Daniel Cano

Note: Some fight to keep our stories out of our schools. We must fight to keep them in. Dedicated to the teachers fighting the "good" fight.

|

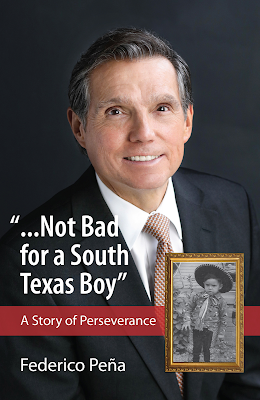

| Bart and Pearl Carrillo, smiling towards the future |

Bart Carrillo’s father, Santos

Carrillo, was born in 1899 in Moyahua, Zacatecas and came to the U.S. in 1915.

"My dad went back to Mexico,"

Bart said, "to fight for Pancho Villa."

In Mexico, Santos met Inez Medina, also of Moyahua, and soon after, they

married and started a family. The fighting between rebel and federal forces

intensified, so Santos and Inez--along with thousands of other

Mexicans--decided to leave Mexico and move permanently to the U.S., joining a

great wave of Mexican immigrants north.

Santos worked in Arizona taking whatever job he could find. "My dad

dug holes, worked the mines, and picked vegetables and fruit,” Bart said.

"When my dad got to Sawtelle (today’s West Los Angeles), he heard they

needed workers out by the Veterans Cemetery.”

He chuckled as he told me how his dad, Santos, who spoke no English,

showed up early one morning at the job site looking for work. The supervisor,

probably wanting to get rid of him, asked if he could pour concrete and lay a

cement sidewalk.

"My dad didn't know the first thing about cement work. He never

learned, but he needed a job."

“Yes,” Santos answered. The supervisor handed him a trowel, and said, "Show me." The Anglo workers stopped to watch. Santos stooped

down into the cement, turning the trowel different ways, figuring how it

worked. He started slapping awkwardly at the wet cement. Everybody went wild

with laughter. Santos got up to leave, but the supervisor called him back and hired

him on the spot. Bart said, “I guess the boss figured if my dad had the guts to

humiliate himself like that, he could make a good worker.”

Santos didn't know it at the time, but he was helping lay the first

sidewalks for what was to become the Westwood Village. Still, Santos’ dream was

to one day be his own boss.

Pearl Pino Carrillo, a bright smile on her face, said her father,

Alejandro Pino, was born on Oct 9, 1900, in Peticato, Sonora, in northern

Mexico. When he was nineteen years old, Alejandro left Mexico and moved to Arizona searching for work. There he met

Carmela Arujo, the girl he’d one day marry. However, looking for better job

opportunities, Alejandro moved from Arizona to L.A.’s westside, a little town

known as Sawtelle.

Pearl said that her maternal grandfather, Feliciano, worked quite a few

years in Arizona for a man named A. J. Stoner. When Stoner left Arizona to open

Sawtelle Lumber at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Cotner Avenue, he

invited Feliciano to move his family out west and work in the lumberyard.

Feliciano agreed. The family settled in, Carmela and Alejandro found each other,

and rekindled their relationship, eventually marrying at St. Sebastian Church

in 1922, and six years later, 1928, Pearl was born in the Sawtelle family home.

J. Stoner went on to become an important developer in Sawtelle, and the

town would name a park and street in his honor, ironically, the same street

where Bart and Pearl would purchase their last home.

|

| Stoner Park, the Japanese Garden |

WWII was heating up. Bart and Pearl were dating. Just before he joined

the Navy, Bart asked his dad if he would go ask Mr. Pino for Pearl’s hand in

marriage. "That's how it was done in those days, an arrangement between

the fathers."

After visiting, what seemed like all day, with Pearl’s father, Bart’s

dad, Santos, returned home. Bart was wild with anticipation, but his father

didn't say anything. Finally, Bart, unable to control himself, asked

his dad, "What happened?"

Santos

told Bart that Mr. Pino needed two weeks to think about it. Bart didn't

understand. What was there to think

about? Bart and Pearl had already been dating.

The two families had known each other for years. Still, Bart knew better than

to question adults. The two weeks seemed like months. After the second week passed, and his dad still said nothing, Bart reluctantly approached him again.

"Oh, yeah," his dad said, casually, "Mr. Pino said

fine."

The long delay confused Bart. It wasn’t until years later his father

told him, laughing, that Pearl's dad had given his blessing the same day Santos

Carrillo had asked. The two men figured they'd make the kids sweat it out a

little.

After a stint in the navy on a destroyer, the Dale, Bart returned home.

He and Pearl began working at boring jobs, Bart gardening, a trade he’d learned

before the Navy. Like his father, Bart couldn't see himself working for anybody

else. So, he and his father went into business with a relative who lived in Tijuana. After the war,

Tijuana boomed, catering to American tourists and servicemen from San Diego.

The Carrillos opened a curio shop,

selling souvenirs to tourists.

Bart loved it, the bargaining, the socializing, and the feeling of being

self-employed. As a Chicano who spoke English and Spanish, Bart liked haggling

over prices with his fellow Yankees, who always believed they were getting the

best price. Bart laughed, “My dad would give me the rock bottom price of an

item, and I'd take it from there. We always made money, no matter how little we

sold it for.”

The Carrillos opened two more stores. Bart, his father, and relative

were putting in a lot of hours each day, working hard to bring in the inventory

and sell it as quickly as possible.

Bart said, “But oh man, the drive from West L.A. to Tijuana was getting

to be too much.”

This was before the 405 Freeway cut through Orange County, and the drive

to Tijuana along the Coast Highway could take up to five hours. “I didn’t like

leaving Pearl

at home alone all that time. It was a really hard time.”

Bart said American tourists flooded the border town. The competition

with other curio shops in TJ increased. Bart realized he couldn’t keep the

business up for too much longer, so he talked his father into selling and

taking the money and investing in a tavern in Santa Monica, an idea he’d had for some time.

His dad agreed.

The Carrillos opened Tijuanita,

a tavern on Main Street

and Pico Boulevard,

in the heart of Santa Monica,

across from the Memorial Auditorium, known for its boxing

cartels. Inez and Pearl

cooked. Santos

and Bart brought in the customers. Pearl

took care of the paperwork. After boxing matches, the Memorial Auditorium

provided a constant flow hungry men and women, sometimes up until midnight and

even to the early morning hours. Chicanos crammed the neighborhood. On

weekends, everyone came to Ocean

Park to attend the concerts

and dances at the Aragon Ballroom.

My father once said of Tijuanita,

“Bart’s mom made the best menudo in

town. On weekends the line was so

long people couldn't even get in.”

The young couple decided to move from West L.A. and buy a home in Santa

Monica, the first of twelve Westside homes they’d come to own. It was in an

Anglo area, far from her family in Sawtelle.

Pearl said, “After we bought the house, we couldn’t even afford a

refrigerator, a stove, or any furniture. I felt alone. I didn’t like the area

because I felt like we were so far away from Sawtelle where all of my family

and friends lived. Five miles was like a hundred in those days.”

Bart and his father began

investing in real estate, rental property. “Oh, what a headache,” Bart said. “I

lost a lot if sleep during that time.”

Rather than sell the family home in Sawtelle, Bart and his father

decided to rent it, Bart recalled, “…to a gringo family.” After some months,

the renters stopped sending the rent payments. “The guy just refused,” Bart

said.

Months went by and still no rent money arrived. Santos and Bart decided

they couldn’t go to the police or courts. The law moved slowly. They didn't want

to threaten the man and make the situation worse.

Bart said, “The guy was always complaining about simple repairs, so we

figured he wasn't very handy with tools. One night we sneaked in and

disconnected the water heater. It was winter and cold. I guess, he didn't know

how to reconnect the pipes, and he couldn't call us because he owed us so much

money. After a few weeks of cold water, he moved out, just like that. You

always had to be using your head."

Customers crowded Tijuanita.

Inez Carrillo added new foods to the menu. Always the businessman, Bart knew he

had to move the restaurant to a bigger place. He wanted to stay in Santa Monica. He knew the

importance of a good location. The wrong move could mean disaster.

He found a perfect building on the eastern part of Santa Monica, on Pico

Boulevard, a main street for thousands of people visiting the beaches on

weekends.

The mid-1950s…. The Bundy Theater was just up the street. Every Saturday

and Sunday evening, people leaving the movies and bars filled Pico Boulevard. The

Korean War was stirring. Three shifts of workers from Douglas Aircraft Co. on

Ocean Park Boulevard, just blocks from Carrillo's Restaurant, guaranteed that

workers packed the restaurant at all hours.

Carrillo’s, along with Casa Escobar, began to attract customers from all

over the Westside, including Brentwood and Beverly Hills. Americans had

discovered tacos and enchiladas. Bart worked over-time catering to the

customers’ needs, but he also anticipated a change in the area.

With all the wars ending, Douglas Aircraft downsized. Gone were

the round-the-clock shifts. The government tore down the Bundy Theater to make

way for the new Santa Monica freeway. Other Mexican restaurants set up shop

along Pico Boulevard and the Westside.

Juan Escobar had firmly established his Casa Escobar in Westwood as the Mexican choice for the more upper

crust clientele--the fur coat, suit-and-tie crowd. Outdoor attendants were

needed to park the luxury cars that pulled up to the restaurant doors.

It didn’t take Bart long to recognize the lull in his business. He knew

he needed to change. Assisted by his brother Carmen, a contractor, Bart

remodeled the restaurant, complete with dance floor, tables, Mexican arches,

and upholstered booths. Business picked up. The Westside population and income

levels soared. Bart's restaurant began to cater to a solid middle-class

clientele.

The skyrocketing property values in Santa Monica and WLA began to

reverberate through the Westside, and since Bart didn’t own the property where his restaurant was located, he knew, to survive, he would have to buy his

own property.

Bart found a perfect lot up the street from his restaurant, but he’d

also heard the owner had already rejected numerous offers to sell. Desperate,

Bart met with the owner, who also owned the Rexall Drug Store nearby. Bart explained his predicament. To Bart's surprise, the man agreed to sell. Bart's

landlord became infuriated because he had already tried to buy the lot.

This gave Bart some leverage. If the owner of the property where

Carrillos was located demanded an unreasonable increase in rent, Bart would

simply pull his business and build again on his own property. Bart and the

landlord negotiated a new ten-year lease at a fair price. As Bart told me, “One

that I could live with.”

He said it worked out because he didn't want to invest the money and time

to build a new restaurant if he didn’t have to. He also began thinking it

didn’t make sense making mortgage payments on the vacant land, so he sold his

lot on Pico for a decent profit to a local realtor.

It wasn’t until later, Bart found out that McDonald’s was interested in

the lot. It was to be one of the first McDonald’s on the Westside. "I had

no idea how much that land was really worth," he said. "Mistakes

happen, and I've made my share." He smiled at Pearl. "That was a big one.”

The ten-year lease on his restaurant passed quickly. In the late 1970s, Westside

real estate skyrocketed. His rent jumped from $700 to $6,000. He had no choice

but to turn off the lights on his beloved restaurant. Though, he said, "I

was getting tired of all the work and staying so late every night."

As Bart and Pearl

told me their life story, they both spoke contentedly, not that everything had

been easy. They had experienced difficult, trying times as well. Still, the

Carrillos considered themselves among a special group of pioneers who

introduced the modern version of Mexican culture, not just food, to the

Westside.

Bart said one of the things of which he was most proud was having hired

many workers, young and old, from both sides of the border, men and women of

various ages and ethnic groups. Of those who came from Mexico, he

encouraged and assisted in helping with citizenship or residency. He helped them buy their first homes and send

their children to school. He talked about many of his ex-employees who today

own businesses. Many of their children have gone to college and entered

respected professions.

After Bart closed his restaurant, he invested in a number of smaller

fast-food restaurants, which he opened in shopping centers and malls throughout

the Westside and Los Angeles.

Again, his businesses flourished, but by the 1990s, he realized that it was all

too much an emotional and financial strain. He sold his restaurants and

settled into a comfortable retirement.

In 1998, they sold their Rancho Park

home, their pride and joy.

"We designed and built that house. We lived there for thirty-five

years, and it's where we raised our children," Pearl said. She showed me photos of a

two-story house, its modernist architecture reminiscent of Frank Geary's work.

Bart said, to keep busy, he spends some hours doing gardening at one of

his son’s businesses. He told me, “Right back where I started.” Pearl laughed.