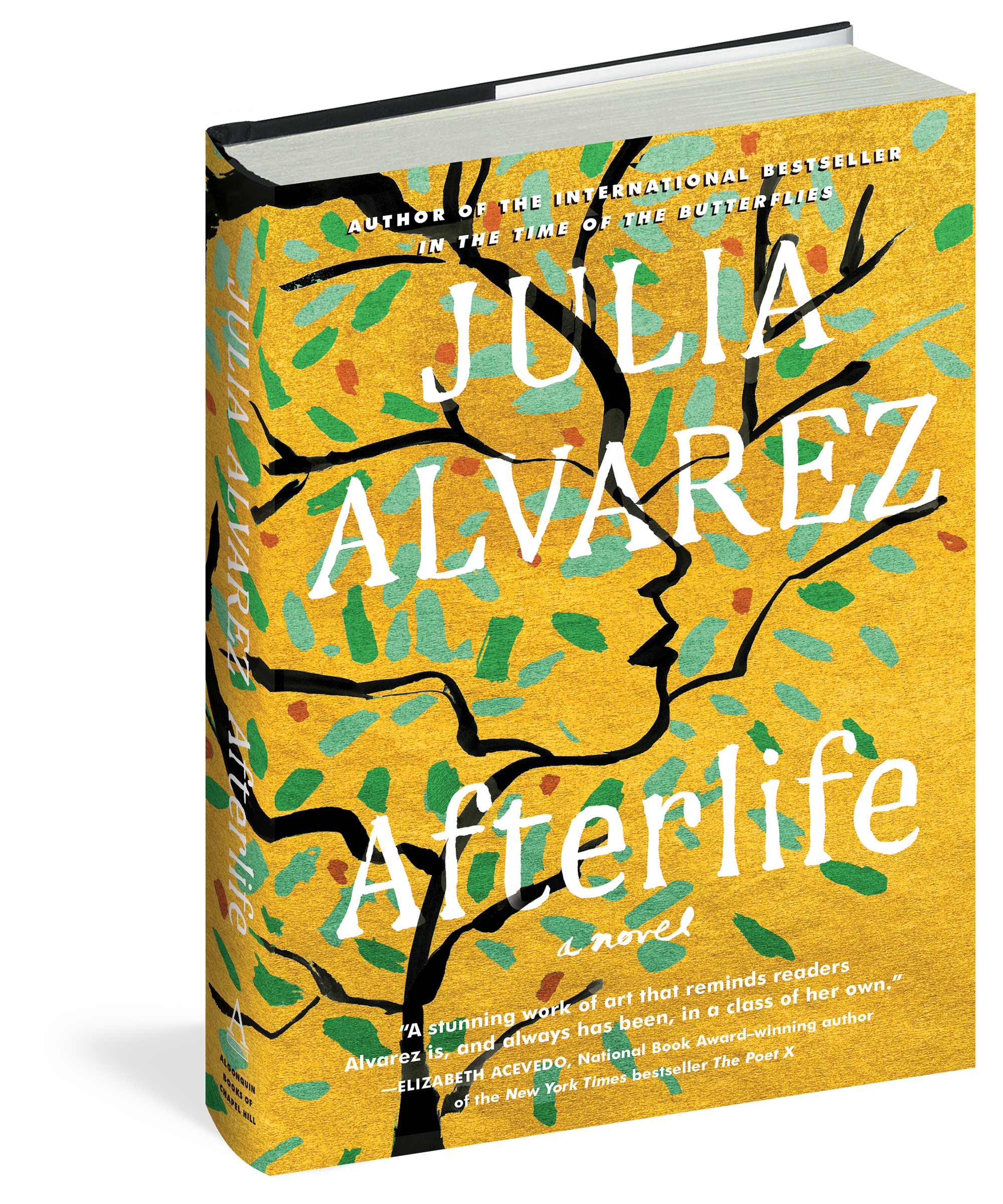

Review: Julia Alvarez. Afterlife. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2020. IBSN 9781643750255

Michael Sedano

The title of Julia Alvarez’ new novel, Afterlife, gives paranomasia a good name. Puns, it’s been said, are the lowest form of humor. Thing is, Afterlife, the novel, isn’t funny. Far from “low,” the novel’s themes touch on essential humanity—death, grieving, mental health, kindness, ethnicity--all don’t stray far from the heart side of a heart-mind dichotomy. That's the high road in my book.

Antonia and her three sisters make a powerful sisterhood of Dominicana mujeres. Izzy and Antonia the elders, Tilly and Mona the younger. Age, in this family of women, always makes a difference, but it’s a dynamic the four accomplished professional women exercise often to put a sister on edge or gain a sisterly upper hand. Alvarez, and the sisters, make Antonia the family leader because of her age and disability of the oldest sister. The sisters defer also to the second-oldest because she only recently became Sam’s widow.

Elements of Afterlife offer charm, other elements deadly seriousness. Charming are the ethnic references and most of the sisterhood intimacies. Each sibling operates within her own world pushing and pulling herself into the sisters’ orbits. The relationships are marked by loving bickering and cruel-cute nicknames, often played for funny and funny-ish, like who gets what ring-tone. It’s all funny until Izzy goes missing. Poor Izzy, her mental deterioration becomes the stuff of reductio ad absurdum, the kind you don’t know to laugh or cry. You cry.

Mental health and death hit the sisterhood, introducing two related forms of grieving. Antonia has her mind to pull her through the grief of Sam’s death. The character speaks of a hole that needs to be filled with memories. It’s her way to keep alive the man, not just his memory. She invests sentiment in things Sam made or held in his hands. She seeks his afterlife counsel as the family decision-maker, the “good cop” to Antonia’s “bad cop.” In filling the holes, Antonia begins losing sight of herself. “Be yourself, everyone else is taken,” gives the character a chuckle, but it’s not funny. The reader wonders, can Antonia escape Sam and be herself? As the novel progresses, Antonia is pulled increasingly apart by grief, after Sam, after Izzy abandons stability.

Alvarez doesn’t offer any easy consolation to gente suffering grief, but it’s a book for them.

Antonia first goes to Matthew Arnold, finding momentary solace but insufficient. The profe has a deep repertoire of poems in her head, and pithy sayings on her refrigerator. The widow with a research degree delves into the literature of grief to find key thoughts. “Remember to take care of the caretaker,” and “You’re entitled to a little TLC yourself.” “Entitled” hits her wrong.

Readers may find Antonia is too hard on herself. What privilege do I deserve? She asks herself, working out the overwhelming feelings that heap on a mourning person. “Why me?” she asks herself, finding no answer but a pointed question from imagined Sam. “And what good does that do anyone? She imagines Sam dismissing her easy exonerations. And maybe that is how he will keep coming back: periodically breaking through the firewalls of her narrow path with his insights, suggestions, questions.”

Death fills one niche of Antonia’s world. Her sister’s mental deterioration a second, a pair of immigrants a third. Readers experiencing mental illness may gain some insight into their own situation in the way Alvarez’ characters deal with Izzy’s health. Families need to deal with issues like residential care—it’s really expensive and these 4 women can handle the weight—and the sometimes eccentric-appearing behaviors. Izzy buys a herd of Llamas, for example, and goes missing for weeks driving the sisters frantic and they hire a costly pair of private investigators.

Izzy is a tragic character whose headlong trajectory to ruin places enormous pressures on the sisterhood. The reader sits on edge at the worst-case prospects facing the wandering Izzy, and the frantic maneuvering by the panicky sisters thinking worst-case scenarios.

Antonia doesn’t allow herself to be overwhelmed in the sisterly intervention for the broken Izzy, because at the same time, Antonia’s gotten herself into incredibly troublesome territory back at home in the form of a pregnant undocumented teenager and a resentful macho. It’s a ridiculous predicament but Alvarez won’t let you laugh.

This plot turn hits the reader as painfully obvious from the early pages. The story exemplifies a character’s judgment weakened by grief. As the “bad cop” in the marriage, Antonia would have resisted helping the laborer bring his girlfriend to Vermont, then housing the pregnant teen while providing concierge services. Overcome by grief Antonia yields to heart-not-head decision-making, “good cop.”

Sam is in her head, it’s her way to keep him alive, to a point she assumes his “good cop” role and in the process is losing control of her immediate surroundings and her need to separate herself from Sam’s quiet dominance after life. Her problem—Alvarez doesn’t let Antonia know it—is Sam’s a memory for everyone in town, but unlike Antonia, the memories don’t fill any holes. The town has already let Sam go. Antonia benefits from the residue of Sam’s presence, but they’ve moved along, let Sam go except as a storytelling ritual.

For so abbreviated a novel—only 256 pages—Afterlife fills itself with big issues. A complexity of interwoven themes finds elegant expression in characterization and plotting. Writers will marvel at an economy of style and efficiency that plants words and ideas early in a plot then bursts forth with the idea when it’s most useful or to offer some surprise.

The Sheriff, for example, offers pleasant surprise. The community feels tense from anti-immigrant feelings and ICE; even local law enforcement will be dangerous to gente sin papeles here in Vermont. The Sheriff has a hulking figure, one might think of a guy named Bull or Rock. When the lawman tells Antonia he’s on his way to “the Mexican place” a frisson of worry ignites, is he going to bust Lulu?

The badge likes Lulu’s food. The man displays kindness of the best kind when he tips off Antonia that ICE is planning a raid, then he pulls her and the two immigrants out of serious hot water, maybe owing to something Sam did, maybe he’s sweet on Antonia. Kindness, however, comes from places you don’t expect. Alvarez is not into sad endings.

Antonia concerns herself with what Sam called her “othering,” or imposing Antonia’s values and ways upon other people’s. A remedy to “othering” is taking people at face value and being kind, seeing to their immediate presence and needs. Like in Greek drama, the literature profe thinks, welcome the guest, see to her needs, then get the chisme.

That humble field worker with the “Doñita” and hand-kissing lies his ass off to Antonia. And he hits her up for a loan to pay off coyotes to greyhound his ransomed girlfriend from across the country. When Antonia finds the girlfriend taking residence in her garage, she lets her move in. The girl’s pregnant, at 17, and it’s been two years since Estela and Mario have seen one another.

Alvarez’ immigrant theme centers around this pair of liars. Antonia’s determination not to “other” them (nor the slyly courting Sheriff), not only spares the immigrants Antonia’s dudgeon, she plays matchmaker to wrap happily ever after for right now the Estela-Mario plot. The kids are happy, the baby’s got a smart mom and a step-dad growing affectionate, and they went back where they came from. If you’re concerned with the lies, money, and expenses Antonia went through over those two kids, you’re othering. They did what they had to, they must have been entitled to that TLC.

So many broken things that need to be put together fill Afterlife. Antonia’s broken heart, broken life, broken wholeness has her bouncing from sister to sister, expense to expense, error to error, or is that kindness and humanitarianism she's doing? Find a poet, or find a chestnut to help explain the feeling. Antonia the literature professor turns up her nose at those pithy sayings and the sisters the same to the poetry. But Antonia has unspoken belief in those chestnuts. That's what English Profe Antonia would call Apophasis and share a memory about a class on rhetorical tropes that reminds her of Sam.

Afterlife is a title, a pun, and more than anything, a consejo. Antonia has to make sense of life after Sam’s life. Dealing with that complex of feelings, Antonia’s sister disappears and the world turns chaotic. Disabled people need caretakers, a kind of afterlife, too. Broken things need not stay broken, the book concludes. There’s this Japanese technique Antonia learns, mending a broken plate together with gold-infused glue. The thing takes on a new life, the fractures not made invisible but emphasized, this is what comes new with care and attention, after life.

Link to publisher's website with info by the author.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you! Comments on last week's posts are Moderated.