Note: March roars in like a mouse that roars and catches La Bloga-Tuesday's Michael Sedano in the midst of major transitions. Let change arrive on its own time. In the meanwhile, we gotta read, and we gotta eat gluten-free comida.

Expanding Limits, Making New Rules, Setting History Straight

Review: Rudolfo Anaya. Chupacabra Meets Billy The Kid. Norman:UOklahoma Press, 2018.

ISBN 9780806160726

Michael Sedano

Rudolfo Anaya continues expanding the horizons of Chicano Literature in his newest work, Chupacabra Meets Billy The Kid in so many ways. First off, the title is sleight-of-hand. While folklorists might come looking for some Chupacabra, a sci-fi platonic romance breaks out. Beyond that, let me count the ways Anaya is busting Chicano Literature loose from conventionality and celebrating himself. And if I’m wrong, I trust I’m not alone in celebrating Rudolfo Anaya’s ongoing enrichment of literatura Chicana with this exploration of the speculative muse.

For one, Chupacabra Meets Billy the Kid is a valedictory-in-progress for Anaya’s oeuvre by the author himself. For another, the author, a descendant of the New Mexico legend, sets the record straight about his forebearer. Then there’s the novel of the title, a science fiction plot knitting together the goat-sucker with la llorona, Big Foot, space aliens, an infested office of the U.S. president. There’s a meta-novel unraveling in the process. From University of Oklahoma Press, Chupacabra Meets Billy the Kid arrives as the year’s most entertaining title. Anaya sets the bar for 2019 U.S. Spec-Fic.

For one, Chupacabra Meets Billy the Kid is a valedictory-in-progress for Anaya’s oeuvre by the author himself. For another, the author, a descendant of the New Mexico legend, sets the record straight about his forebearer. Then there’s the novel of the title, a science fiction plot knitting together the goat-sucker with la llorona, Big Foot, space aliens, an infested office of the U.S. president. There’s a meta-novel unraveling in the process. From University of Oklahoma Press, Chupacabra Meets Billy the Kid arrives as the year’s most entertaining title. Anaya sets the bar for 2019 U.S. Spec-Fic.In one hundred seventy-two pages, the author weaves threads drawn from the fabric of his literary output. Curandera and mystic Ultima hovers on the outskirts of the action, these settlements are her haunts, the whole llano, is her tierra. As the story draws the character Rosa home, the author reminds readers of her origins, it carries her home:

The golden carp from a story told by the man who had told Ultima’s story. She had seen the boys fishing at the river when they left Puerto de Luna. Now the carp had appeared, a miracle.

Other tokens of the Author’s career step forth aside from that magical carp; those muchachos from young Mares’ boyhood; place names; Anaya’s familia, even Roberto Cantu makes an appearance. These allusions offer metynomic cameos concatenating all the words and characters who’ve come before in Anaya’s life, culminating for the moment, here. It's not that this title stands alone, it belongs to this long-lived familia of created truths.

Chupacabra’s science fiction angle has its origins in Anaya’s Sonny Baca series that begins with Alburquerque and follows the seasons, Zia Summer, Rio Grande Fall, Shaman Winter. The detective’s nemesis, Raven, brings mysticism and time travel to Sonny’s world in that final title, in a bit of a fictive stretch then. Time travel is the central motive of today’s plot, and it works.

Unchanging and unchangeable, time travel makes for one long bitter irony for Rosa. She knows how the stories end. The girls she hugs farewell, they’ll be dead from disease a few years after Rosa’s hugged them and wished them long lives. Billy, too, is headed for his death.

People who read history get it. Pat Garrett was a hero. People who read more history, and fiction, get it, too. People related to Billy, like Rudolfo Anaya, and country gente, think of a cowardly blast, a kid singled out by double-crossing land barons, not the only killer in town. That's the story Rosa tells here.

Don Rudy adopts a female persona for Chupacabra’s lead character. She’s a novelist frustrated because, writing yet another Billy the Kid story, she feels its absence of authentic, of things and people not known anymore. All those women of the llano, the ones Bilito romanced, the ones who endured and gave succor after drunken gunfights to men with names. Research carries one only so far. Seeing is believing and the ultimate research. It's like Rosa makes a deal with the forces of nature.

The novel itself contains no surprises. The kid lives a short, violent life and gets gunned down and buried. End of story. What was his name, this Billy the Kid? Anglin? Bonney? Henry McCarty? The characters are what give the novel its fresh life. Rosa the researcher keeps novelist’s notes that leap from date to event to person. Rosa the storyteller seeks out the women whose stories didn’t get told, who lived in between those facts.

Rosa recorded the names of the families she met in the Pecos River villages. They always welcomed her into their homes, gave her a place to sleep, shared their meals. The women were the strength of the family and community. Work was strenuous and difficult for the men outdoors, and just as hard for the women. Raising families, preparing meals, canning for winter, making soap from lard and lye, washing, sewing, gardening, sometimes riding to the range to help with shearing sheep or branding cattle, bringing in water from cisterns or the river, chopping wood, cooking three meals on a wood-burning stove, attending church, raising chickens, having babies, curing every conceivable illness that struck family or neighbors, helping their comadres: the list was endless and exhausting.

For me, what I call the meta-novel offers the best moments of Chupacabra Meets Billy The Kid. Like a Shakespearean dramatic monologue, the author steps outside the narrative to offer writerly consejos about the creative process, an historian’s gloss on a particular detail, something the author needs to tell his readers at this juncture. For example, expounding on evil, Anaya has Rosa ask “What does this have to do with me?” and the reader should take that “me” as themselves.

“For starters, we know that most Advanced technological civilizations destroy themselves in their infancy. Nations create weapons, and once each country has its nuclear arsenal, political forces keep adding to the stockpile. No one wants to disarm. When we acquired nuclear weapons, we fit the rule. You only have to look at the proliferation that’s taking place, loose nukes being sold to terrorists. A crazy president with his finger on the nuclear button.”

The voice is Marcy, a disembodied character from an earlier novel, a voice in the machine who guides Rosa’s travels through space and time. Marcy is also Anaya’s voice, the omniscient metaphysical narrator hanging--perhaps impaled-- on the point of the Arrow Of Time.

Time, travel, space, the critters, these elements make up the whole cloth of the meta-novel. Anaya devotes some explanation to how Rosa gets to nineteenth century New Mexico. It’s not clear why Billy isn’t freaked out that he understands Rosa’s presence, but he’s of his time and of the future, multidimensional, as in this scene:

Billy forced a nervous laugh. “Maybe that’s why I don’t trust the written word. Most written about me is lies. You tell ‘em the truth, Rosa.”

Billy could not look into the future. Many books had already been written about him. lies and truths. Each reader had to come to his or her own conclusion about where the truth lay.

Rosa nodded. “I’ll try, Billy.”

After two years in Billy’s time, Rosa rides a horse upriver and into her own time. Do the people in Billy’s time think Rosa stole Mancita, the horse she rode into the sunset on? Why doesn’t Rosa’s laptop run out of juice? Is it because in her own time, she's been gone just a few hours?

Readers need to sit back and enjoy the ride. Sci-fi is supposed to make sense, but only up to a willing suspension of the rules. After all, the imagination’s the limit, and Anaya’s muse lets loose a todo dar page after page. For example, a classic scene borrowed from the stopped clock showdown scene in a movie.

Rosa’s helplessly worked up seeing a jailer bully pounding Billy’s face with the butt of a rifle. Rosa gets kicked out of the jailhouse and comes face to face with the devil, a creature named “Saytir.” This is a formidable enemy, only a hidden derringer saved Rosa the last time she was alone with the alien spawn from her own time.

Saytir wore purple bell-bottom pants with silver rosettes sewed down the sides of the legs, a bright red shirt, and a dazzling blue satin vest. His neckerchief was pink, his hat a poor excuse for a large mariachi sombrero. His boots were obviously from a Juárez Mercado. On his gun belt he sported two silver pistols, one on each hip.

“Rosa,” he whispered in his best imitation of Gary Cooper in the movie High Noon. “We meet again.”

The ridicule is Anaya's most trenchant indictment of daily events. Much as the evil is a clownish buffoon, Saytir's power can destroy the world and only Rosa has the answer, it's tied up in the inevitability of Billy's legend, in the writer's power to suspend time and write events to fit their outcome.

Filling in Billy’s story demands mas o menos straight history, or in this narrative, fashioning creative non-fiction heavy on the fiction element, as Anaya develops the facts of the Lincoln County war. For readers with an historical bent, there’s a set of research notes at the end that links plot events to history. In other words, this stuff really happened, the names have been supplied to tell the fuller story.

Ultimately, Billy’s story is satisfying because of its fantasy—the time trip, the monsters, are supposed to be fun. And they magnify the horror of the truth. Big Foot and cyborgs aren’t real but that evil is. Marcy and Rosa step away from Billy’s narrative to address, engage, a writer’s ethical responsibility to record, document, reveal, explain. Marcy talks:

Write Billy’s history. Let people know we have this self-destructive instinct in us. It’s what led to the violent times in Lincoln. But there was some good in Billy. If you can find some goodness in Billy’s life, that’s the lesson to be learned and taught to the young. Otherwise, we’re lost. Your story can save the world.”

“ I didn’t set out to save the world!”

“Few writers do, and yet that’s your mission.”

At this juncture the transmission fades and Rosa and the reader are on their own. Billy gets buried. Rosa rides home with Josefa’s blue taffeta dress. Time returns to normal. None of this happened. Evil abounds. The

Order Chupacabra Meets Billy The Kid publisher-direct at this link. Independent booksellers can order it for you.

The Gluten-free Chicano Cooks

Kathy and Jim Build a Boat. Boatyard chile verde.

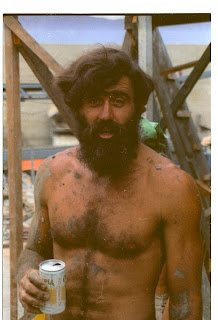

Durf marveled at his teammate, a javelin thrower who lived in the Goleta monte. A born storyteller, my roommate spun a fanciful tale of a man I knew only by sight from track meets. I sought what germ of truth must lie at the heart of Durfee’s account.

|

| Jim Clark back to camers |

Jim Clark’s girlfriend, Kathy, loved him with immense dissonance. Jim’s life was impossible to share with a woman studying to make a career teaching high school English. It was during one of their off-again separations that Kathy and I were hanging around together.

Kathy filled whatever space she occupied. Not many people chose to occupy space with her, however, because Kathy spoke her mind. A woman of wit and brains, Kathy was a formidable personality who fit perfectly into my world, especially as we both were single and not looking. An ideal end-of-college-summer partnership.

Four years have ways of changing a person’s life and attitudes. I was back from overseas and learned from the locals that Kathy and Jim lived in the boatyard along the railroad tracks. They were building a boat and needed help. I called the boatyard. I hadn’t heard Kathy’s voice in four years but I recognized her “hello?” instantly and she mine. Old friends are good friends, separations are meaningless.

I asked him about the javelin story. “I tried it one time,” Jim Clark laughed. That was the day we laid the keel for the cement boat.

|

| Kathy looks out while Jim and friend cement the deck. |

I drove the car into the weeds where Jim directed me to stop with the rail underneath. Jim and another fellow lifted the front end and I lashed it to the front bumper. We did the same on the other end.

The nose of the rail extended a few feet from both ends of the Buick Skylark. Slowly and not spotted by cruising cops or railroad dicks, we drove the back streets to the boatyard and dropped the keel in place. In the boatyard shack’s two-burner propane stove, Kathy made her famous dumpster soup and we feasted friendship, old times, the cement boat to be.

A few months after, the boatyard shack has gained a dining table, an outdoor couch and several makeshift seats. Where we’d dropped the keel now stood a rebar and steel wire superstructure of a 40-foot boat. Jim worked on that boat with the intensity that led him to think he could chase down a deer and kill it with his javelin. The deer was certainly out of reach but Jim had built a boat. All it needed now was a skin of cement.

Months passed as Jim constructed the hull, deck, interior spaces and hidden recesses. The work took the time required. Ugency arrived with cementing. The work must be completed in one weekend so the boat dries and cures as a single mass of cement and steel that floats on the open sea. Friday after work, Barbara and I drove up from Temple City. The work was well underway by our arrival late afternoon. Jim and Kathy had lots of friends.

|

| Jim Clark. qepd. |

The third day the hull looked like a boat. Only a few people fit inside so workers took shifts pounding cement into the interior walls. Others touched up the exterior. By noon Sunday, the cement boat was done. Most of the crew had left, exulting in knowing they’d joined the culmination of an incredible feat. Jim had read books and talked to old salts, he and Kathy moved into the boatyard, and they built that boat by hand.

I volunteered to make the celebratory feast, a one-dish meal I call Boatyard Chile Verde. After Jim and the cement boat were taken by pirates in southeast Asia, Kathy sailed those waters in hopes of word. She cooked Boatyard Chile Verde for merchant mariners the world over, it was the crew’s favorite dish.

You can make this on a one-burner propane stove, or in a sartén over an open fire. Ingredients, improvisation, and preparation are the keys to making Boatyard Chile Verde.

INGREDIENTS

Pork. Sub beef or chicken.

Gf flour.

Tomatillos.

Green chile – hatch, California, mild new mexico, canned whole are fine.

El pato hot sauce.

comino

Onions

Garlic.

Cilantro

Cast iron frying pan and lid.

Paper or plastic bag.

Sharp knife.

Salt

Pepper

Chile powder

Olive oil

Into the bag, put a ¼ cup of gluten-free flour, a pinch of salt, pepper, and chile powder.

Wash and dry the (pork) meat.

Cut the meat into ½” cubes.

Dust the meat with seasoned flour in the bag.

Dice a large onion and six or eight garlic segments.

Chop cilantro to make 1/8 cup.

Chop 6-8 large tomatillos

Get 1/8” of olive oil hot in the pan. High flame.

Wilt the onion and garlic, stir don’t burn.

Toss the meat cubes with the wilted onions and garlic.

Season with salt, pepper, ground comino or a pinch of seed.

Brown.

Add the chopped tomatillos and chopped fresh/canned chiles, and the can or two of el pato.

Stir and cover.

Lower heat to medium and bring to a boil.

Lower heat to lowest simmer setting and cook for an hour, stirring now and again.

This is ready to serve right away. The objective to fork-tender bits of meat that look like meat, not a paste. Cook vegetable longer before adding chicken, then simmer raw chicken fifteen or twenty minutes until firm. Chicken is fast. Cook beef an hour and a quarter, maybe longer.

No comments:

Post a Comment