The world's longest-established Chicana Chicano, Latina Latino literary blog.

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Giving Tuesday: Make A List, Check It Twice

Monday, November 29, 2021

On #GivingTuesday, consider supporting Tía Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore

Tomorrow is GivingTuesday. What is GivingTuesday? It is a global generosity movement that unleashes the power of radical generosity around the world. GivingTuesday was created in 2012 as a simple idea: a day that encourages people to do good. Over the past nine years, this idea has grown into a global movement that inspires hundreds of millions of people to give, collaborate, and celebrate generosity. GivingTuesday strives to build a world in which the catalytic power of generosity is at the heart of the society we build together, unlocking dignity, opportunity, and equity around the globe. GivingTuesday’s global network collaborates year-round to inspire generosity around the world, with a common mission to build a world where generosity is part of everyday life.

On GivingTuesday, consider giving to Tía Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore through donations, purchasing books and other items, or in any other form of support.

Why Tía Chucha’s?

The

Northeast San Fernando Valley has a population of about 500,000 – the size of

the city of Oakland – yet it had no bookstores, art galleries, or full-fledged

cultural spaces until Tía Chucha's opened its doors in 2001. Thankfully,

various local organizations have for decades provided services to address the

many survival needs of a large number of economically insecure families and

individuals in this area. Believing that it is also everyone’s right to explore

and develop their innate creative gifts, Tia Chucha’s founders set out to

correct the historic absence of life-enhancing artistic and literary options

for this sector of the population. Melding vision with conviction, Tia Chucha’s

was created as a space to embrace the equally important artistic development of

our lives as human beings.

Tia Chucha’s began as a café, bookstore and cultural space owned and run by Los Angeles Poet Laureate Luis J. Rodriguez, his wife Trini, and their brother-in-law Enrique Sanchez. In 2003 Luis, along with singer/musicologist Angelica Loa Perez and Xicano Rap artist Victor Mendoza established a next-door sister nonprofit to incorporate a full range of arts workshops. When in 2007 the cultural café and bookstore disbanded as an LLC, it donated its assets, including inventory, shelves, equipment, and more to the nonprofit to carry its mission forward.

Tia Chucha’s cultural center now provides year-round on-site and off-site free or low-cost arts and literacy bilingual intergenerational programming in mural painting, music, dance, writing, visual arts, healing arts sessions (such as reiki healing) and healing/talking circles. Workshops and activities also include Mexica ("Aztec") dance, indigenous cosmology/philosophy, and two weekly open mic nights (one in Spanish, the other in English). It also hosts author readings, film screenings, and art exhibits as well.

So, if you want to “do good” on GivingTuesday, consider Tía Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore as the recipient of your good acts.

Thursday, November 25, 2021

What's in a Name, an Enigma?

|

| "En esta casa nacio Tomas Alva Edison, el 18 de Febrero, 1848" |

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

For All/ Para Todos

By Alejandra Domenzain

Illustrated by Katherine Loh

Translated by Irene Prieto de Coogan

Publisher : Hard Ball Press

Language : English/ Spanish

Paperback : 53 pages

ISBN-10 : 1734493879

ISBN-13 : 978-1734493870

A young girl named Flor and her father are driven to leave their beloved country for the promise of a land called For All. As Dad works long hours for little pay, Flor struggles to find her place and her voice in a new school. With time, she realizes that despite their best efforts, not having the proper immigration papers means her father has to put up with unfairness, and doors will be closed for her. Flor picks up her green pen and writes from the heart about her journey and hopes, then tells the story of other immigrants who have been excluded from "justice for all." She inspires others to speak up and take action out of love for those that have built the country with their labor and dreams, and out of hope that their country can live up to its ideals.

Alejandra Domenzain grew up in Mexico and the United States. She has been an advocate for immigrant workers for over 25 years, and also worked as an elementary school teacher. Currently, she is dedicated to improving workplace health and safety for low wage workers. Alejandra is using her green pen to write books that invite kids to question, dream, and stand up for justice.

Alejandra Domenzain se crió en México y los Estados Unidos. Ha abogado por los trabajadores inmigrantes por más de 20 años y también fue maestra de primaria. Actualmente, se dedica a mejorar la salud y seguridad laboral para los trabajadores de bajos ingresos. Alejandra está usando su pluma verde para escribir libros que invitan a los niños a cuestionar, soñar y defender la justicia.

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

After I Saw That Wall, I Read the Book

Review: Carolina Rivera Escamilla ...after... Los Angeles: World Stage Press, 2015.

Michael Sedano

I’ve found many a delightful book through what I called “guided serendipity.” In the library, for example, you can discover a new author by pulling something off the New Books shelves if the spine or dustjacket catches your eye. That’s how I came across Carolina Rivera Escamilla’s 2015 short story collection, …After…, through guided serendipity.

I was getting a guided tour of Rhett Beavers’ Echo Park hillsides when a bright mural on a wall that is built to the cobbled street makes me think we’re strolling some exotic hillside hamlet in Tuscany. That transcendent moment gets magnified by the mural’s undulating curtain running parallel to street grade, seemingly floating figures, occupied in their own world, stand with their backs to the strolling photographer. I post the foto on Facebook and that’s the serendipity part.

Alfredo de Batuc knows exactly where Rhett and I were walking. On Facebook, de Batuc posts, “This beautiful mural is by my friend Rafael Escamilla on his sister the writer Carolina Rivera's casa.”

A writer. That wall. Clearly, there could be more than meets the eye on that corner, I thought. Facebook put us in contact and shortly after posting the foto, the writer mails me a copy of her book.

Twenty stories and a glossary give the writer the opportunity to cover a lot of territory and time, fogging boundaries between story collection and coming of age novel. But …After… is not a novel but a well-connected set of stories that can be seen as one woman’s life, and ultimately, it’s not a valuable question. The book is subtitled “Short Stories” and that settles that.

Unsettling is what you get. Disarming, too. These emotions happen per individual story, and through concatenation of the stories as a whole. This is a good thing, by the way. For me, the book started with wariness and curiosity. Near the middle of the table of contents, Rivera has a story named “Macario.”

It’s the first I read, curious to see if this is a takeoff on the B. Traven story/movie of the indio who wants to eat a turkey all by himself. “Macario” is one of those what the heck? Experiences. A man spins out a Bocaccioesque story of his life learning a trade, whoring with his employer, meeting his wife. Risqué to dirty, it’s a story told by a father to his girls. Life pulls no punches for the people of …After…

The lead story offers a masterful example of disarming and unsettling. “Alma About Four-Thirty In the Afternoon” feels suspenseful, like a spy story told in the first person. A friend takes a package in hand “Be careful. They need it.” Across town the character goes, by bus, fearing soldiers and searches and getting disappeared.

Rivera explores the relationships between the two friends, across time and in a variety of urban and rural settings, city, university, and home. The two students enjoy performance art on public buses, distributing flyers under the noses of repression. They are revolucionary-lite.

Prepare to be disarmed in a big understated way, and in a writerly masterful way mixing passive and active voice for a lethal laugh from surprise.

“It began at a meeting where some compañeros informed us about the new American buses arriving in the country.... The next day when the buses are put into service, almost all of them are firebombed. They are “very nice” but they do not really have radios and televisions inside.”

The reader is set up for the surprise and a sudden change in how we perceive the prankster,

“After Alma and I empty all the passengers out of one bus, Alma postures herself like an eagle ready to fly, and, facing north with a grenade in hand, she yells angrily, “Reagan, American imperialists, we shit on your brains and stick your dreams of technological superiority up your ass! Don't you remember Vietnam?”

The scene concludes with Alma pulling the pin and the two revolutionary students disappearing into the crowd. Rivera’s moving pretty fast now, this character will end the story armed and walking the street a marked woman.

People who read Chicana Chicano Literature are going to enjoy reading these stories. After that opening war story, there’s a story about a girl’s first period, stories about pregnancy, sex, abuse, abortion, death and burial. Common experiences set against Salvadorean chaos are anything but quotidian events, and that fact keeps a reader unsettled. It’s the same only really different!

And this is not Chicano Literature, where war and revolution are twentieth century events, las Adelitas, romantic corridos, ahai! In El Salvador, war waits around every corner where some rapist or soldier can grab a woman and disappear her. Don’t walk there alone.

Carolina Rivera Escamilla isn’t hitting readers over the head with the danger, nor making cultural differences idiosyncratic. There’s a host of valuable political and cultural information in these stories, as well as what’s been called “literature as equipment for living.” Put yourself in this character’s world. She grows up adapting to whatever is thrown in her path, except the consequences include torture and death. Do what you need and don’t get caught, or leave the country. That makes voting look all the more attractive. GOTV.

Monday, November 22, 2021

_Labios de piedra, Lips of Stone_ poemario por Xánath Caraza

_Labios de piedra, Lips of Stone_ poemario por Xánath Caraza

Labios de piedra, Lips of Stone

verá la luz próximamente y será publicado por The Raving Press. Este poemario bilingüe

fue traducido por la Doctora Sandra Kingery y está prologado por el Dr. Alain

Lawo-Sukam. En marzo de este año publiqué

en la Bloga algunos poemas que nuestros lectores pueden ver aquí

y son parte de este poemario dedicado a la cultura olmeca. Para hacer un pedido por adelantado pueden visitar

la casa editorial

que lo publica. ¡Que la poesía nos salve!

In

Lips of Stone, Xánath Caraza gives voice to the otherwise “silent

sagacity” (“silenciosa

sagacidad”) of ancient Mexican civilizations. In this highly visual collection,

Caraza draws inspiration from the famous Olmec stone sculptures and the

surrounding natural environment. The poet sits on damp earth with the sculptures,

reads to them, speaks with them. One of the stone heads invites “a conversation

about history” and another functions as an “ancestral mirror.” Readers will

simultaneously feel as if they are standing before a ruin and in conversation

with a living being. These sculptures may have lips made of stone, but through

Caraza they continue to speak to us.

—Victoria Livingstone, PhD

Translator

of Pablo Garcia’s Song from the Underworld

To read Xanath Caraza’s latest poetic collection

entitled Labios de Piedra (Lips of Stone), is to go on a guided

archeological expedition through the jungles of the Olmec “city of stone”. In Caraza’s

treatment of the “mother culture”, we find an Olmec civilization that is not

just the first, or the oldest, but still perhaps the most potent and alive; the

one that will outlast all civilizations and render humanity merely a passing

fad as its ceiba trees and jaguar gods continue to infuse the Olmec world with

its silent power and omnipresence. Accompanied by Sandra Kingery’s English

translations, most poems act as crucial pieces of mortar holding up the oldest

Olmec structures of memories lost in the void of forgotten human history, but

with the capacity to whisper to us of its existence once upon a time and

always. Some of those poetic pieces of mortar artifacts manage to transcend a

modest functionality in the construction to form decorations that project

themselves like three-dimensional alto-reliefs depicting Olmec gods and sacred

creatures. Poems like “Of Wind and Stone,” and “Olmec Pyramid” establish the

tone of the language in this collection which harkens back to an ancient past.

But as a counterweight which provides balance, (a common theme in all things

Mesoamerican), “Green Maize,” and “Bloody Twilight” serve to orient the reader

to the fact that the Olmec world still pulsates with life evidenced by how both

end with similar phrasing: “…mother earth gives birth to another cycle,” (Green

Maize), and “…Wake, jaguar gods, now is the time of bloody twilight,” (Bloody

Twilight). Caraza manages to do what few if any archeologists do when exploring

ancient sites: she pierces the veil which stands between the past and present

to offers us a full-textured taste of Olmec civilization and legacy.

—Gabriel Hugo, author of Tenochtitlan Must

Fall

Friday, November 19, 2021

Arte Público Press News and a Dragon Book Event

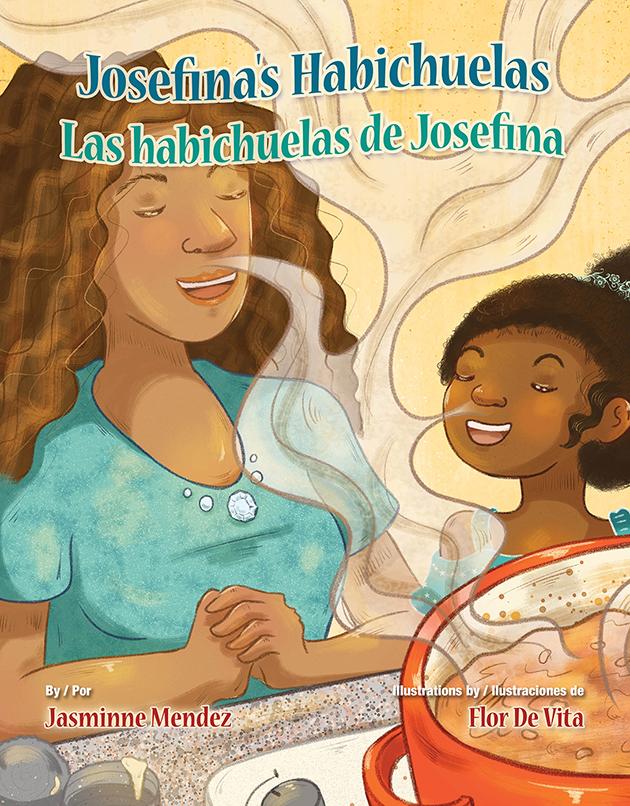

Here's some news from Houston-based Arte Público Press, which just happens to be the publisher of my Gus Corral books. The first piece is an announcement of the winning of an award for Latino Children's Literature by Josefina's Habichuelas/Las habichuelas de Josefina, written by Jasminne Mendez. The announcement also includes some alarming statistics about Latino children's books, and a brief bio of Hermila Lidia Salinas de Alba, for whom the award is named.

The next piece is a notice of Arte Público's end-of-year sale with descriptions of several books in the sale, including Angels in the Wind.

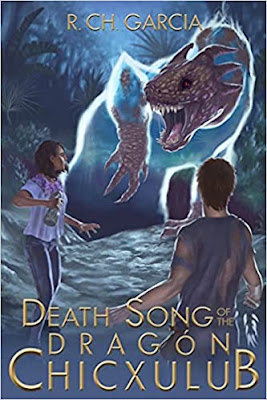

Finally, the info you need to click on a virtual celebration of R. Ch. Garcia's (one of the founders of La Bloga) Death Song of the Dragón Chicxulub.

________________________________

|

|

|

|

|