When I was a kid, if I had told my dad

I wanted to go on a “play date,” he’d probably have answered, “Why

don’t you go on a real date?” The problem was that in the 1950s-70s, the term

hadn’t been invented. We had no conception of a “play date,” a term that might even give deconstructionists a run for their money.

Each summer, in

the westside suburbs of Los Angeles, as kids and into our adolescent years, my

friends and I would just meet in front of George’s house on our bikes (after finishing

our chores), decide what to do, and take off, sometimes dumpster diving,

looking for model airplane parts behind the Wen-Mac Corp building, discarded pieces

of pottery and china from Sasha Brastoff, or electronic gadgets from electronic

firms like Gilfillan and Magnavox.

The closest thing

to a “play date” was meeting early, packing a bag lunch, and riding our bikes up Bundy Drive towards the Santa Monica Mountains, find a place to

climb the hills, and just hang out for the day, or maybe jump on the bus to

Sorrento Beach, next to the Santa Monica Pier, and ride the waves all afternoon.

When our imaginations faltered, we’d default to the neighborhood park, play whatever

sport was in season, and end up in the “pool,” (what my parents called the “plunge”),

playing tag, tucking our bodies into cannonballs and jumping from the tower, dunking each other, or playing Marco Polo until we dropped from exhaustion and lay out under the sun.

During school, it

was trickier, no “play date,” but a little scheduling, like reporting home to

let Mom know I hadn’t been kidnapped, do my homework (if I couldn’t talk her

out of letting me wait until later), be ready at the dinner table, so when Dad came

home we could eat; then, if there was still light, I’d hit the streets, where

there’d be a at least ten other kids waiting to play, “Red-light, Green-light,”

Hide ‘n Seek, Simon Says, or football in the street, ‘til dark. In our teen

years, we’d meet-up, guys and girls, at the neighborhood park, which was our

Vegas, you know, “What happens in the Park, stays in the Park.”

It was the same

with my own kids, the two oldest, born in ’70 and ’72, when they reached the

age of mobility, they’d be outside playing with the other kids, a mixture of

Chicanitos and Chicanitas, maybe a Japanese and an Anglo kid. Even my youngest

daughter, who came along in 1980, had a lot of liberty to run around and play

outside without having to schedule it onto a calendar, but, by then, I began to

see the change, fewer kids, the parks near-empty, schools closing for lack of

enrollment, and not even enough kids to form sports teams.

I still didn’t

hear about the “play date” concept of youth entertainment, not until my

grandkids came along, and I thought it strange the idea of scheduling kids’ play

time. Standing outside the school, Mrs. Brady would ask Mrs. Reyna and Mrs.

Chen if Chato and Wei could come to the Brady house for a “play date” with

Skylar on Saturday? Once it was set, they put it on the calendar

and wait until Saturday, but until then, the kids, apparently, just stayed

home.

That’s when I

noticed fewer kids riding bikes or skateboards on the sidewalks or streets. At

the neighborhood parks, everything was systematized, parents, or nannies, watching

kids on the swings and slides, the courts and fields reserved for organized sports,

inside a building a dance class, or a child-care class, no kids in cut-off

jeans or, heaven forbid, barefoot, but everybody in the newest, most popular

sneakers and Oshkosh shirts, careful not to get dirty.

Gone were the

bikes and the kids climbing trees or playing a pickup game of basketball,

baseball, or football, not even soccer. In the 2000s, the “gaming” craze hit,

kids stuck to computers and phones, and as for free, outdoor play--forget about

it.

Even today, as I

visit various parks throughout L.A.’s westside to walk my dogs, twice a day, it’s

rare to see kids running around without adult supervision. Mostly, adults,

doctors, lawyers, and real estate agents have monopolized the courts and fields,

Saturday, scheduled for kid sports teams.

I live in a two-bedroom,

one-bath, suburban home in an area where, in the 1950s and ‘60s, kids filled

the streets. Today, it’s adults jogging or walking their dogs. Occasionally, a

young couple will come by holding on to a toddler. No go-carts, homemade scooters,

not even a skateboard in sight, except at the skateboard park, but only during

specific hours.

In

Bless Mi, Ultima, Rudy Anaya’s

Chicano classic, rural, New Mexico post-1940s’ kids meet up near the stream and

ponds hoping to see the golden carp, the largest, most majestic fish in the

water. I’ve read the book a number of times, and I have to confess, I had a

hard time believing such a fish existed, even in fiction. Still, to the kids,

the main characters in the novel, the golden carp was real, a god among all the

other fish, if they were among the lucky ones to see it.

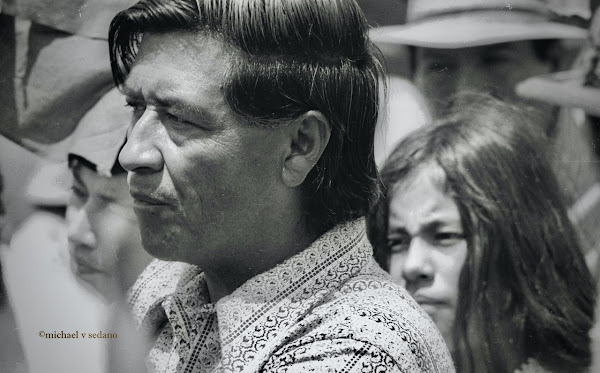

I met Rudy one

day when a friend invited me to hear him lecture at Cal Lutheran University,

out in Simi Valley, back in the 90s. I just happened to see Rudy getting down

from his car. I approached and introduced myself and said that I was there to

hear his talk. He recognized my name and told me how much he enjoyed first book,

Pepe Rios.

He was due to

talk twice, once in the morning and again at night. I had only planned on

staying for the early talk, but when he asked if I’d be hanging out for dinner and the

evening lecture, how could I say no. I stayed and was so glad I did. Well over

200, mostly white, students, faculty, and staff showed up, mesmerized by his

stories of curanderismo, a beautiful sight I still recall fondly.

Years later, as I

thought about childhood and “play dates,” I thought about Rudy’s golden carp, as I stated earlier, a challenge to what Coleridge called “the willing suspension of disbelief.”

But what always

affected me was Rudy’s writing, the beautiful language, and the emotions surrounding

the golden carp, a sense of magic and wonder, an epiphany, I guess, and the magic

wasn’t in the golden carp at all. It was in the mystical nature of childhood, a time of exploration, adventure, innocence, and ultimately, loss, for many, as violent and life-changing as a tumble into Dante's Paradise Lost.

In those immediate,

post-Depression and post-WWII years, whether living in a rural, suburban, or

urban area, we, children, often encumbered by our parents’ problems and emotional

injuries, could wander freely, play in the street, ride bicycles, fill the

athletic fields without an adult in sight, frolic at the parks, take buses

around town, or just lie about under the sun and daydream. Rudy’s

golden carp captured the marvels of childhood.

Oh, sure, I understand

all the reasons for change, for progress, for "play dates," and as surely as lighting strikes, so does reality: rampant materialism, the “pill”, gentrification,

the proliferation of private and magnet schools, busing, the expenses of child-rearing,

technology, and the fear (real or imagined) of letting kids roan about freely, yet,

by scheduling every hour of a child’s day are we limiting children’s need to imagine, explore and discover the golden carps outside their doors, or as my father might say, to have real dates instead of play ones.