Michael Sedano

What’s that Japanese word for book-hoarding? How many to-be-read stacks of books do you have, or is it one wobbly stack?

Many of us cherish thoughts of tackling a book we’ve held-off reading owing to lack of time, que no? Reading Cervantes, or doing Quixote in Castellano? Or simply reading more literature in Spanish--like the facing page edition of Caras Viejas Y Vino Nuevo (link), so you can read both languages at the same time!

Here's a suggestion: Read experimentally, give yourself a break and do something different. Read the Norton Anthology of Latino Literature cover-to-cover. A bit of Bocaccio, a chortle at Chaucer. This plague has unknown duration but for sure, there’s going to be lots of time to do cool stuff instead of worrying.

Time is made for reading. If it hadn't been around already, people would have had to invent time so they could make some time to read. Time is life's most precious commodity.

During my early working life, I pulled the graveyard shift at every opportunity, relishing those overnight hours of reading. I had one job at Kaiser Steel whose duties required waiting a full 7 and a half hours for a bunch of steel coils to cool enough to run a micrometer on an edge. The foreman told me, “don’t let me catch you reading.” He never did.

On the world’s highest anti-aircraft missile site, overnight duty found me one of two soldiers awake all night. My sole responsibilities on that mountaintop were making hourly commo checks and not sleeping. No one attacked us and killed us, so I read a lot of books instead.

Today, while I wait around for this plague to kill me, I intend to use time like I always have, gardening, playing piano, cooking, and caring for my wife, and reading like it’s going out of style. So many books, so little time.

How about some non-fiction?

Writing/Righting History. Twenty-Five Years of Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage (link) brings 500 pages of scholarship recognizing the quarter century of work conducted by numerous people to recover historical documents and literary works produced by raza in United States history.

Fifty-some years ago, or almost, I came across a Chicano Literature anthology edited by Antonia Castañeda, Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, and Joseph Sommers. That collection, Literatura Chicana: texto y contexto, was among the best of a stellar collection of Chicano Literature anthologies produced in the 1970s and 80s. Now, Castañeda brings another historic anthology and it’s perfect for reading in plague time: It’s long.

You will want to focus when you read these essays, in fact, like all competent scholarship, reading your way into Writing/Righting History promises to take your mind off anything else as your mind wraps itself around tightly-constructed intellectual elegance, typified by these opening words in the Preface by the University of New Mexico’s A. Gabriel Meléndez:

“Over the past two decades the Recovery Program’s work has been to unearth early Latino/a writings and to critically reassemble these writings as the foundational epistemology documenting the experience of generations of Latinos living in the United States and to give proof of the many ways in which each generation has determined and shaped the political and cultural life of the nation.”

Arte Publico Press has provided the institutional heartbeat of this 25-year project, sponsoring academic conferences, collecting proceedings, and publishing them as its raison d’etre. The current title arrives with two books under the same cover. The first book-in-a-book, Considering Recovery’s First 25 Years: Reflections and Testimonios, collects scholarly accounts of the recovery project’s quarter-century of defining objectives and producing accomplishments. The second book-in-a-book offers a fascinating collection of academic investigations presented at a recent conference. This is, Recovering The US Hispanic Literary Heritage, Volume X.

The diversity of subjects explored inform an understanding that Latina Latino literatures grow from Spanish, English, and Sephardic communities. Scholars delve into immigration, colonialism, human geography, exile. Ethno-nationalistic concerns shape the book into divisions focused on Mexican California and New Mexico personages, in Parts 1 and 2, and essays born of Cuban exile, in Part 3. Part 4 of Volume X introduces/recovers journalist Jorge Ainslie.

“Jorge Ainslie is a prime example of a writer totally immersed in the political unconscious of his generation, and as such, his writings underscore an underappreciated feature of the Spanish-language press in the United States: its role as translator and its varied acts of translation.”

The Recovery project may be less familiar to many readers of Chicana Chicano Literature and other raza literatures, whose interests gravitate to fiction and television. Then again, this may reflect certain origins of the project dating back to the creation of Chicana Chicano Literature in 1969.

The first book titled “Chicano Literature” did so pointedly. It was the 1969 edition of Octavio Romano and Herminio Rios' El Espejo:The Mirror, whose first printing carried the subtitle “Mexican-American.” The publisher, Tonatiuh Quinto Sol rode high as a cultural leader in the 1970s. TQS introduced Bless Me, Ultima, and sponsoring writers like Tomas Rivera and Anaya, José Montoya and Alurista, TQS was polishing a Mexican-centric definition of “Chicano Literature.”

Enter Juan Bruce-Novoa’s essay, Canonical and Non-Canonical Text. Raza literature is more than Mexicans and Chicanos, the non-canonical stance argued, with brilliant rebuttals in the form of writing by Puerto Ricans and other gente. Revista Chicana-Riqueña was the East Coast’s answer to Berkeley’s El Grito journal, followed by a succession of journals subsequent to El Grito's demise. Readers find exemplars of this non-canonical approach in the anthology Floating Borderlands: Twenty-Five Years of U.S. Hispanic Literature.

The canonical-non-canonical pedo was the best thing to happen to United States literature; it birthed the field of Chicana Chicano Literary Criticism. And I mean that in a non-canonical way, raza.

Back in 1633, rudimentary forms of governing emerged among Europeans arriving along the Atlantic coast, in ever-greater numbers from war-torn Europe. On the Euro mainland, endless war and another bubonic plague inspired the isolated village of Oberammergau to strike a bargain with their Bavarian gods: they’d put on a play if the plague would stop. It stopped and they put on the play, and have, every ten years. Today’s novel coronavirus plague may cancel it unless they can strike a new bargain. In Mexico, different Europeans were securing the chains of colonialism onto indigenous populations. One result of the latter—bear with me here—is the Hispanic literary heritage. Hence, what an appropriate non-fiction book to read during plague time. Make a bargain with yourself, if you agree to isolate yourself and read adventurously, you’ll remain in good health. Here’s to safe reading in plague time.

More Non-fiction from Arte Publico.

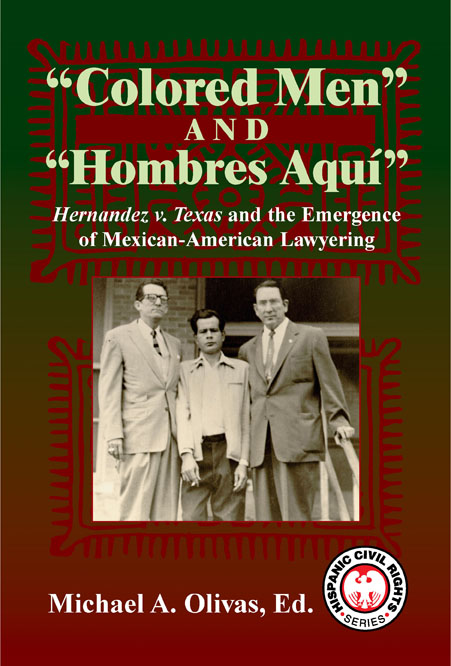

Heavy duty reading comes from a law school-worthy textbook, "Colored Men" and "Hombres Aquí” Hernandez v. Texas and the Emergence of Mexican-American Lawyering.

From Arte Publico’s Hispanic Civil Rights series. Back cover blurb:

“this landmark case, the first tried by Mexican-American lawyers before the U.S. Supreme Court, held that Mexican Americans were a discrete group for purposes of applying Equal Protection.”

And Some Creative Non-fiction for Young Adults from Arte Publico.

“I Alone” Bernardo de Gálvez’s American Revolution. Author Eduardo Garrigues is a novelist and applies the technique to imagined conversations. Here, for example, Gálvez confronts a resentful subordinate by comparing hard luck stories:

“I assure you that many winters when the bacon preserved in lard and goat jerky ran out, as a child I had to stuff myself with prickly pears to assuage my hunger pangs.”

Garrigues’ narrative reads like a product of professional historian research, but such conversations are the stuff dreams are made on, and stuff that gives this book interest beyond its account of whom the back cover says, “One of the unsung heroes of the American revolution was Bernardo de Gálvez, governor of Spanish Louisiana and leader of armadas against the British in North America. He took out one red coat Fort after another, culminating with the defeat of what was thought to be the impenetrable British forts at Pensacola.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you! Comments on last week's posts are Moderated.