|

| The new Medellin |

Cartagena, Colombia,

April 19, 2025

Saturday

Time was passing

quickly. I started on this journey nearly ten days ago, on the 11th

of April, starting in Medellin, famed city of unwanted popular drug lore, or as people say, "Medellin, before and after Escobar. From Medellin, to smaller towns and coffee plantations, I’m ending in this old city, Cartagena, one of the first trading centers of

merchandise and humans in the Americas.

Yesterday, my

traveling companions and I visited San Baslio de Palenque, founded in the early

sixteen hundreds by rebellious runaway slaves who fought the Spaniards, faced

executions and extermination, but fought hard, eventually, failing to surrender, won their freedom. Their

descendants still reside in the town, the oldest settlement in the Americas

founded and managed by former slaves, with its own rules and citizen police

force. The people were kind, danced, played music, offered us a tasty lunch, and a curandero blessed the remainder of our trip.

My friends and I

had spent a couple of days in Santa Marta, the second oldest settlement in

South America, where I learned, after reading through a short brochure, Simon

Bolivar had died at a friend’s sugar plantation while waiting to be exiled to

Europe. I was feeling a bit under the weather, decided to pass on a sailing

trip with my friends, and made a pilgrimage to Bolivar’s death bed, instead,

for me, a moving scene, and the sight of a beautiful memorial.

Bolivar had

attempted and accomplished military feats no one thought possible, crossing the

Andes with his soldiers and animals, numerous times, to defeat his enemies and

win independence for what he called El Gran Colombia, today the

countries of Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, and Bolivia, which he hoped to unite, as one, under a strong central government, arguing, only then could Latin America match the power of Europe and the United States.

It was now 5:15

P.M., I stepped out into the heat of Cartagena, a cool breeze blowing in off

the Caribbean. My hotel was right behind the cathedral and a few blocks from

the city’s ancient walls, much like the walled cities in Spain. I knew Gabriel Garcia

Marquez had worked on a newspaper in Cartagena, in his youth, wrote, was

branded a socialist, and fled to Mexico, none of it as easily or wholly

accurate, I’m sure, as I just stated.

I googled his

name, wondering where he might have worked. The first point to appear was his

love of Cartagena, which he chose as his final resting place, at the claustro

de la merced in the University of Cartagena. I could have kicked myself for not

checking earlier. I figured the university would either be closed now, for sure

tomorrow, Easter Sunday, or it would be a long ride from my hotel. Such are the ways of the

brain, but rather than surrender, I left no stone unturned.

I turned to a man

whose horse and carriage were parked a few feet from me. “Excuse me, do you

know where the university of Cartagena is located? I’m looking for the claustro

de la merced.” He looked at me as if I were joking. He leaned forward and

pointed up the street. “Three blocks,” he said, “across from the wall.” It was

now nearing 5:30. I knew it closed at 6:00, but would it even be open Easter

eve? I thanked the man and quickly made the three blocks in a few minutes, the

heat pushing in like a warm foam around me.

It was an

interesting gothic building, nothing spectacular, the usual spires and

decorations around the doors and windows. A man in a uniform stood at the door.

I asked if it was open. He said it was but only for another twenty-five minutes.

He pointed to door leading to a bookstore. I entered and asked the entry fee. The young

woman told me it was free. I entered the claustro, a lot like many monasteries

and church yards I’d seen in Spain and Latin America, quiet, solemn place of

meditation.

In the center of

the courtyard was a statue to Garcia Marquez and an engraving indicating it was

both his and his wife, Mercedes Pardo’s final resting place, where they wished

their ashes to remain. A large scroll covered the walls and told Garcia

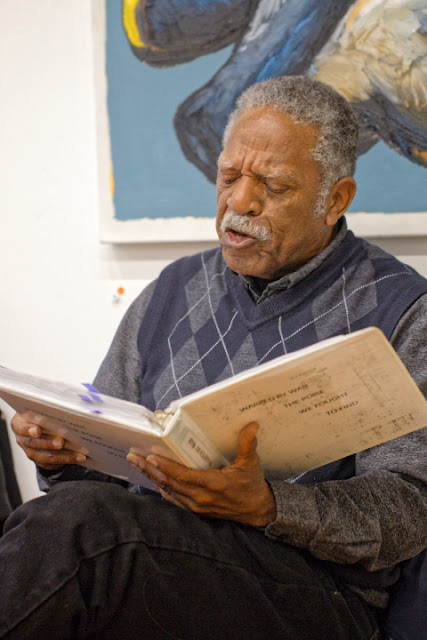

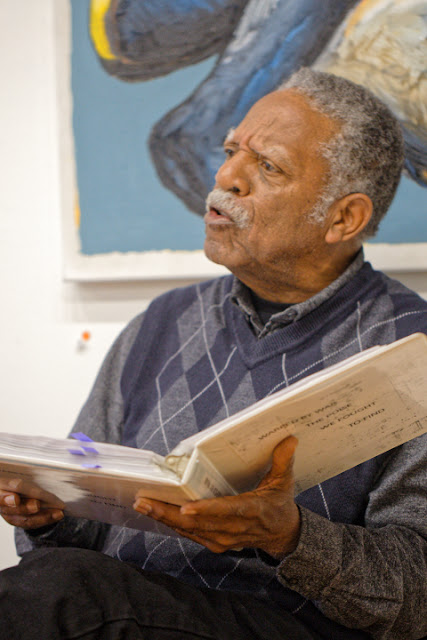

Maquez’s story, from his birth, his schooling, to his days as a young reporter,

his first published literary works, up until his monster tome, One Hundred

Years of Solitude, which changed his life.

Truth be told, I

wasn’t a big Gabo fan. I found him difficult to read, his books complex. It took me six months to

get through One Hundred Years of Solitude, the English translation. I remember

reading, feeling completely lost, literally. I had no idea what was going on,

yet, I had to re-read each sentence and each paragraph, not for the difficulty

but for the absolute beauty of the writing, even in English. In a book of his

short stories, I came across "An Old Man with Enormous Wings," as much a sermon as a story, about an angel, a toothless old man with enormous wings, who

drops to earth and is turned into a side show by the people, his owner keeping him in a chicken coup and charging the town a fee to see

him, until one day he musters the strength to fly back to where he came.

For some reason, I kept returning to Garcia Marquez's stories, a mixture of newspaper accounts blended with

elements of fiction, going back to influences of William Faulkner, Camus, and

Mexican Juan Rulfo, among other masters. I took a seat on a bench. I relaxed. My mind wandered. I’d

read Marquez’s autobiography years ago. I considered some of his ideas about

Colombia and the places he’d lived, loved, and experienced watching the destruction caused by the United Fruit Co. I’m not much for

autobiographies. People tend to keep the juiciest parts of their lives to

themselves, careful how much to reveal.

I entered the

bookstore and purchased a copy “No One Writes to the Colonel,” in Spanish. Sixty pages I can handle. It was closing

time. I stepped outside and crossed the street, found a place to sit on the ancient

wall. I looked back at the university and remembered something Gabriel Marquez

had written, something about writers revealing much of themselves in their

work.

Then he mentioned the secrets we all carry, and how those would probably

make the best writing. He said, “Those I will carry to my grave.” I guess he

did.

The sun had fallen, and the light was quickly disappearing.