The world's longest-established Chicana Chicano, Latina Latino literary blog.

Friday, February 28, 2020

Notes from the Past

I looked over old writing notebooks and surprised myself. "Who wrote this stuff?" I asked no one in particular. The torn and creased journals were decades old and so they offered clues about who I once was or who I might have been or who I missed completely. Without any comment, here are a few pages from those notebooks. Non-poems from a non-poet. Copyright 2020 Manuel Ramos.

_______________________________

White ball of webbing

in the corner

of the wall,

trapping meager lives

before they know better.

It was too damn hot

but it had been weeks

since she cleaned the house.

She broke away the web

with her hand

wiped it with an oily rag

made that corner shine

until she saw his eyebrows arch

just before he laughed

at the silliest thing she could say.

The rag was no help

couldn't clean the flashes

hidden in each room

the smells

the way his face wrinkled

when he saw her.

The evening breeze through the open window

pushed the rag off the table

where she sat

trying to remember what she was doing.

_____________________________________

I tossed her in Lake Michigan,

left her stranded at the Blues,

drunk and disorderly.

Found my sanity

under the grungy seat

of the train slashing through the South Side.

Regained a bit of confidence

on Clark Avenue,

among the bars, comic books and groceries.

The Holy Spirit and New Age mush and

her mother and a piece of ice

moved into my space in her heart.

And I moved on.

__________________________________________

4 men fidgeted

3 black, 1 brown

number 5 on trial

a minor offense

crucial to survival

of systems, methods

obscure levels separated by lines of power.

Able to say only so much

not enough to stop it.

Aliens to the process

impossible to learn

birth right essential

what could 4 men

3 black, 1 brown

offer without

a system

method or obscure level

of their own?

They lost number 5.

________________________________________

Aztec poetry -- contrast Quetz. and Huiz.

"Lady of the Skirt of Snakes."

________________________________________

MURDER AT THE TEATRO

Jose is killed - shot by a late night visitor to the teatro--

no one else around --

all others appear to have good alibis but Det. Vigil

finds out that none have very good alibis --

all those who could have done the killing had motives --

Vigil: distinguished, cynical, tall,

recognizes the ambiguity (contradiction)

of being a Chicano cop.

Ricky: Mad Mex - political motive

Maria: jealousy over leaving the teatro

Roberto: city guy?

person on the phone?

Isabel: unrequited love?

Later.

______________________________________

Manuel Ramos writes crime fiction. His latest is The Golden Havana Night (Arte Público Press.)

Thursday, February 27, 2020

Chicanonautica: American Monsters, Dirt, and Other Chingaderas

by

Ernest Hogan

The

lizard on the ceiling is still watching over me. Or maybe I’m

hallucinating. Those fumes at work yesterday because of the

remodeling were something.

I’m

tempted to do a stream-of-consciousness rant about the latest

developments in the election, and the new literary movement that

spoinked out of American

Dirt pendejada

when it’s just the media finally noticing Latinoid writers like we

just snuck across the border while in reality we’ve been around for

a long time and they just haven’t been seeing us . . .

The

lizard moved again. It’s not hibernating. Just moving really slow.

And

there are other things, good things happening.

Like

my contributor’s copy of American Monsters Part Two (Part

One being about South America) making its way from Merry Olde England

to Wild and Wooly Arizona.

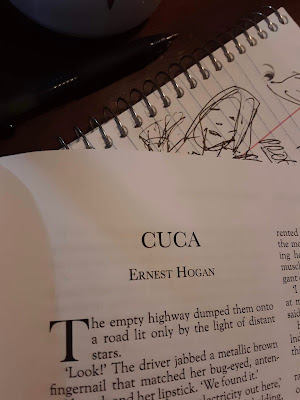

My

story, “Cuca” about a luchadora, the monsters of Aztlán, and

21st century culture come together in the sixth volume of a series of

coffee table books from Fox Spirit Books about monsters from all over

this crazy planet. Chicano fiction crashes a global monster bash!

In

a gorgeous book with classy illustrations, it will jazz up your

coffee table and show your guests that you're hip to monsters.

Ya

gotta know your monsters. Especially when a lot of them are running

for office.

Ernest Hogan is not just a Chicano cyberpunk.¡Viva Myriam Gurba!

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

WHEN JULIA DANCED BOMBA / CUANDO JULIA BAILABA BOMBA

By Raquel M. Ortiz

Illustrations by Flor de Vita

ISBN: 978-1-55885-886-2

Publication Date: October 31, 2019

Format: Hardcover

Trim: 8.5″ x 11″

Pages: 32

Imprint: Piñata Books

Ages: 6-9

This bilingual picture book introduces

children to an Afro-Latino musical tradition.

“Julia, they’re already warming up.

Hurry!” Cheito says to his little sister as they rush to their bomba class.

Cheito is a natural on the drums, but Julia isn’t as enthusiastic about

dancing.

Julia tries to imitate the best dancer in

the class, but her turns are still too slow, her steps too big. She just can’t

do anything right! When the instructor announces the younger students will be

participating in the bombazo and performing a solo, Julia is terrified. When

it’s her turn, she takes a deep breath, closes her eyes and focuses on the beat

of the drum. As she dances, Julia notices that the drums are actually talking

to her. Feeling braver, she stops worrying and trying so hard. Instead, she

loses herself in the rhythm of the bomba drums and enjoys herself!

Introducing children—and adults!—to the

Afro-Latino tradition of bomba music and dancing, author and educator Raquel M.

Ortiz shares another story for children ages 5-9 about her rich Puerto Rican

heritage. With lively illustrations by Flor de Vita that aptly express Julia’s

frustration, fear and joy, this book will help children understand that

practicing—whether dance steps, dribbling a ball or playing a musical

instrument—yields results!

A Junior Library Guild Selection

“Afro-Puerto Rican dance traditions are

celebrated through one girl’s breakthrough moment with bomba. A solid reminder

of music’s power and a good primer on Puerto Rican dance culture.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“The theme of dance as a liberating force

for self-expression is enhanced by cultural context in this picture book.

Ortiz’s straightforward text taps into several relatable and authentic themes,

including the pressure children can feel to embody all aspects of their

cultural backgrounds, and dispelling the notion that all Latinxs are naturally

rhythmically gifted. A wonderful pairing for titles depicting the

intersectionality of Latinx heritage, like Margarita Engle’s Drum Dream Girl

and Eric Velasquez’s Looking for Bongo.” —Booklist

“The illustrations provide readers with a

clear view of Julia’s emotions as she confronts her fears and anxiety about

dancing. The author includes general information about the bomba as well as a

glossary of Spanish words in this bilingual edition. VERDICT An additional

purchase for patrons who are interested in learning about bomba, a Puerto Rican

dance.”—School Library Journal

RAQUEL M. ORTIZ was born and raised in

Lorain, Ohio. She is the author of two other bilingual picture books: Sofi and

the Magic, Musical Mural / Sofi y el mágico mural musical (Arte Público Press,

2015) and Sofi Paints Her Dreams / Sofi pinta sus sueños (Piñata Books, 2019).

She has worked at The Brooklyn Museum, the Allen Memorial Art Museum and El

Museo del Barrio. Currently, she creates educational material for the Puerto

Rican Heritage Cultural Ambassadors Program at the Center for Puerto Rican

Studies at Hunter College in New York City.

FLOR DE VITA, a native of Veracruz,

Mexico, is the illustrator of Just One Itsy Bitsy Little Bite / Sólo una

mordidita chiquitita (Piñata Books, 2018). A graduate of the Instituto

Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey with a B.A. in Animation and

Digital Art, she currently resides in Jalisco, Mexico.

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

True Blue

truth

/tro͞oTH/noun: the quality or state of being true.

"he had to accept the truth of her accusation"

Similar:

veracity

truthfulness

verity

sincerity

candor

honesty

genuineness

gospel

gospel truth

that which is true or in accordance with fact or reality.

noun: the truth

"tell me the truth"

Similar: the fact of the matter

what actually/really happened

As I've gotten older, I realized that the are things I stopped telling people and explaining. I asked some sister writers Elizabeth Marino and Yolanda Nieves to add their two cents. But before you hear from them, here's mine.

After eight years of living at the poverty level, I've finally decided to write about it. Fair warning to readers: if you are looking for poverty porn, move on. There are enough stories of the desperation, the panic, the self-loathing; as well as the "I found the light inside me after I lost it all." paens.

This won't be about any of that at all. This is about denial and acceptance and what you finally face in yourself.

I am a recovering alcoholic/incest survivor/survivor of domestic violence and death threats. I wrote books, got some of them published, interviewed people like Martin Espada, and read with Juan Felipe Herrera. I went back to school in my late thirties and got a B.A. and an M.F.A. That history, both good and bad, has nothing to do with what I about to say.

I had to face my own powerlessness - over alcohol, over my sexual abuse history, over what I cannot control either within or without me, what casual acquaintances and those I love dearly will do or not no. I have accepted and let go of a million things...

Except for this.

My people are working people, pushing through and working hard always produced some bit of ballast, some piece of rock to stand on, some food on the table.

What I have fought against and am facing is at 63, I might never find another job. Instead of telling myself if I just keep pushing, keep reinventing myself, there will be a place for me right around the corner. I currently have 943 applications on file. I finished a program to be a TEFL instructor, as well as nailing a proofreading certificate.

And yes, I have applied for jobs ranging from hotel front desk clerk, to Walmart greeter, to executive assistant, to Assistant Professor of English....and nada.

The new normal - I live on my social security, about $1000 a month, and whatever else I can hustle. This where the belief that hard work = improving my life passes away.

I stopped thinking about next year, or visiting home, or a more comfortable pair of shoes. I stopped planning for the future, watching a shrinking horizon.

Now l try to eat as well as I can, get enough water, walking and getting some sunshine, and finding one true piece of joy in myself, in my partner, in my day.

At the risk of hyperbole, I fight the wolf, whose teeth are fear, and whose claws can shred your self-respect, if you let down your guard for even a second.

Gente, I'm tired.

I know there are millions out there like me.

I know there is no social contract to take care of each other, to provide a dignified life and death for anyone in this country. Friends have done so much, giving what they can freely, but that is not the safety net I mean.

What I stopped telling people is I'm sure a break is just around the corner.

Elizabeth Marino

As a self-identified socially engaged poet, one’s personal poverty can be flooded by pity, when you hunger for empathy. A sharp, piercing cry of pain is not the full sound of your humanity, and skimps on what you need to say. The literally starving artist, with unstable housing, lack of access to decent health care, and maybe one hot meal a day is as crushed as anyone missing the essentials for material survival. To choose impoverishment in some wrongheaded attempt to identify with some Other or “lift up the voice of the voiceless” ultimately rings false, and an artist must be free to get to one’s own truth of their own conditions. To be of use in the world demands such truthfulness.

I have survived through connection and solitude. One cannot take the hand of opportunity when one’s own hand is trembling and faltering. But one can rest and rise again. Keep holding onto your drive to communicate when much is expressed, as well as to those drafts which help move you along your journey, but do not need to be revealed to others. Delirium might be trippy, but not really nourishing.

One victory for those of us of color is that with the existence of projects like LaBloga, our voices are still here, telling our stories in our own ways. If we truly lack resilience and persistence, why are there volumes of our work, and more in production? If we do not craft our work properly, why are our audiences so moved, and our lines shared among our listeners? Know that there are people who in the name of diversity relish the pornography of our pain more than the tapestry of our living struggle. Keep moving. Keep working.

Yolanda Nieves

I have stopped sharing the story of how I grew up with an alcoholic father and am considered an Adult Child of an Alcoholic (ACOA). I am a survivor of a father who was a benign alcoholic (he’s dead now) and a mother who wrote herself into government history by applying and receiving welfare. I was 9 years old when my father decided he didn’t want to live with us. That began the moment of my greatest shame-paying for grocery with food stamps and realizing my mom, infant sister, and I were going to be immigrants in the land called “abandonment.”

It’s terribly exhausting to keep labeling yourself an ACOA when your father’s been dead over a decade, your mother has found peace with all the decisions she made (like staying married to a damaged human being), and you’ve been through several of years of therapy to figure out you have actually been a decent person all of your life and it was “not your fault.”

I want to address what a “benign” alcoholic means to me. My dad wasn’t interested in anything except drinking. Liquor was the root chakra force that illuminated his world. The bottle was his wife and mistress at the same time. My mom, sister, and I were just the afternoon matinee ticket holders who had to watch a bad movie where the hero is on a one-way trip to hell. He spent all his money on booze, forgetting that he had to pay bills and get groceries for us. Yeah, we were hungry some days. But he gave us provisional alms once in a while.

I suppose he was one of those periodic alcoholics. He would stop drinking occasionally long enough to come up for air and say, “I’m sorry.” My father was not physically or sexually abusive to my mother, me, or my sister. He was, however, an expert in the area of neglect. He loved dogs and devoted a significant amount of love and time to the dogs we somehow adopted when he wasn’t drunk, which is weird because we were the human beings in need desperate need of his time and attention. (My connection with animals comes from the ying yang love/neglect our dogs suffered.)

When he wasn’t drinking, my father would drop everything to help his neighbors. I remember he was attentive to me in this manner: He bought me books. He took me to the zoo, the garden conservatory, amusement parks, and the movies. When I was 8, he bought me a dictionary as a birthday present and gave me direct instructions. “Read it.” And like Malcolm X I started with “aardvark” and ended with “zymurgy”.

So now you understand. It’s complicated, but I have decided to uncomplicate it. As a witness to my dad’s chronic disease, the memories of his ocean-like drinking episodes are still as awful, dark, and traumatizing as the moments they happened. Yet it is possible that I had an idyllic childhood in comparison to other children whose parent(s) have suffered addiction. I still am an ACOA, but it’s not worth mentioning anymore. I had it good. That’s my story. I’m sticking to it

Monday, February 24, 2020

Listen to Me

A short story by Daniel A. Olivas

Listen

to me. I’m not feeling very patient

right now and you seem to be thinking about being somewhere else. But listen to me. Look over there. No, not there. There.

See? See him? Yeah.

His name is Marco. He has a wife,

Octavia, and two sons in this pueblo just outside of Guadalajara. He’s been in San Diego for almost six months

now. How do I know him? Not important. Don’t concern yourself with the little

things. I know his name. Why is he standing there? Simple.

He needs work. For the day. Yeah, it’s hot. Almost ninety I’d say and not even 10:00 yet.

But he needs the money. Look,

look! A truck is slowing down! An old, white Ford with bags of manure with

neat, green layers of turf ready to plant.

Marco’s head just popped up.

Look! And he’s running to the

truck. But two other men get there

first. They get the nod from the

driver. He only wants two. Marco is trying to convince him to take

three. But no. The driver shakes his head. The other two men

are already settled in the truck bed.

And off they go. Marco walks back

to his spot by the lamp post. He would

have been good for that job. He’s young

with a strong back. Planting turf takes

a lot of bending, stooping. Hard work,

especially in this weather. Okay, okay,

I know you need to get to the gym. Why

do I care about Marco? He’s just an

illegal? I hate that word. Illegal.

You spit it out like a tasteless piece of chewed gum. Okay, you want to use that word? Well, let me say what I wanted to say and

then you can go and do your cardio.

What? You don’t want to hear my preaching? I’m not preaching. Just trying to let you know something. About the “illegals” to use your word. What do you mean you don’t have anything to

do with them? Do you eat at

restaurants? Do you stay at hotels? Buy vegetables? Who does your lawn? What?

Hey, you don’t have to use that kind of language. I’m just trying to have a conversation. That’s all.

Come back. Listen to me. Just a minute more. Listen to me.

Please.

Sunday, February 23, 2020

Staten Island Stories: Interview with Claire Jimenez!

In James Baldwin's essay, "Everybody's Protest Novel," he writes: "The failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is read and which cannot be transcended."1 If only Baldwin were alive today to read Staten Island Stories. Claire Jimenez's well-crafted stories affirm life by fearlessly baring all: the beauty, the dread, the power and failure of the human condition while also offering the reader every intersectional aspect of the characters that readers meet on this journey. Jimenez has mentioned that Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales was an inspiration for this collection. In The Canterbury Tales, the characters unite for their yearly pilgrimage to the shrine of St. James, better known as Santiago de Compostela (in Spain). The reader becomes familiar with each character while they tell their stories as they journey to the holy shrine. Here in Staten Island, there is no holy shrine. These characters are simply on a daily road to survive on an island where they are faceless, invisible. New York itself is very diverse. But Staten Island's demographics are predominantly white, 75.7% white to be exact while 10.6% are Black or African American, 7.5% are Asian, and the Latinx population stands at 17.3%.2

Jimenez is giving voice and a presence to these individuals. As we begin the collection, she places us on a journey above ground, on the ferry, with a struggling adjunct professor : "Today on the way back home from teaching . . . "(1). She ends the collection underground, interweaving all five boroughs of New York: "The hot trains stuck underneath the city, and all of the people crawling out of their doors, then along the wet, dark tunnels, unable to see. Arms extended in front of them like antennae as the roaches scurry away from their fingers" (157). In between, we are treated to colorful descriptions, elegant prose and dialogue depicting the beauty and heartbreaking pain these individuals carry with them.

We are lucky to have Claire Jimenez on La Bloga, to talk with us about her own journey in the writing of Staten Island Stories.

Montes: Thank you, Claire, for joining La Bloga today! Tell us about yourself.

Jimenez: I'm a Puerto Rican writer who was born and grew up in Brooklyn and Staten Island. Currently, I'm a PhD student in English at The University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I received my MFA from Vanderbilt University, but spent a large part of my career working in youth development. Specifically, I spent years working at a community center in Stapleton. But I also taught for many years all around New York City as an adjunct college instructor and a teaching artist.

Montes: The community center and teaching all around New York City, I'm sure, were important for the making of your collection. You mention that The Canterbury Tales was an inspiration. And Actually, some of Chaucer's stories like "The Knight's Tale" and "The Grant Writer's Tale" certainly bring his work to mind. How are the journeys different here?

Jimenez: Like Chaucer's characters, mine are constantly in motion. I think that's true for many people living in New York City. But for Staten Islanders working in other boroughs, this is especially important. Often our commutes require the boat, the bus, and the train. I spent most of my life living and working in New York, and so much of my experiences have been shaped by that movement. It seemed that any collection exploring Staten Island would have to take account of our connection to the water and the ferry and how that shapes life inside the Island. Chaucer's characters are traveling towards a holy shrine, while mine are just trying to get to work on time. But in this collection, I try to show how the stakes are just as high.

Montes: In "The Tale of the Angry Adjunct," we see the struggles, the painful struggles of an adjunct professor seeking a better life. Throughout the U.S., such a story is not unusual. In Los Angeles, for instance, a large percentage of adjuncts are enrolled in various public assistance programs or many are sleeping in their cars.3

Jimenez: I taught as an adjunct for many years on top of working at a community center and an arts council. It's grueling, underpaid work. There's also an instability about it because you never know if you will be assigned classes the next semester. As a result, you always accept courses when they're offered to you so that you can save money in advance. It's such a different reality than the characters of professors we often see depicted in movies or pop culture. Adjuncts are working class and sometimes living at or below the poverty line. At the same time, many adjuncts have the privilege of extensive higher education. It's a weird tension. In many ways, they represent the brokenness of a system that promises if you work hard, if you go to school and do well, you'll turn out all right. So, I knew when I wrote this collection, I wanted to include that story.

As I wrote the story and learned more about my main character, I realized that Lauren O'Hare was a white woman who was also dealing with her conflicted feelings of her parents voting for Trump. I thought her own disappointment and disillusionment with academia thematically fit in well with the conflict she experiences with her parents. In many ways, this is a story about class consciousness.

Structurally, I began with the adjunct story because when I was adjuncting at CSI [College of Staten Island CUNY] and Wagner College, I often assigned personal narratives in my freshman composition classes. Chaucer starts The Canterbury Tales with a prologue that introduces the different characters. I decided that my collection would start with a teacher who in the ending scene loses all of her students' essays. I wanted her story to introduce us to the voices of those different characters in the same way that Chaucer's prologue does.

Montes: And these interactions with all your characters: the families, mothers, daughters, brothers are visceral and so real. I'm thinking here of "You are a Strange Imitation of a Woman," where Carlos and Frances have it out. Their profound pain reveals itself in such a riveting way.

|

| Claire Jimenez |

Jimenez: That story is the oldest in the collection. I wrote it my first year at my MFA program in Vanderbilt in a workshop with Lorraine Lopez. And it's my favorite story, because I think it was one in which the action rises most organically. I'm interested in mental illness and power and how violence manifests itself in the home between people who love each other. I'm also interested in intergenerational violence and how that gets reproduced. How are these things linked to colonialism, class and race? Those are all big themes, but I feel like with that story, I was able to begin with the particular to get to those larger questions.

Montes: You also play with point of view, offering the reader interesting perspectives as in "Do Now" which is in second person. How did you decide on the POV (point of view) for which stories?

Jimenez: I knew I wanted most of the stories to be first person narratives, because I was thinking of them as those personal narrative assignments I used to assign to my students. "Do Now" stands out because it is an older story. But I thought it would fit in with the collection, because even though it's a second person point of view, it's one that's exploring how Miranda has internalized the voices and criticism around her. In this way, it is a portrait of her own psyche, one that has been so compromised by violence and racism that it is difficult for her to say, "I." In this way for me, "Do Now" is still a a personal narrative.

Montes: In "Underneath the Water You Could Actually Hear Bells," the buoyancy (pun intended) of these characters' interactions, their expectations and disappointments echo powerfully on this "journey" due to the elegance of the dialogue. What do you think makes for good dialogue?

Jimenez: Thank you, Dr. Montes. That is very kind. I love dialogue and scene. I think that's my favorite part of writing, hearing my characters talk to each other. I think dialogue is made of several components. When I am creating my characters, I have to figure out how they would speak. What's their voice? What are things they are always saying? I also ask myself what would this character never say? Why would they never say this thing? What do they say instead? That's how you arrive at subtext.

Montes: Thank you so much, Claire, for agreeing to interview with La Bloga. We are wishing you much success and I encourage everyone to read Staten Island Stories!

_______________

1 You can read James Baldwin's entire essay at: https//africanamericanrhet.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/jamesbaldwinprotestnovel.pdf

2 http://worldpopulationreview.com/boroughs/staten-island-population/

3 Click HERE for further reading on the difficulties many adjunct professors experience.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)