Thomas & Mercer

From award-winning author Deborah J Ledford comes a thrilling new series featuring a Native American sheriff’s deputy who risks it all to find a friend who’s gone missing.

After four women disappear from the Taos Pueblo reservation, Deputy Eva “Lightning Dance” Duran dives into the case. For her, it’s personal. Among the missing is her best friend, Paloma, a heroin addict who left behind an eighteen-year-old son.

Eva senses a lack of interest from the department as she embarks on the investigation. But their reluctance only fuels her fire. Eva teams up with tribal police officer and longtime friend Cruz “Wolf Song” Romero to tackle a mystery that could both ruin her reputation and threaten her standing in the tribe.

And when the missing women start turning up dead, Eva uncovers clues that take her deeper into the reservation’s protected secrets. As Eva races to find Paloma before it’s too late, she will face several tests of loyalty―to her friend, her culture, and her tribe.

Deborah J. Ledford is the award-winning author of the Eva "Lightning Dance" Duran suspense thrillers. These Native American novels of suspense are set in Northern New Mexico and on the Taos Pueblo Reservation.

Part Eastern Band Cherokee, Deborah spent her summers growing up in the Great Smoky Mountains region of North Carolina, where her Smoky Mountain Inquest novels are set.

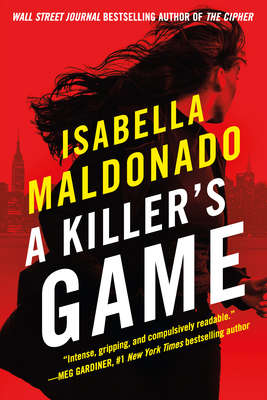

FBI agent and former military codebreaker Daniela “Dani” Vega witnesses a murder on a Manhattan sidewalk. The victim is chief of staff for a powerful New York senator. The assassin turned informant is Gustavo Toro. His code: hit the target and don’t ask questions. When Dani suspects a complex conspiracy, the only way to take down the mastermind is from the inside, forcing her to partner with Toro. Together they must infiltrate the inner circle at a remote facility.

Except it’s a trap. For all of them.

Locked in a subterranean labyrinth and held captive by an unseen host, Dani, Toro, and others must fight for their lives. Now Dani must stay undercover, unravel a bizarre conspiracy, and survive lethal puzzles. But will Toro be friend or foe? Because in this killer’s game, everything is real: the paranoia, the desperation, and the body count. And only one person can make it out alive.

The murder of jazz musician and social activist Markus Peña doesn’t come as a surprise to his estranged sisters. Melinda and Emily Peña know their controversial brother had enemies. After all, even they hadn’t spoken to Markus since their mother’s funeral two years ago.

Who killed Markus? Was it someone trying to keep his latest protest song from publication? Was it the powerful and secretive uncle of his ex-girlfriend Rebecca? Or was it one of the other women Markus had callously abandoned?

To unravel the truth, Melinda and Emily must first face their own demons. Melinda, a former social worker, suffers from PTSD ― haunted by the people she failed to help and unable to maintain meaningful relationships. Emily also pushes people away ― afraid she’ll get hurt and afraid they’ll find out she’s Three Strikes: a masked vigilante who violently punishes abusive men.

Markus wasn’t a good man, but he was family. And it’s up to his sisters to uncover his lifetime of lies and the truth of his death.

Haunting, gripping, and relevant, No Home for Killers explores the conflicts that tear families apart―and the tragedies that force them back together.

Vera Wong's Unsolicited Advice for Murderers

Jesse Q. Sutanto

Berkley

Vera Wong is a lonely little old lady—ah, lady of a certain age—who lives above her forgotten tea shop in the middle of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Despite living alone, Vera is not needy, oh no. She likes nothing more than sipping on a good cup of Wulong and doing some healthy detective work on the Internet about what her Gen-Z son is up to.

Then one morning, Vera trudges downstairs to find a curious thing—a dead man in the middle of her tea shop. In his outstretched hand, a flash drive. Vera doesn’t know what comes over her, but after calling the cops like any good citizen would, she sort of . . . swipes the flash drive from the body and tucks it safely into the pocket of her apron. Why? Because Vera is sure she would do a better job than the police possibly could, because nobody sniffs out a wrongdoing quite like a suspicious Chinese mother with time on her hands. Vera knows the killer will be back for the flash drive; all she has to do is watch the increasing number of customers at her shop and figure out which one among them is the killer.

What Vera does not expect is to form friendships with her customers and start to care for each and every one of them. As a protective mother hen, will she end up having to give one of her newfound chicks to the police?

Lila Macapagal’s godmothers April, Mae, and June—AKA the Calendar Crew—are celebrating the opening of their latest joint business venture, a new laundromat, to much fanfare (and controversy). However, what should’ve been a joyous occasion quickly turns into a tragedy when they discover the building has been vandalized—and the body of Ninang April’s niece, recently arrived from the Philippines, next to a chilling message painted on the floor. The question is, was the message aimed at the victim or Lila’s gossipy godmothers, who have not-so-squeaky-clean reputations?

With Ninang April falling apart from grief and little progress from the Shady Palms Police Department in this slippery case, it’s up to Lila and her network to find justice for the young woman.

The Calendar Crew have stuck their noses into everybody’s business for years, but now the tables are turned as Lila must pry into the Calendar Crew’s lives to figure out who has a vendetta against the (extremely opinionated yet loving) aunties and stop them before they strike again.

Nikki Finch is a successful transgender woman with a thriving Beatnik cafe and a comfortable life until the first summer of the Trump presidency sets off a wave of violence against minorities. Nikki’s carefully curated world is shattered when a neo-Nazi thug attacks her business partner. She comes to his rescue, but her efforts launch a chain of events that imperil her and everyone she loves, especially her angst-ridden daughter, Morgan. Nikki will do everything she can to keep her loved ones safe, but as her civilized options begin to evaporate, she is left with no choice but to go places she’s never gone before.

Kill or be killed. It should be a simple choice. But it’s not that simple for Nikki Finch—it would have to be a cold-blooded murder and she’d have to get away with it. It could work, but what kind of example would she set for her daughter?

Manuel Ramos writes crime fiction. Read his latest story, Northside Nocturne, in the award-winning anthology Denver Noir, edited by Cynthia Swanson, published by Akashic Books.