Michael Sedano

Today’s La Bloga-Tuesday column resumes a literary collaboration between Latinopia and La Bloga that Jesus Treviño and I have pursued for several years. We’ve interviewed Rudolfo Anaya, traveled with the Librotraficantes, and documented Living Room Floricantos. Our newest project involved conversations with Alejandro Morales.

I had to suspend my end of the project, owing to illness and injury. Things are better nowadays and I can start catching up with cool stuff, like this project.

Here are Alejandro and Jesus talking about Morales’ highly respected The Brick People, https://vimeo.com/331624761

You’ll find conversations between Treviño and Morales on The Rag Doll Plagues here, https://vimeo.com/338323546.

Morales' collection of stories Little Nation is the subject at this link.

https://vimeo.com/351673579

Follow this link to Michael Sedano’s review of Captain of All These Men of Death, a story of tuberculosis quarantine. https://labloga.blogspot.com/2019/04/spotlighting-chicano-novelist-morales.html For Sedano's review of The Brick People, this link. https://labloga.blogspot.com/2018/08/brick-that-built-pasadena.html

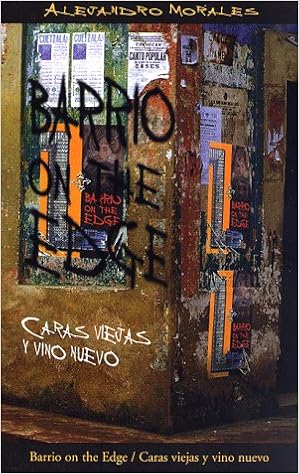

Barrio On The Edge Caras Viejas y Vino Nuevo stands out among United States novels on a number of accounts, not just because it is a Chicano novel with literary significance. Translated from Alejandro Morales’ Spanish by Francisco A. Lomelí, the book, from Bilingual Press, comes in a facing page edition with a critical essay, in English, by Lomelí, and a Morales bibliography.

Barrio On The Edge Caras Viejas y Vino Nuevo stands out among United States novels on a number of accounts, not just because it is a Chicano novel with literary significance. Translated from Alejandro Morales’ Spanish by Francisco A. Lomelí, the book, from Bilingual Press, comes in a facing page edition with a critical essay, in English, by Lomelí, and a Morales bibliography.All that wrap-around material can be a distraction and a buffer against letting the novel speak for itself. Lomelí’s critical piece explains the novel’s authorship, addresses the writerly skills on such magnificent display, and offers a critical lens polished with Chicanidad to focus a reader’s experience.

Barrio On The Edge takes some reading and re-reading, as many an experimental text requires. The experimental style does away with the etiquette of narration, the he saids she saids, the-this-connected-to-that grammar of motives and consequences. Things happen in their own time and as they come to the narrator’s fragmented attention.

The barrio landscape mirrors this narrator’s interior mindscape. The gente who inhabit this barrio live desperate declivitous lives. There’s no nobility nor character-building inspiration available. Junkies and winos are barrio leading citizens. La Virgie plays the anything-goes lubricious sex companion. The Buenrostros are lowlife cruisers who give pachucos a bad name.

If this novel were a film, it’d be a cinema verité hit at artsy film festivals, with discontinuous time, raw sex and ugly domestic violence. This barrio is a landscape painting--by Hieronymous Bosch:

“The earth was red, just right for the production of brick; there were kilns to bake them, individual bricks were stacked up in huge blocks through which jets of fire passed in special tunnels. At night, the kilns resemble monstrous buildings with mouths spewing flames, as if wanting to set the world on fire. The many rows of wooden racks were extremely long, and at night they were transformed by the red glow of the kilns into human shelves whose arms, before baking the damp red bricks, held the reddish gold, the workers’ dreams.”

Readers won’t have a smooth and easy time with the novel, not its people nor its realism, and especially without all narrative etiquette. “Who said that?” disorientation leads to leafing back to the start of a segment and keeping a mental list of who’s doing what to whom and what the hell is wrong with these people?

And there’s nothing wrong with them, that’s the point of being on the edge. Situationality and history place people at the foot of the brick factory. Time can pass them by and they’ll never know it, or someone like Mateo will go with the flow and eventually make it, out there, beyond the edge.

The 1998 edition, Lomelí explains, reprints Morales’ first novel. Caras Viejas Y Vino Nuevo is the first Chicano novel published in Mexico. Morales could not find a United States publisher who wanted to go with a Chicano writer experimenting like William F. Burroughs but without the purple-assed baboons and in Spanish. Lastima. Bilingual Press Editorial Bilngüe launched the edition as the tenth in its Clásicos Chicanos/Chicano Classics series.

2 comments:

Dear Bloga folks: I want to express my appreciation for the review of our book "Barrio on the Edge", a translation of Alejandro Morales' "Caras viejas y vino nuevo". I found some insightful commentary which highlights the relevance of such a novel, particularly (although you didn't say it) because his novel initiated what I'v coined as a "hard-core" novel mainly found among Chicanos since l975. I also wanted to point out that some of the illustrations in the inside of the book are actual photographs of graffiti from Montebello where the action takes place. I actually walked around markets, alleys & other places to photograph what people were expressing anonymously on walls & fences. I provided the publisher with such details to perhaps better represent that barrio world, so it was not meant to be a distraction. Also the little figure which is used to separate narrative fragments is something I found on a wall, which can be interpreted (maybe in more than one way) as "the barrio is everywhere", or it can be left to one's interpretation, which makes it that much more interesting. Thanks, & I thought this might help understand how the translation came about. Saludos to all, Francisco A. Lomelí

Oops, it should state "hard-core barrio novel". Somehow I left out the word barrio although it can be assumed. Best, F.A.L.

Post a Comment