a unit again. For the most part, boys and girls thrive and are

encouraged to do well in high school and seek higher education degrees. There

has been a tremendous increase of young Chicanas gaining admission into

colleges and universities since the 60s and 70s, for sure. And that is always

good news.

Amelia Montes:

In the book, you describe how you skipped first grade, mainly because

you had followed your older brother to school at 4 years of age—and they let

you in! How do you feel now about children who are obviously gifted, and whose

parents might want them to skip grades as your parents had you do? Do you think it’s a good idea? Our school system is obviously very

rigid. How could it change?

Lucha Corpi:

I wasn’t particularly gifted, but it was obvious to the adults around me

that I had developed some coping mechanisms on my own to withstand the rigors

of a structured educational system at that early age and do well. Perhaps I

enjoyed school and excelled because I wasn’t pressured to compete, not even

after I became a “legal” student. I think my parents would not have insisted on

my skipping a grade if I hadn’t been psychologically ready for such a change.

You are right in

pointing out that the public school system is rigid. Its policy of social

promotions based on age rather than scholastic achievement isn’t doing much

good to the individual student. Teachers are caught in the middle of a

conflict, especially because they feel powerless to change the educational

policies made into law by legislators, who have not set foot in an elementary/high

school classroom, let alone as students, for a long time, and have no idea what

classroom instruction and testing truly require. But they make the rules.

Nowadays, some

parents want their child held back to repeat a grade because they feel he or

she isn’t ready for promotion to the next grade. These parents have to do

battle with a public educational system geared toward moving students along to

graduation non-stop. Sometimes, being the oldest student in his or her class

might provide a child with self-assurance, which would then translate into

better academic performance. Conversely, the trend among many middle-and

upper-class parents is to push their children to excel from preschool all the

way to high school. The tots must attend the best preschools where there is

actually a school curriculum that rivals that of a first grader! In many cases,

they are sent home with worksheets that take up their play time and other

extra-curricular activities. These parents focus on gaining a competitive

academic edge for their child, for the time when he or she must compete for

admission into a college or university.

One good thing about these opposite points of view is that people are

talking about these educational trends and, perhaps, this dialogue will bring

about some badly needed changes in the school system.

Amelia Montes:

Your work in Mystery/Crime fiction has been so important to Chicana

literature. You write in “La

Pagina Roja,” . . . “the writing

of crime fiction, when one respects one’s art, is as legitimate as any other

kind of writing; that exposing the machinations of a ‘justice system’ which

more often than not stacks the deck against women, especially women of color .

. . is also a way to obtaining justice for those who won’t or can’t speak for

themselves.” Do you feel that

Chicanas are finally joining you in writing mysteries? Is there more legitimacy today?

Lucha Corpi:

There are many more Chicanas and Latinas writing mysteries or crime

fiction now, including some writers of young adult mystery stories. In the Arte

Público Press anthologies, YOU DON’T HAVE

A CLUE: Latino Mystery Stories for Teens and HIT LIST: The Best of Latino Mystery, edited by Sarah Cortez, who is also one of the writers, there are

eight Chicana and Latina mystery writers, and I know of two more who are now

published mystery novelists. Perhaps some are writing mysteries but haven’t

sought publication of their work. I hope so. Since I wrote “La Página Roja” our

numbers have at least doubled. But the Chicano crime fiction writers still

outnumber us 2 to 1. We Chicanas will catch up. No literary bullets or bullies

can stop us now!!

Amelia Montes:

You talk about migration, immigration, dreams (Morpheus!) and sharing

these dreams with UC Berkeley professor, Norma Alarcón, who helped you see the

importance of your dreams. Are you

still in touch with Dr. Alarcón and with your dreams?

Lucha Corpi:

Norma and I have been very good friends since the eighties. In some

ways, because I was a teacher in the Oakland Public Schools, and not connected

with the—and her—academic world on a daily basis, our friendship grew out of other

interests we have in common. My

first husband was an intellectual, who lived in a world of ideas, and

conversations with him were at times challenging for me. But there were common

threads that made it easier for me to understand his point of view, and for him

to enjoy a fresher, intuitive, but always intelligent perspective from me. I

actually came to enjoy those conversations, as I do my conversations with

Norma. We have never had any trouble discussing topics or exchanging ideas

along those lines. But there is much more that we have in common: literature,

poetry, music, our love for crime fiction, the mantic arts and the world of

dreams, to name a few. We are good traveling companions and we don’t judge each

other. When we talk, mostly on the phone, at least twice a month, we laugh a

lot, especially when we share with one another her dreams and my nightmares.

Amelia Montes: The

cover of the book is also fabulous.

Who is the artist and did you have any say in this cover?

Lucha Corpi:

The cover art is a print titled “The Burning Heart,” by Oakland visual

artist Patricia Rodríguez. She is a fabulous artist, whose art has been

internationally recognized, particularly her mural arts and box ofrendas. But

she has so much more to be recognized for as she has also written essays on

various art topics, published in many literary and academic anthologies.

Patricia and I

met in the early 70s. She was one of the pioneers in the Mujeres Muralistas art movement in the Bay Area and, particularly, in the Mission area of San

Francisco. For a while, the Mujeres Muralistas and Chicana poets used to get

together. We talked about projects, read poetry, checked one another’s works

and, of course, discussed the Chicana movement in many areas of endeavor.

Patricia and I have been good friends since that time, but sometimes to earn a

living she has had to commute to or live in other places for weeks or months at

a time. Right now, she lives in Oakland but is teaching a workshop on mural

arts for young Chicanas in San Juan Bautista, a kind of commitment very close

to her heart. Since she started her career as a muralist and visual artist in

The Mission, she has also been

committed to working with young Chicanas so they may find the creative power in

themselves, and in turn use it as a means and medium to define who and what

they are, to explore their own identities. But San Juan Bautista is a two-hour

commute in good traffic. Because she lives in Oakland, she has to commute

during the week. But since we both live in the same city, I get to see her and

what she’s working on more often. I fell in love with “The Burning Heart” the

moment I saw it. Arte Público usually gets in touch with me for suggestions

about cover art. I usually leave those decisions to them. I’m pretty happy with

their choices. But this time I immediately thought about “The Burning Heart.” I

sent the image to Nick Kanellos, together with other images of hearts among

Patricia’s works. Nick chose “The Burning Heart” as well. I love my book, and I

thank Patricia for the gift of her art and her friendship!

Amelia Montes: In the essay, “Colorlines,” you tell us a humorous story which involves the actor, Edward James Olmos, and yet it also weaves in a very

interesting narrative regarding skin color. In our Chicana and Chicano community (and this also happens

in the African American community) we still struggle with skin color, whether

someone is “guera” or “morena.”

Your piece is like a mini “coming of age” regarding the acceptance of

what you look like. Do you think

this is still a problem? What can

individuals and communities do to help children grow up to love their skin color,

whatever it happens to be—and not judge others?

Lucha Corpi:

As I wrote in the first essay in the collection, colors are among the

earliest memories we humans have, and in some very odd ways, at times, they

determine our predilections; at others, they feed our subliminal fears; quite

often, they determine or dictate our biases. Since we rely so much on our eyes

for survival at night, for example, when we feel the most vulnerable, the

colors associated with night—the skins of darkness, so to speak—often trigger

in most of us the instinct for survival. Transfer that to a social or school culture

that emphasizes the importance of a lighter color of skin over a darker one, or

the other way around, and our children find themselves in a racial mire without

the tools and materials to wade out of it. But it is not up to the children to

find a way out. Most children in a playground tend to get along, unless there

are issues of over-aggressiveness on the part of one group or another. I always

remember my father’s lessons: The education of a child begins with the

education of the parents, in particular the mother. We must take the initiative

to have these kinds of conversations among the adults and to overcome our fears

by exploring them in ourselves first. I’m glad I mustered up the courage to

write the “Colorlines” essay.

Amelia Montes:

Yes, skin color is a subject that has been and continues to be so

important to our gente. Is there something else you’d like to say about the

“Colorlines” section (or if you want to say that you still hope Edward James

Olmos will read your books AND send you a kiss!) Orale!

Lucha Corpi:

You’re making me laugh, querida Amelia! Gracias! But no, I have no

expectations of being kissed (on the cheek, of course) via either letter, on

the phone, by e-mail, Facebook message, or Twitter tweet, or in person. No

expectations along any lines, color or literary! Maybe he’ll find out about Confessions and read the essay. I hope

his ego can hold up as he realizes that my inquiry has more to do with how I

viewed myself before and after the incident. His behavior facilitated a conversation

with myself about color that was long overdue. Tan Tan!!

Amelia Montes: Do you still travel often to Mexico and

do you also write there or do you keep to the writing of your work in the U.S.?

Lucha Corpi:

I travel to Mexico as often as I can. I enjoy the company of my brothers

and my sister, and their families. I usually do a lot of reading, in Spanish,

in Mexico, and only jot down lines of poetry or reflections from time to time

on a small notebook I always have with me. I own only a flip cell phone, which

I carry with me only when I’m out of the house, mostly for emergencies. I don’t

own a laptop, a smart phone or tablet. When I travel anywhere, I want to enjoy

the place, the people, smell the aromas and taste the food, have a sense of

place as I blend as much as I can into the environment. I am addicted to

writing now. If I have a computer or tablet with me, I’ll find myself most of

the time in my hotel room pounding the keys. I’m idiosyncratic that way.

|

| Lucha Corpi and her husband, Carlos Medina Gonzales |

Amelia Montes:

What is your writing schedule like? For example: do

you write every morning? There’s a

section in the book where you recount a difficult period (the divorce) and you

were writing a poem a day. You

wrote that writing a poem every day saved you. Please tell us more about this.

Lucha Corpi:

When I was a full time teacher, the only time I had the peace of mind

and quiet to write was from 5 to 7 a.m. In truth, that was the only time I

could write because I was at work from 8:15 a.m. to 5 or 6 p.m. Now that I’m

retired, I don’t have to get up at 5 a.m. to write. But if I’m working on a

short story or a novel I still do it early in the morning. However, each kind of writing has its

own particular time. For example, I tried writing personal essays or poetry in

the morning and it just didn’t feel right. I produced little and kept finding

excuses to walk upstairs, have coffee, and work on a crossword puzzle. The best

time for me to write poetry is near midnight, and I love listening to

instrumental music then. The best time for me to write a personal essay is

early evening and I must listen to jazz. Why? I’m idiosyncratic that way! One

thing is a constant, though. Whether I produce or not, I sit down to write

every day.

Amelia Montes:

Muchisimas gracias for taking time with La Bloga, Lucha We are wishing you much success with Confessions of a Book Burner: Personal Essays and Stories.

Lucha Corpi: It’s

been my pleasure, querida Amelia. Mil gracias. Dear La Bloga readers, I can

promise you only one thing: If you decide to get and read Confessions of a Book Burner: Personal Essays and Stories, you won’t be bored! Gracias, y abrazos

calurosos a todos y todas.

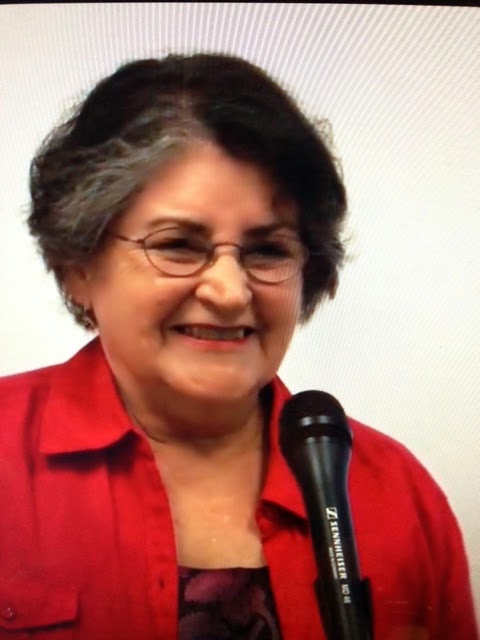

|

| Lucha Corpi speaking to UCLA students in the Chicano Research Center, June 4, 2013 |

wonderfully informative and personal interview with one of my favorite writers. the familia fotos add a warm note on this mothers day. happy mothers day lucha!

ReplyDeletemvs

Gracias, Michael. Amelia--Professor Montes gave me some very good complex questions, and I simply had to live up to them--the trademark of a good teacher. See you on Facebook, dear Michael. Abrazo.

ReplyDeleteLC

Gracias Amelia and Lucha. Great interview. I first read Lucha Corpi in college when I was 18. She was one of the first Chicanas I ever read and it was so empowering. Looking forward to reading Confessions of a Book Burner. Love the pictures of Corpi at the end of the blog. She looks radiant, dynamic, and llena de buena-vibra. Felicidades Lucha, y feliz Día de Las Madres.

ReplyDeleteGracias, Olga, for your comment and for your support, which made my Mother's Day more enjoyable. Besitos.

ReplyDeleteLC