|

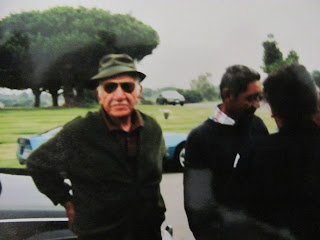

| Mike Rios Escarcega, always ready to run |

Back in the day, the word in the West Los Angeles neighborhood was wherever Mike travelled to compete in high school track events throughout L.A., he could keep up with the best of them, if not beat them, until he made it to the L.A. High School City Championships, held at the famed Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, built for the 1932 Olympics, and home to Rams, Raiders, USC and UCLA football, before the Bruins moved on the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, a place the old-money folks like to call the Arroyo Grande.

For Mike, representing a little-known barrio on L.A.'s westside, the race was a big deal. All his family and friends would make the hour-long drive to Vermont and Exposition to watch. The top runners from all of Los Angeles schools would be competing, and Mike was one of the favored to win, or at least keep it close, according to barrio lore. But rumors from the same Westside barrios, over the years, said -- that’s not how it turned out, not even close, one of those weird hometown stories you hear, from time to time, and some folks still asking: where was Mike on the final turn?

Before my uncle passed on to the great hunting grounds (no joke, Mike was an avid hunter and all- around outdoorsman), I got a chance to talk to him and asked if he competed in the Coliseum, like everybody said, and what really happened that day.

He started with a chuckle, and his favorite expression, “Oh, Christ,” then went on to tell the tale, but first, he had to set it up with a little backstory.

“I played football at University High School. Then I started to play baseball." He laughed. "But baseball…no, no, no.” He made a face as if playing baseball was like facing a firing squad. “I didn't like the way the ball went by my head when I batted. No, I just didn't like the way it went peee-shhooooo right past my head. I said, no, the hell with that shit. Forget about it.”

He leaned back in his Lazy Boy and began recalling the past. "So, I started running track, you know, and I made the B team. I was pretty good. They moved me to the varsity. I was okay.” He was being modest. Word throughout the neighborhood, the way the old-timers told it, he was more than ‘okay’. He was one of the best.

“Yeah, I went to the Coliseum for the City Championships, something like 1935 or ‘36, and ran -- the 1320,” about a lap short of a mile. “I guess I was pretty good. I was just a teenager, and I even got into the Aguila Real, the Royal Eagles track club, all Chicanos, older guys, you know."

The way he said Chicanos, purely for a collective, ethnic identification, used like other men of his generation, nothing political about it. "The club started, oh, I don't know, in the 1930s, around there, some time. We travelled all over L.A. and San Fernando to race other clubs.” He nodded, happy with himself, like he’d forgotten his accomplishment.

“Anyway, I was supposed to be getting ready to race at the Coliseum, and I should have been training, but I missed school for a couple of weeks, so I couldn’t train.”

What he didn’t say was these were the Depression years. His family had little money, like many of the families in town, but he did admit, “I missed school because I had to work in the fields, picking beans.”

On L.A. westside, in the 1930s, there were still many ranches and farms throughout the towns, and the growers always needed workers. Often, high school kids met the call, if they weren’t caddying for golfers at the Riviera Country Club or up at the Cheviot Hills Golf Course. When there was no work and no money, the parents would send the kids to line up in the alley outside a neighborhood theater, the Tivoli, where the government agency, the WPA, handed out bags of vegetables, so Mike was lucky to find work, even for a couple of weeks.

“In the Coliseum, I knew it would be in front of the whole city, a few thousand people. When I finally made it to school to workout, one day, my muscles tightened up. I could hardly run. My coach said what the hell’s wrong. I didn’t want to tell him I was in the fields working. Man, he balled the hell out of me…Coach Betts. I think he just died, not too long ago. Ask your dad about Coach Betts. All the guys knew him -- tough. The coach told me, 'See what you did! You shouldn’t miss school. You needed to be out there training,’ and on and on, and all that….”

In those days, a lot of kids, high school age, left school to work at whatever they could find. Leaving school by the eleventh or twelfth grade wasn’t uncommon. Some were lucky enough to have stayed in school that long. When the war came in 1940, quite a few joined, thinking it was a good way to earn money to send home to the family. If they volunteered for airborne, they’d get an extra $55.00 a month, quite a sum in 1940. So, a bunch of Chicanos became paratroopers.

"Comes Saturday and we're at the Coliseum to race,” he said, sitting back in his chair, like he was right back in the Coliseum. “I don't know, I was all right, feeling good, warming up, taking practice laps, all that. When the race started, I kept up. I ran hard, stayed in the pack for most of it, but then we came down to the home stretch, nearly the end, and I kick, but…forget about it," he let out a chuckle, and said, "Oh, man, my legs tightened up, and the runners passed me, one guy after the other. And then the last guy ran past me, left me in the dust.”

I interrupted, “But they said nobody knew what happened to you. You weren’t in the group.”

He laughed, “Yeah, well, you know where you enter the Coliseum, right, the tunnel?”

Of course, I knew. The world’s finest athletes had come through that grand entrance. The great runner, J.C. Owens, UCLA’s football star Jackie Robinson, the Ram’s Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hersh, Norm Van Brocklin, Bob Waterfield, Rosie Grier, UCLA’s All-American tailback Primo Villanueva, USC’s All-American linemen, the McKeever brothers, the Raider Lyle Alzado, and so many more. The tunnel was legendary. Even as fans, when you look at the tunnel, huge, dark, before any event, it’s like expecting the Roman legions to come marching out.

“Well, hell,” he said, remembering, like the image had never left him, “I knew I couldn’t catch them. My legs were cramping, so I just ran in there, into the tunnel, and I stayed there where, I thought, nobody could see me.”

“So, it was true. You didn’t finish the race?”

“Everybody from Sawtelle and Santa Monica came to see me race that day, my mom, your grandma, Santos, my Aunt Saturnina, my brothers, Peanuts and Roy, my sisters Vera and Elia, your dad, Dario Sanchez, Freddie Santana, all our friends, hell, everybody came to watch me race.”

He looked sad for a second, like he was really back there inside the tunnel, hiding out. Then he broke out into a laugh, like it wasn’t anything he needed to worry about anymore, like it really was an old joke. “Oh Christ, they were all looking for me, you know, to come down the stretch, to catch up, and win. When they didn’t see me anywhere, they were, like, wondering what happened to me. I wasn’t with the pack when they crossed the finish line. Nobody knew where I was. Man, I was in the tunnel, hiding."

He shook his head. “I couldn't even walk. My legs cramped up on me. You know how you get cramps? Christ, one little shorty-guy, he must a been…hell, I don't know, maybe four-feet tall, when he goes by smiles and waves, like telling me to come out and finish. I was, man, forget about it. I couldn’t even walk.

"

He shook his head. "Afterwards my aunt asked me, 'Pues donde estabas hijo?'

“Oh, man. I was so embarrassed, but I told them, 'Pues estaba metido alli, tia,' and I pointed to the tunnel.”

Daniel Cano’s 2010 novel, Death and the American Dream, won first place, best historical fiction at the International Latino Book Awards.

3 comments:

Another good story, I enjoyed the read, thank you .

Another great story indeed. Keep them coming Danny. I love reading about the days of long ago. So nostalgic. Thank You!

Thanks for leaving a comment. It lets us know there really are readers at the other end.

Post a Comment