Still looking for gifts? How about a new book written by one of the founders of La Bloga? He launches his work on December 7. Details below.

The world's longest-established Chicana Chicano, Latina Latino literary blog.

Friday, November 29, 2024

New and Just in Time

Thursday, November 28, 2024

Chicanonautica: Ghost of a Guajolote Day Past

by Ernest Hogan

Uh-oh. Chicanonautica has landed on Thanksgiving again. I should really do something, but what? Been doing this for a long time. Should I do Aztec rituals? Decolonizing the holiday? Food?

Maybe that’s the answer. Rather than repeat myself, I could go back and provide a link to one of my old columns!

So, here's a golden oldie/blast from the past. Way back in 2011. Seems like another world, don’t it? It’s called “Guajolote, Thanksgiving, and Other Words.” Some rasquache, literary riffs, and Chicano weirdness.

Also, I looked it up, “border” in Nahuatl is tlalnamicoyan.

Enjoy the feast. Make your sacrifices.

Ernest Hogan is thankful for being the Father of Chicano Science Fiction. His latest book is Guerrilla Mural of a Siren's Song: 15 Gonzo Science Fiction Stories.

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

The Hero Twins and the Magic of Song

The Hero Twins and the Magic of Song

(Tales of the Feathered Serpent #2)

Written by David Bowles

Illustrated by Charlene Bowles

Publisher: Lee & Low Books; Standard Edition

Language: English

Paperback: 80 pages

ISBN-10: 1947627694

ISBN-13: 978-1947627697

Reading age: 8 - 12 years

Grade level: 3 - 7

In the age when Maya demigods lived among us, two carefree brothers, One Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu, are foolishly lured to Xibalba, the Land of the Dead, to play a game. Unfortunately, it was a one-way trip. Unable to return to the sea-ringed world above, One Hunahpu’s firstborn sons must be raised by their grandmother.

Yet all hope is not lost. Down in Xibalba, One Hunahpu meets the rebellious Lady Blood, and their love leads to another set of twin sons, destined to save their father and uncle and restore balance to the cosmos. But won’t be easy! Lady Blood is shunned in the world above, and the twins are taunted by their half-brothers’ cruel pranks. If they choose to use a little trickster magic, maybe… just maybe… they might succeed.

Adapted from author David Bowles’s retellings and translations of essential pre-Columbian texts like the Popol Vuh, the Tales of the Feathered Serpent series bring Indigenous Mesoamerican stories alive for young readers!

Los héroes gemelos y la magia de la canción

(Leyendas de la serpiente emplumada #2)

En esta novela gráfica que reinventa un cuento indígena mexicano, los gemelos semidioses usan la magia de la canción para rescatar a su padre y a su tío de la peligrosa tierra de los muertos. Una aventura suprema de grado medio!

In this graphic novel retelling of an Indigenous Mexican tale, demigod twins must use their magic of song to rescue their father and uncle from the perilous Land of the Dead. A supreme middle-grade adventure!

En la época en que los semidioses mayas vivían entre nosotros, dos hermanos despreocupados, Uno Hunahpu y Siete Hunahpu, son atraídos a Xibalbá, la Tierra de los Muertos, para jugar. Desafortunadamente, fue un viaje sin regreso. Incapaces de regresar al mundo rodeado de mar, los hijos primogénitos de Uno Hunahpu deben ser criados por su abuela.

Sin embargo, no toda esperanza está perdida. En Xibalbá, Uno Hunahpu conoce a la rebelde Lady Blood, y su amor conduce a otro par de hijos gemelos, destinados a salvar a su padre y a su tío y restaurar el equilibrio del cosmos. ¡Pero no será fácil! Lady Blood es rechazada en el mundo de arriba, y los gemelos se burlan de las crueles bromas de sus medio hermanos. Si eligen usar un poco de magia engañosa, tal vez… sólo tal vez… puedan tener éxito.

Adaptada de los recuentos y traducciones del autor David Bowles de textos precolombinos esenciales como el Popol Vuh, la serie Cuentos de la serpiente emplumada da vida a las historias indígenas mesoamericanas para los lectores jóvenes.

David Bowles is a Mexican American author from south Texas, where he teaches at the University of Texas Río Grande Valley. He has written several award-winning titles, most notably The Smoking Mirror and They Call Me Güero. His graphic novels include the Clockwork Curandera trilogy and the Tales of the Feathered Serpent series, based on stories from his critically acclaimed Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky. His work has also been published in multiple anthologies, plus venues such as The New York Times, School Library Journal, Strange Horizons, English Journal, Rattle, Translation Review, and the Journal of Children's Literature. In 2017, David was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters. He is online at davidbowles.us and on Twitter at @DavidOBowles.

Charlene Bowles is a comic artist and illustrator based in Texas. She graduated from The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley in 2018. Rise of the Halfling King is her debut graphic novel and her work has also been featured on the covers of the award-winning Garza Twins books. She is currently developing many of her own comic projects.

Tuesday, November 26, 2024

The Gluten-free Chicano's Basic Caldo de Pollo

Caldo de Pollo / Chicken Soup With Rice

In November's gusty gale I will flop my flippy tail

And spout hot soup-I'll be a whale!

Spouting once, spouting twice

Spouting chicken soup with rice

Cien años no dura el mal

Escúchame esta esta receta

Que aquí te vengo a cantar ah ah ah

"Caldo de Pollo," by Felipe Barrientos / Luis Manuel Lozano PenaPerformed by Grupo Mojado (YouTube link)

|

This soup has bones. Diners pick out or spit out the bones, not a |

There's a lot of pollo chunks on a roasted bird so The Gluten-free Chicano saved the taco leftovers with the meaty bones and wings not made into tacos. All of this gets boiled down and becomes the pollo part of the caldo. Nota bene: you can boil down the carcass with onion and garlic then strain or pull out the bones to make a rich broth in which you boil the veggies.

Chicken bones from a grocery-store roasted pollo - .06g per lbPotatoes - 15g per papa (white or red)Carrots - 8g per cup, boiledCelery - 4g per cup rawTomato - 4g eachTomato sauce - 6g 8oz canOnion - 10g large bulbGarlic - 1g per cloveCilantro - .7 per sprigComino (seed preferably, powdered good too) - per tsp 1g / 2g seedSalt - 0gBlack peppercorns (ground is just fine) - 1g per tspRice - 45g cup cookedWater

Friday, November 22, 2024

Poetry Connection: Connecting with Young People

Melinda Palacio, Santa Barbara Poet Laureate

Last week, I had the pleasure of being the Emcee for the Poetry Out Loud competition. Most of the students were from Righetti High School and the program was held at the Santa Maria County building. Teacher Krissy Kurth does a wonderful job preparing the students for the competition. Although I am often called on judge poetry contests, I was glad I wasn’t a judge this time; the competition was tough. Poetry Out Loud is different because the students recite a well-known poem. Student Kohen Ross was the runner up for her recitation of Love Song by Dorothy Parker. Three of Santa Barbara’s past Poet Laureates: David Starkey, Chryss Yost, and Perie Longo served as judges and named Alicia Blanco, who recited From the Sky by Sara Abou Rashed, the winner. All three judges felt that Alicia Blanco truly understood the poem and assignment.

Poetry Out Loud helps high school students learn about poetry through memorization and performance. It was nice to see the camaraderie between the participants. Hannah Rubalcava served as prompter, someone who is at ready to give the students the next line in case they forget. Recitation from memory is such a brave act. I was pulling for every student. The county winners will compete virtually at the California Poetry Out Loud State Finals and have a chance to compete in the national competition. The state champion receives a $200 cash prize and all-expense-paid trip to Washington, D.C., $500 for their school to purchase literary materials, and an opportunity to compete at National Finals for college scholarship funds.

Young creatives also showed their talents at the 2024 Annual Teen Arts Mentorship Exhibition. I was pleased to see poetry represented as an art medium. Two categories were represented: Expressive Figure Drawing with mentors Austin Raymond and Chiara Corbo and Creative Expression with Typewriters with mentor Simon Kiefer. All Santa Barbara County high school students ages 13-18 are eligible to apply to one or more mentorships in their area.

If you’ve been to the farmers market or First Thursdays downtown, you’ve probably seen Simon Kiefer offering impromptu on-demand poetry. Simon has spent the last ten years using typewriters to facilitate creative self-expression and community building. In the South County Mentorship with Simon, students used vintage typewriters to express themselves with poetry and creative writing and added a visual element to their words. Student participants included Alex Ortiz, Heidi Sanchez Marquez, and 16-year-old Elsie Sneddon.

Elsie Sneddon happens to be my neighbor and the daughter of City Councilmember Kristen Sneddon. Thanks to the Arts Fund and their Teen Arts Mentorship Exhibition at the Community Gallery in La Cumbre Plaza, I was able to see her poems transposed into works of art. This week’s poetry connection features three new poems by Elsie Sneddon.

Garden Song

Elsie Sneddon

The great wide sidewise seam

like the split of a melon

The boys I love will smash them against the edge of the sink

and picture the flesh that stumbles from them to the floor is caked with the stink and the bees that all live in their abdomens

People think they don't live in me too

but they don't know that I have to be quiet because of the deafening buzz

I stay hungry;

imagine my stomach all scooped out,

feel the knocking of my gut-bell hard against the rind

Peel

Elsie Sneddon

I peel the skin back and find tiny cities there-

the places where you brushed against my temple all have hardened

What does it take to discover you

over and over and over

and to feel the pins of all your tiny lights?

Your dead end honey

touch me lovely

put my face plate in its place

This drawer

the milk you bound

it doesn't burn me now

The debt of pleasure

next endeavor

finding something new to sever

come on cry

releasing something shy and

dirty

I am hurting

I still never

feel enough to feel

half of the things

I have the power to.

Road Dream

Elsie Sneddon

I kept trying to sleep but heat lightning danced behind my eyes

and then I fell:

in my dream I was almost windblown enough to be a shell

a hull of some great ship

blown by electricity

and then I was a husk

of corn

and all my kernels rotted

and my precious teeth fell out

and the inbred dogs ate them,

my pearly whites down their gullets

Creaking down the steps inside a house where no one lives

I etch my face into the countryside and I don't know just how to move

And sometimes nothing's right

and always so much is missing

but sometimes I look into the grass and I don't say a thing and so I looked into the grass and smiled and I just sat there thinking

that if I called this place home

I'd find it hard not to believe in something

Elsie Sneddon is a musician and artist who enjoys learning new things and experimenting with different creative outlets. She especially loves writing, singing, playing, and recording music under the name "Golden Teeth." She is new to sharing her poetry, and her poetic work is currently being showcased for the first time at the Arts Fund Community Gallery.

*an earlier version of this column appears in the Santa Barbara Independent

Thursday, November 21, 2024

Say "Katowiche" in Spanish

It's our last day in Amsterdam, an okay city, clean streets, nice people, sights to see, etc. etc. Oh, then there are the marijuana cafes, everywhere, blending in among the other shops. My wife and I want to visit one, just to see. We walk inside. It’s 1:00 P.M., the people inside are cool, a few blonde Rastas, men in business suits, a pretty normal crowd, all sitting around in chairs and couches, talking, and toking up, suave, como sin nada, just another day in the Netherlands.

It’s the early

2000s. Back in California, sick people hadn’t yet started turning to medical

marijuana, Amsterdam is way ahead of its time, all these people getting loaded,

legally. My wife wants a souvenir, to try later, so she buys a marijuana cookie,

a big ass cookie, chocolate chip. Neither of us had done “yesca” in years, a cookie,

I think, lightweight, not like smoking herb.

That evening,

about 6:00 P.M., we catch the train to Poland, our destination Krakow. We have

to travel across Germany to get there, about an eight-hour train ride. It’s winter,

January and cold, like Arctic cold. A few hours later, we’re out of the Netherlands

and cross into Deutschland, and those images of my dad’s generation, at war,

come flooding to me. It’s dark outside. I try to get some sleep, and, in no time,

I’m out.

I am

awakened by my wife shaking me. She wants soup, and to stretch a little, so she

says she’s heading to the dining car. She didn’t want me to wake up and find

her gone, the stuff of an Agatha Christie novel, a boomer Chicana disappears on

the train to Krakow, not a bad plotline. I don’t’ know, maybe a half-hour later, I hear a conductor

coming down the aisle, saying, “Passports,” in a weird English-Deutch accent.

A

disconcerting idea comes to me -- the cookie! Is pot legal in Germany? I don’t

think so. What do I know about it? What if he asks to check our bags and finds the dope? Panic!

Without giving it much thought, I reach into my wife’s travel bag, take out the

cookie (it’s bigger than I remember), and shove it into my mouth, taking hefty bites,

at the same time, imagining my wife and me in a German jail. I swallow, hard,

and, with my tongue, clear chocolate chips, and any green remnants of “mota” off

my teeth. The conductor enters our cabin.

“Gute

Nacht,” he says, which sounds like, “Goot Nihten,” and he asks for the

passports. I tell him my wife is in the dining car. I hand him both passports. He

checks them and gives something like a friendly salute, and he walks away. I sit

back, my heart pumping, but relieved.

When my

wife returns, I tell her what happened. I thought she’d be impressed by my

quick thinking, smart, and, maybe, heroic, saving us from years in a Nazi

prison camp. She says, in a questioning tone, “You’re kidding. You ate the

whole thing?”

“Yeah,

right, all of it. I had to.”

“You didn’t

save me half, at least?”

“Save you

half? That half could get us time in jail. I don’t know if ‘weed’ is legal in

Germany. We’d be transporting illegal drugs across international borders. How

do I know. I couldn’t take a chance.”

“I'm sure, so, you

ate it all. Come on.”

“It’s just a

cookie. You aren’t missing much. How strong can it be?”

A couple of

hours later, she asks, “Anything?”

“Naw. I

told you. It’s just a cookie, probably weak homegrown, anyway.”

As we enter the train station in Berlin, she says she’s going to the bathroom. It seems like no more than a few minutes. I hear a mechanical voice make the announcement, “Berlin.” My head feels really light, but kind of panicky, you know, how marijuana plays with your head during “blastoff.” I know we don’t have to get down from the train, so I sit tight. I hear loud voices, like echoing in my brain. Uh-oh. Coming up the aisle are two big German cops, blonde, of course blonde, in uniforms, Gestapo style. Anyway, that’s how they look in my fizzling mind. They open the cabin doors and look inside. It’s 1944, at least, that’s how I’m feeling. No, no. I’m cool. “Orale,” I don’t say it, but I think it, to calm myself.

One cop smiles and says, “Gute Nacht.” Did I say these dudes were big. I hear World War II raging outside, the sounds of those Nazi police sirens coming to get you. One guy holds the leash to an enormous German shepherd. I respond, my voice quaking, “Hello, good night.” The dog sticks his massive head into the cabin and sniffs. Stay away from my lips, dog. One guy looks around, surveying our bags. He nods, smiles, and continues up the aisle.

My wife

returns. I describe the scene, the Nazis and all. It isn’t coming out right.

She laughs. “You’re stoned.” She tells

me to sit back and rest. In my head, every sound reverberates and echoes. More

time passes. I can’t keep my conversation straight. I laugh a lot. My wife

shakes her head. Finally, somebody says we’re nearing Katowiche, where we’ll

take a short break. “Katowiche,” I ask my wife? “Is that Polish for Krakow, sure

sounds it?”

“I don’t

know,” she says. “Maybe you should go outside and ask.”

All these

thoughts go through my head, like are we on the right train. She points to a kiosk

and says I should ask there. I put on my jacket. It’s a gale outside. My North

Face won’t protect me from the blast of frost outside. It’s like stepping into

an ice box. It’s late. When I reach it, the kiosk is closed. People gather

around, also wondering if they’re in the right place. It's like the Tower of Babel, everyone speaking different languages. We all stare up at the

large train schedules hanging from the ceilings. I check to see our train

number and destination. It's in Polish. I don't know Polish.

After a

while, mesmerized by the exotic names. I turn, once again, to look at station name. Katowice. My wife comes up next to me. “What happened to you? You’ve been out here

twenty-minutes. Is everything okay?”

“Yeah,” I

answer. “Say Katowiche, but pronounce it, Katoweeche, like Spanish, melodic. It’s a cool

name, right, Katoweeche. Sounds Indian.”

“You’re

stoned.”

“No,

really.” I tell her to say it. “It’s got a soothing sound, Katoweeche.”

She shakes

her head, but says, “Katoweeche. Yes, it is kind of nice. Now, come on.”

“I told

you, see.”

“Well, are

we okay, on the right train?”

“I don’t

know. Look at that sign. It’s all in polish.” The more I look at it, the more

the big sign looks like a mural. I think it's beautiful lettering, a masterpiece, a Posada, except no calaveras.

She looks

up at the sign. In a minute she finds our train number, destination, Krakow,

and estimated time of arrival. “We’re fine,” she says, takes me by the arm and

leads me back towards the train. “Come on. Let’s get inside before we freeze.”

“Yeah, that chocolate chip cookie was strong, man.”

The rest of

our trip is uneventful. We pull into the Krakow train station. It’s old,

stained white tiles on the walls exiting the station tunnel. It’s like we’re in East

L.A, grungy but with style. Our driver doesn’t speak English. We don’t speak Polish. We point to the name

of our hotel from a card. He doesn’t read English, either. It works out. He

finds a taxi driver who reads English.

Oh, a couple of days later, my wife got caught in a snowstorm coming from the only Mexican restaurant in the Krakow, the only place she would eat dinner, each night. She isn’t a sausage fan. This night, I passed. The snow fell, burying the signs she followed back to the hotel. She walked in circles, and in her panic, she forgot the name of our hotel. Long story short, eventually, somehow, she found her way back, shivering, standing at the door to our hotel room, trying to explain what happened, looking disheveled, like she’d gotten the worst of the cold drift, like she’d just had a hit of a chocolate chip cookie. "Welcome home," was all I said.

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

RACING AT DEVIL’S BRIDGE AND OTHER STORIES / CARRERAS EN EL PUENTE DE DIABLO Y OTROS CUENTOS

Spanish translation by Alaíde Ventura Medina

ISBN: 979-8-89375-003-4

Format: Trade Paperback

Pages: 129

Imprint: Piñata Books

Ages: 8-12

Spooky creatures from Latin American lore lurk in these entertaining stories for young people.

In the title story, a boy breaks his mom’s rule against staying out after dark because he is intent on training for the big state track meet. When his younger sister turns up and challenges him to a race across Devil’s Bridge, he taunts her—but is ultimately stunned when she beats him. But more shocking is the sudden appearance of a terrifying figure sporting a goat’s head and wielding a rusty ax!

The stories in Xavier Garza’s new collection feature creepy creatures from Latin American lore with a contemporary twist. There’s Christina, who the bullies dub “Donkey Lady” because of her odd-sounding laughter, but who later terrifies her abusers—and gets the last laugh! Joaquín’s grandfather has been told to vacate his property so the border wall can be built across it, but an Aztec eagle refuses to let the authorities kick the old man off his land. Vince and Marina find an old Ouija board under their dead grandmother’s bed and when a malevolent spirit springs from the game, the old woman’s infamous flying chancla appears to send the demon packing!

Accompanied by the author’s striking illustrations of chupacabras and other monsters, the blood-curdling stories in this bilingual collection for kids ages 8-12 are sure to lure even the most reluctant readers into its pages.

Other Books in the Series

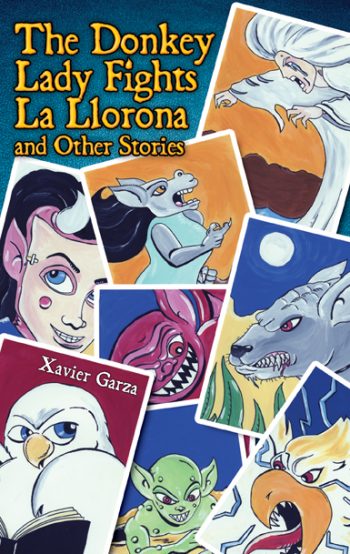

THE DONKEY LADY FIGHTS LA LLORONA AND OTHER STORIES / LA SEÑORA ASNO SE ENFRENTA A LA LLORONA Y OTROS CUENTOS

Margarito is eleven years old now and he’s way past believing in Grandpa Ventura’s ghost stories, but he loves listening to them anyway. One evening on his way home from his grandfather’s, Margarito finds himself alone in the gathering dusk, crossing a narrow bridge. Suddenly, a woman in white floats towards him and calls, “Come to me, child … come to me!” He frantically hides in the shallow river, but soon sees a pair of yellow, glowing eyes swimming towards him. Before long, the Donkey Lady and La Llorona are circling each other, fighting to claim poor Margarito as their next victim!

Popular storyteller Xavier Garza returns with another collection of eerie tales full of creepy creatures from Mexican-American lore. There are duendes, bald, green-skinned brutes with sharp teeth; thunderbirds, giant, pterodactyl-like things that discharge electricity from their wings during thunderstorms; and blood-sucking beasts that drain every single drop of blood from their victims’ bodies!

Set in contemporary times, Garza’s young protagonists deal with much more than just the supernatural: there are chupacabras and drug dealers, witches and bullies, a jealous cousin and the devil. Accompanied by the author’s dramatic black and white illustrations, the short, blood-curdling stories in this bilingual collection for ages 8 – 12 are sure to bewitch a whole new generation of young people.

KID CYCLONE FIGHTS THE DEVIL AND OTHER STORIES / KID CICLÓN SE ENFRENTA A EL DIABLO Y OTROS CUENTOS

Cousins Maya and Vincent are thrilled to be ring side at a lucha libre match. Kid Cyclone, the wrestling world’s favorite hero who also happens to be the kids’ beloved uncle, is facing off against a devil-masked opponent, El Diablo. “No masked devil can beat my uncle. Not even the real devil himself,” declares Maya. But the real devil doesn’t take kindly to such disrespect, and soon Kid Cyclone finds himself fighting the most hellish challenger of all!

Popular kids’ book author Xavier Garza returns with another collection of stories featuring spooky characters from Mexican-American folklore. There’s a witch that takes the shape of a snake in order to poison and punish those who disregard her warnings; green-skinned, red-eyed creatures called chupacabras that suck the blood from wild pigs, but would just as soon suck the blood from a human who has lost his way in the night; a young girl disfigured in a fire set by a scorned lover who gets her revenge as the Donkey Lady; and the Elmendorf Beast, said to have the head of a wolf with skin so thick it’s impervious to shotgun blasts.

Accompanied by the author’s striking illustrations of the creepy creatures, the hair-raising stories in this bilingual collection for kids ages 8 – 12 are sure to lure even the most reluctant readers into its pages.

XAVIER GARZA is the author of numerous books for young people, including The Donkey Lady Fights La Llorona and Other Stories / La señora Asno se enfrenta a La Llorona y otros cuentos (Piñata Books, 2015) and six volumes in the Monster Fighter Mystery series / Serie Exterminador de monstruos. He lives with his family in San Antonio, Texas.

Tuesday, November 19, 2024

Guest Review: Earth, Breath, Light, Corazon Emplumado

Guest Reviewer: Lisbeth Coiman. Earth, Breath, Light, Corazon Emplumado Healing Ancient Wounds, by Jorge Montaño. La Raiz Magazine, October 15, 2024.

Reading Earth, Breath, Light, Corazon Emplumado by Jorge Montaño turned to be an immersion course in Aztec culture. Part Nahuatl, part Spanish, mostly in English, Jorge Montaño’s most recent poetry collection will take the reader through a spiritual journey across urban Los Angeles into the ancestral lands of the Aztecs.

Jorge Montaño is a Chicano poet from Pacoima, CA. As the byline of his Instagram account indicates, “Le canto a lo que florece,” Montaño is inspired by the concept of xochitl and cuicatl, flor y canto, which is Nahuatl for artistic expression. In 2022, he received La Raiz Poetry Prize for his poem “Sangre Indígena.”

La Raiz Magazine is a community-based, literary journal located in San Jose, CA. It publishes multilingual poetry and visual art. Under Elizabeth Montelongo’s leadership, La Raiz Press chose Earth, Breath, Light, Corazon Emplumado as their debut poetry collection. It was the perfect choice. In Earth, Breath, Light …, Jorge Montaño brings gorgeous visual imagery of Aztec culture to life in poems that are both healing and defiant, magical and funny, all wrapped in exquisite cover art, now a signature of La Raiz publications.

With the willowing smoke of copalero the speaker invokes the gods: Huehuetotl, Coatlicue, Cuetzpalin, Chalchiutlicue. When the feathered serpent “calls upon the west,” the speaker shows how to keep going one day at the time until the last dance with Ozomatli. Earth, Breath, and Light is where urban Chicanism meets Aztec cosmology, where the dignity of the Pachuco is proclaimed in Nahuatl.

Earth, Breath and Light requires active reading to decode both the ancient and colonizer’s vocabulary: xochitl, huitzitl, coatl, miquiztli, mazatl, tonalli, tochtli, ozomatli, copalero, chavalitos, justicia, antepasados. Once the reader steps into the fascinating ancient symbols they become participants in the spiritual experience and the subtle humor.

Poems become revelations and at times a joke on the reader. Montaño plays with language in a way that he makes the reader believe the poem will lead to a spiritual revelation, when in fact it leads right to a rock band.

Jorge Montaño’s wisdom shows in Earth, Breath and Light like divine dust: ”love consults not with fear but flirts with the sacrifice of self.” The woman is at the center of this wisdom, whether in the ancestral Aztec symbols “rooted deep inside her precious garden of Huitzlampa” sprinkled in Nahuatl throughout the collection or in the urban references of Chicanism, “La Catrina gazing out the windows of metallic fire,” “the fragrance of earth mother,” in Van Nuys. This woman is sensual and loving but can lure into death. She “calls us to resurrect.” She is flower and hummingbird, a warrior goddess, healing ancient wounds.

That’s the power of this brief collection. It educates us in Mesoamerican Ancestry while it stands against colonialism,

“And we too rise.

We have remembered our names.

We have heard the wind.

It says to resist.”

I hope you love Earth, Breath, Light Corazon Emplumado as much as I do.

Link to publisher: https://rootsartistregistry.com/laraiz.html

About the Guest Reviewer:

Lisbeth Coiman is a Southern California poet and a valued panelist in the notable Writing from Our Immigrant Hearts (link) touring venues across California. La Bloga will share the panel's upcoming readings, venues, and dates.