Review: Désirée Zamorano. The Amado Women. El Paso TX: Cinco Puntos Press, 2014.

1-935955-73-X

Michael Sedano

Love is complicated, not the many-splendored thing of songs of yore. Take the four Amado women, for instance. In their own way, each is loved, or finds love, or thinks she does, in Désirée Zamorano’s first novel for Cinco Puntos Press, The Amado Women. But there’s a wide gap between perceived love, and happiness. Zamorano is not kind to her characters in ways that will unnerve some readers, but at the end of the book, the reader is going to want more.

There’s Nataly, a soltera artist who doesn’t finish her projects and finds lubricious sex with another woman’s man. There’s Sylvia Levine, wife and mother of two little girls, in a brutal loveless marriage. There’s Celeste, a damaged divorcée who has buried her only child and alienated herself from the familia. There’s Mercy, the sixty-year old mother who finally dumped her old man and started making her own life. Women’s lives are complicated.

Men are less so. Men are shits. There’s a medical doctor who won’t listen to a child’s complaints yet ignoring them could be lethal. There’s Amado père, a philandering jerk who turns mawkish when Mercy dumps him. There’s Nataly’s married lover who wants sex, not love nor companionship. She doesn’t see that. There’s one decent guy, Celeste’s friend, whose passion she refuses to allow. Then there’s Jack Levine. All you need to know about this brutal asshole is in the novel’s opening pages. There’s a lot more to Jack and his own love life, but to share details would be a spoiler.

There are two more Amado women, the Levine girls. Is their future to replicate the other Amado women’s? And like mom, the children are in danger. Daddy doesn’t like Becky, the youngest. Becky’s body hurts but her bruises don’t show, either. Like mother, like daughter? The first-born, Miriam, perhaps is daddy’s girl and doesn’t get beaten. When Sylvia does something “wrong”, the first words out of Miriam’s mouth when daddy walks in the door are to snitch on mom and Becky. Of all these people, Miriam may be in the greatest danger, danger of growing up to be a survivor through connivance. Again, to reveal details will ruin the twists that Zamorano skillfully crafts for her readers.

As one reads the stories of these four women and two girls, a reader begins to question if Désirée Zamorano is being ironic with that surname. Are these women loved? Do they know love, or is their experience the detritus of love? Might the only genuine, lasting love be that between mother and child?

As Zamorano’s novel unfolds, the latter seems the most accurate assessment of these women’s lives. Sisterly love is just as complicated as women with men. Nataly and Celeste are at each other’s throats. Nataly, the youngest and her mother’s favorite, resents Celeste’s decision to leave their home town of Orange for school in Arcata. Celeste went off to Humboldt State and never came back. For her part, Celeste sneers at her sister’s art career and privately gloats that Nataly works as a waitress while her art career goes nowhere. Sylvia keeps secrets from her family, instead shares the private details of her hellish life with a confidante.

Désirée Zamorano’s focus is these women’s experience, electing to zoom in on the drama and skimming over what the women look like. Are they brown? Except for a smattering of Spanish phrases and a child who chokes to death on a tortilla de harina, we don’t really see them as ethnic, nor as others see them.

Women aren’t their looks so Zamorano gives little attention to superficial matters, describing women in general terms and tokens like purses. Nataly is beautiful. Celeste has short spiky hair. Mercy touches up her canas. Sylvia has bruises that don’t show, and money that does.

Zamorano has chosen to downplay physical appearance, so vital to a woman’s place in contemporary culture. Not until the action is spinning down does the author let the reader “see” what some of the characters look like, the New York artist, the confidante. These moments of recognition at the end of the book enhance the story, adding dimension to minor, but key, players, and a measure of ineluctable satisfaction, even if looks don’t matter.

With her characters reeling through yearning, loneliness, illness, discord, tragedy, unfolding crisis that brings them together, Zamorano allows the superficial issues of appearance to provide momentary respite from some really terrible events happening to people whom we care about, even if they don’t care as much as the reader.

With so much in this novel that a reviewer cannot talk about, what, then are we to make of the Amado women? When the reader steps back from the page inductively and looks for connections between these particular women and women generally, the fog begins clearing. The Amado Women is a novel about consequences and accountability.

Bad decisions lead to messy outcomes. Indecision leads to a damaged spirit and worse—Sylvia. But so does hasty decision--Nataly. Doing the right thing for oneself is something that requires risk—Celeste and Mercy. Then outside forces beyond one’s influence or control happen, and knock one for a loop. The woman who is reluctant to take a reasoned risk is unprepared for life’s vagaries and will live one of those lives of quiet desperation that demand a second novel to resolve all that unfinished business.

I hope that’s Désirée Zamorano’s plan because I want to know what happened after the final page.

Visit Cinco Puntos Press to order a copy, or ask your local indie bookseller to get your copies through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution.

Altadena Event Brings Delightful Surprise

It was a difficult weekend in that far too many wonderful events were scheduled for the same time across the Los Angeles basin. In my neck of the woods, Luis J. Rodriguez was reading at the Pasadena main library and later that day part of a Poet Laureate Address to the Nation.

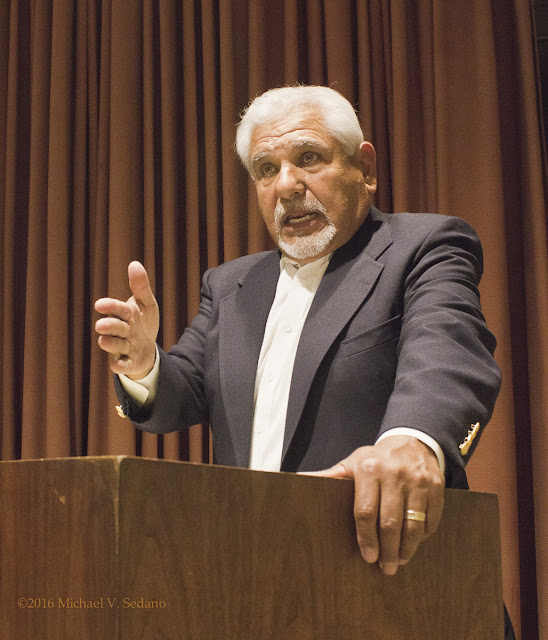

My camera wanted to go Pasadena, but my heart took me instead to Altadena, where Daniel Castro was leading a discussion of a PBS documentary, Latino Americans: 500 Years of History. Episode 5, Prejudice and Pride 1965-1980.

That was a grand decision on my part, not only for the entertaining documentary but for the delightful surprise that cropped up. Sancho has a book!

Southern Californians enjoyed years of “The Sancho Show” on Pasadena City College’s FM radio station, KPCC. Sancho had consejos for young listeners: go to school, study, groove to good sounds, stay out of trouble. Then KPCC went private and the station went to the dogs. The programmers dumped Sancho, the European Hour, and a midnight jazz program, under the guise that, as their star deejay whined, “we want to play our music” emphasis on the “our.”

As I took my seat in Altadena Library’s community room, I noticed poet Mario Angel Escobar seated near the wall. I threw him a head nod and turned attention to the film and discussion. That was when the delightful surprise hit me.

Escobar is a publisher. Izote Press’ book, Dear Chavela, was authored by Sancho, who in his non-radio persona is Dr. Daniel Castro, retired now but formerly president of LA Trade-Technical College, where he met Mario. Escobar related the story, and it’s as wonderfully heart-warming as Dear Chavela, and reflects the raison d’être of Dear Chavela and Castro’s mission as an educator and as Sancho.

Escobar was being arrested on the campus of LA Trade Tech, after a fist fight. Castro intervened, directing the campus cop to release the plumbing student into the president’s custody. Escobar explained his frustration at flunking his plumbing classes. Castro told the kid to explore something different, entonces.

Mario enrolled in philosophy and literature classes and excelled. He got his first degree and kept going until he attained a doctorate and has made a career in teaching and writing. Can I get an ¡Ajua! for that?

Izote Press’ Dear Chavela is the richest 52 pages you will read this year, if you order copies. You’ll read it the first time in an hour, then re-read favorites over and over.

A pastiche on advice columns, Chavela is the advice columnist for The Chicano Times, headquartered at Marrano Beach, California. Chavela is the world’s foremost authority on cosas Chicana, hence the letters.

In his introduction, Castro promises “My goal was to make you, my friends, smile, think, and dream a little. You may laugh, ponder, get angry agree or disagree, maybe even cry—but the goal is to get you thinking.” Promises made, promises kept.

Castro captures the colloquial voice of young people like the ones you grew up with. I heard my own voice, that of my primas and primos, tias and tios, in the epistolary style.

The kid who doesn’t speak Spanish when “everyone” expects that and gets to wondering, “what am I?”

The kid whose name is mispronounced, or denied by anglo teachers in favor of a nickname. The kid asks, “who am I?”

There’s a laugh-out-loud piece on nicknames and their origins.

There’s a tear-jerker piece on the assimilated kid named Brandon Swartz who gets confronted by cultura when his unknown-to-him grandfather dies in Morenci, where his mother comes from. At home, she calls him “son” but in Arizona he’s “mi’jo.” Like the kid with the Mexican names, Brandon asks, “who am I? What am I?”

Each of the thirty-two pieces in the volume runs a few paragraphs, a page or two at most. Many of Castro’s voices are young--elementary and junior high—making Dear Chavela totally appropriate for kids that age. Any reader coming out of the bicultural experience will find a lot to enjoy in this book.

All proceeds from sales go to Castro’s memorial scholarship named for Castro’s son, Quetzalcoatl, who died in an automobile accident.

Click here for a video and information on The Sancho Show and CDs.

Click here for Izote Press and to order copies of Dear Chavela.

Fire, Friends and Fun on Olympic Blvd

I lost track of time and when my wife called me away from writing, I grabbed nothing and headed to the car. We had seats at Cal Tech for the Escher Quartet with guitarist Jason Vieaux. A fabulous concert indeed, yet I had time to remember my camera, but did not. Chamber Music listeners will enjoy The Coleman Concert series at Cal Tech. It’s the best—without exception—music bargain in California. The Eroica Trio wraps the season in April, followed by the $15,000 competition for chamber performers.

There was a host of artists attending. Margaret Garcia, who is learning glass work, was there with LA Art News publisher Kathi Milligan. Polaroid Image Transer artist Mario Trillo and cartoonist Sergio Hernandez joined writer Angel Guerrero in the house. Poet Gloria Enedina Alvarez and artist José Lozano, whose book Little Chanclas is earning him lots of attention, also joined the audience.

The heart of the studio is Jaime’s glass blowing studio. After a successful funding drive, Jaime bought the equipment housed in the loading dock of the industrial building. Guerrero will train young people in the generally inaccessible technology, in addition to Jaime’s own stupendous work.

Guests stationed themselves along the rail above the work floor. Guerrero’s students worked with skilled confidence shaping and blowing a glob of molten glass into a sphere. Jaime’s key apprentice, Tyler Straight, guided the younger apprentices through the process. Suddenly a clinking noise told the sad tale; the piece had gone out of control and broke.

Tyler, Jaime announced, has earned an internship at the Corning Glass Works in New York state. That achievement is a clear indicator of the quality instruction and guidance Jaime Guerrero provides, and Tyler’s talent. La Bloga congratulates Tyler on this outstanding first step in a major career in art and technology of glass.

I missed Araceli Silva’s jewelry studio. I remembered Silva’s beadwork displayed at Artemio Rodriguez’ studio years ago and had lost track of her. I still have. A visit to her webpage illustrates new styles, semi-precious mineral work, but no beading. Drat.

Watch La Bloga for news of future events at 3030.

No comments:

Post a Comment