Review: Alfredo Véa. The Mexican Flyboy. Norman OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2016.

ISBN: 9780806187037

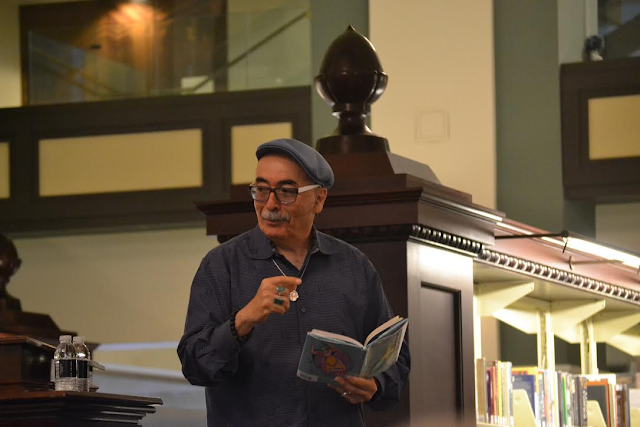

Michael Sedano

The news made me nauseous and when I looked at the photograph my stomach churned. Taggers had spread their filth across one hundred feet of wall that listed the names of missing-in-action or POW Vietnam Veterans. Outraged commenters on social media and in the newspaper concluded the poorly-executed bubble writing was the work of possible groseros ranging from disrespectful punks to thugs whose ignorance cost them a sense of history. The racist fringe yammered for deportation of unknown asshole taggers, sure to be raza in their view. (But then, some these tipas tipos would see us deported for reading while brown.)

The Memorial Day vandalism brought to mind one of the most powerful scenes, in a novel packed with powerful scenes, in Alfredo Véa’s The Mexican Flyboy. Alfredo Véa’s The Mexican Flyboy goes above and beyond what a novel should be, delivering everything readers look for in a novel. The Mexican Flyboy is fun. More importantly, The Mexican Flyboy makes a reader think, and think hard, about history, time, justice, street punks, love, wine, magic, war, communication. It's cool.

By dint of unsurpassed imagination, drudgery work of historical research, plus personal experience, author Véa has crafted a literary masterpiece that deserves to be snapped off the shelves upon its release by University of Oklahoma Press, come June 15, 2016.

Students of the novel, of Chicano Literature, speculative fiction, interpersonal communication, science fiction, viticulturists and oenologists, and the modern school of United States literature, are going to be talking about The Mexican Flyboy for a generation.

Justice doesn’t have time limits, nor does history, in Simon Vegas’ hands, not when he sets his mind to undue miscarriages of justice. He researches lynchings, classical lovers, ancient maps. With accurate data, Simon has the ability to go back in time and make things better and no one's the wiser, except other rescued souls.

Time makes a difference in reading The Mexican Flyboy. The novel packs the kind of complexities that envelop and wrap back upon themselves making for near 340 pages of plot, surprise, revelation, and philosophical conundra. Carry the novel wherever you travel so as to fit-in a page or two when a moment’s down time allows, or to reprise cool stuff you come across, verify an allusion or a twist, let it sidetrack you.

Principally, The Mexican Flyboy’s magic depends on Vegas’ need to turn time back to a defined moment. Arriving physically at the moment say, a kitten dies, or a man is lynched, the time-shifted persona can step in and prevent suffering and death, not by changing events, but by flying the lost souls to a condo in Boca Raton FL.

The Mexican Flyboy is Simon Vegas. He understands time, in his world time flows past current events but always exists in its own dimension concurrent to what’s happening now. Instead of remaining in his own time sphere, Simon reconstructs a device out of time-immemorial, the Antikythera, to go back and pull Ethel and Julius Rosenberg off the death gurney, to yank Joan of Arc off the pyre, to reunite long separated lovers even though they’d maintained a secret love.

Vegas is incapable of undoing properly delivered consequences, like those meted to many of the pintos in San Quentin prison, where Simon delivers some of the novel's most pointed yet surreal sections. Readers will get a kick from Simon reading the riot act via public address to his captive audience. Simon's communication to a diabolical prisoner will hold readers on the edge of their seats.

Much as he wants, Vegas is unable to resurrect his family killed in a stupid accident, nor fix his life subsequent to being orphaned, nor to escape having a hand mangled in a bizarre Vietnam firefight, or probably keep his day job since while he's off rewriting history he's not doing his day job.

He’s fortunate to have Sophia, his wife who lives up to her name, with a baby on the way, and clever friends like the real-life Roberto Cantu, in the role of Hephaestus Segundo, a key scientist who helps Vegas build the functioning Antikythera device.

The most memorable event in Simon’s career revolves around a Chicano in Vietnam, Vegas’ best friend in the platoon. Fulgencio Garza had lived a typical life back on the block. Has teen sex a single time and she gets pregnant. They’re not married but he’s committed to his five year-old son in Port Arthur and would go back and do things right if he could. As the ramp of a helicopter is about to open onto a raging ambush, Garza steps forward regardless of a conviction he will never see the boy again.

Because Fulgencio is killed in the natural course of events, his death lies beyond the antikythera’s influence. Even when, twenty two years later, Simon folds back time to the instant before the NVA round fulfills Fulgencio’s vision, time and magic offer no alternative and Fulgencio dies.

It doesn’t help Simon’s feelings that the maniacal platoon sergeant is shouting “We got fifteen grunts on this chopper, and three or four of them is about to get unlucky. Somebody’s fixin’ to die tonight! Somebody’s fixin’ to go all gray and cold. Somebody’s mama is gonna jerk upright in her bed and feel her son’s last moment on this earth.”(198) None of this will ever change for Simon.

But Simon can take Garza's twenty-two year old son back to that chaotic moment in the helicopter. He's an asshole. A son with contempt for his mother. “She had me, then she went to work and let me watch television and run the streets. She didn’t make me go to school. I don’t remember her ever bein’ home with me. All she ever did was work and cook and . . . cry.” She was crying about the boy's father, who is another object of the mucked up kid's, Fulgencio, Jr.’s, contempt. “Why should I give a shit about him? He didn’t give a shit about me. He died somewhere far away from here a long time ago. He chose to go there.”

Junior, as he’s called, is a total asshole, the kind of kid who would blindly smear his placa across a memorial to Vietnam missing or captured Veterans. Guys like his father. Simon flies him back to that troop bay, just as the rear hatch opens onto the fury of battle. The boy stares into the faces of the men, of his father, leaning into the opening hatch. Véa, a Vietnam infantryman, writes with vivid memories of sight and sound and adrenaline.

“The heavy ramp began to yawn open, and the young troopers in the belly of the aircraft stood up. There was dread and stony resignation in their faces. The sortie didn’t feel right. The world didn’t make sense. This could be the end. There was a loud flurry of cracks and pops just meters from the Chinook. There were a hundred men outside firing their weapons. As the ramp slammed into the ground, the intensity and volume of the gunfire doubled, then tripled into a deafening roar.”

Vegas and Junior watch as Private Fulgencio Garza kisses a small photograph then rises from his seat. With the platoon jumping into the line of fire, tough guy Junior is paralyzed at the profound ignorance of his attitude, the global insignificance of his gangbanging for horse shit values. “They’re gonna stand up and walk out into that? asked Junior. His shattered voice box was emitting sounds of shock. This was no cowardly drive-by shooting. The gunfights in the streets back home in Port Arthur were kids’ games compared to this.” (304)

For pure unmitigated literary power, the next paragraphs will not be matched, where Junior watches the bullet spin out of the bush line, assume its trajectory and Junior screams for it to stop, but it doesn’t, not until it stops in a fine red mist. At that moment, Junior returns to his time and place, prepared for change, to talk to his mother, to open up, to be his father's son. Dad walked out into that.

Add The Mexican Flyboy to the "top of" war literature lists. It stands right next to greats like The Red Badge of Courage, Battle Cry, The Naked and the Dead, Daniel Cano's Shifting Loyalties, and Véa's own Gods Go Begging.

Communication occupies a curious yet important role in the novel. In many ways, the subject of the novel is communication, how people miscommunicate, how they seem bound to play around the edges of meaning and understanding, how they follow assumptions or wildly erroneous misunderstanding, or get played by outside forces.

There’s some profound work packed into The Mexican Flyboy, about communication. The novel drops interesting historical facts—Joan of Arc was found innocent at trial, for example--or bits of knowledge about terroir and fine wine, and lots of other rich detail. That Véa does profound with loud, distracting, often comic, events and incidents, the writing makes the novel so much fun that all that profundity and matter-of-fact knowledge might slip past notice the first time through. Give it a moment, let it sink in then look again. Look it up. Many readers will laugh thinking, “Ah ha! Good one, there, Véa, I didn’t see it the first time.”

More than anything, Alfredo Véa’s version of “what if you could go back in time?” is a speculative fiction gem that helps settle an ongoing controversy among literary critics: the loci among genre and mainstream and literary U.S. fiction. The Mexican Flyboy offers a literary tour de force that erases what boundaries remain. The novel follows a delighting structure, characters emerge from a glimpse in an early page to looming presence in the novel. Some you notice, others come in morsels of surprise. The blend of speculative with historical details tempts readers to look it up in the internet, with a big smile on one’s face, or a quizzical grimace. Reading it engages a reader’s imagination, curiosity, and delight.

I’d like those assholes who tagged the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall to read The Mexican Flyboy. I’d like them to write an essay on Junior’s epiphany for his parents and things which are good. I want those pendejos to think about waiting in the back of that helicopter ready to step into a firefight like the ones that put those names on the wall. Will it save them?

The world's longest-established Chicana Chicano, Latina Latino literary blog.

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Monday, May 30, 2016

Sunday, May 29, 2016

A Chicana Punk Rocker in the 1970s: Alice Bag, Lead Singer for "The Bags" Tells Her Story

Before she was Alice Bag, her name was Alicia Armendariz, growing up in East L.A. It was the 1970s when Alicia was in high school, in love with music, with singing, and with all things artistic. One memorable scene in Alice Bag's memoir, _Violence Girl: East L.A. Rage to Hollywood Stage, a Chicana Punk Story_, is when she writes about an art class she had at Garfield High School. Alicia Armendariz's art teacher noticed her talents and was not only able to get her into an advanced art class, Alice was one of three students asked to design one of the murals for a building on the school's campus. Alice immediately began work designing an Egyptian pyramid. In the end, the criticism she received was not because it wasn't drawn well. Instead, the teacher wanted a pyramid like the ones in Mexico with the addition of cactus and eagles. Alice writes:

"For the rest of that afternoon, I found myself getting angry every time I thought about the mural. I didn't understand why they would give me a wall if they didn't like what I'd done. I didn't understand why Hispanics could only want to be around Mexican pyramid murals. I didn't understand why this white art teacher was telling me what Mexicans like. I love Mexico and Mexican culture, but I didn't want to do the same sort of murals that were everywhere in East L.A.

I realized that I hadn't been chosen because they thought I was a good artist. I'd been chosen because they thought I was a good copier. I turned down the project the next day" (99).

This scene beautifully illustrates a Chicana refusing to be stereotyped and, instead, committed to following her passion. And one of those passions became punk music. Alice then takes the reader on a journey through the 1970s music scene. There are also important chapters interspersed regarding her working class family, her abusive father, the afflictions her father experiences with Diabetes, the attempts at protecting her mother from further abuse, and finally confronting her father.

Alice Bag's memoir is not new. It was published in 2011. I didn't know about it until just recently when a friend from high school, Patricia (Rainone) Morrison, told me about it. Patricia was also a member of the band, "The Bags." Morrison played base. In fact, if you take a look at the back of the book, there is a picture of Patricia with her punk band name, "Trash Bag." Patricia went on to be the bassist for "Sisters of Mercy," "Legal Weapon," "The Damned," and now lives in London. Alice remains in Los Angeles, teaching and writing.

More recently, Alice has published a book of diaries that recount her post-punk days--when she decided to live in Nicaragua in the 1980s. The book is entitled, Pipe Bomb for the Soul (2015). In the book, Bag gives us another example of a mujer/Chicana who dared to teach children whose lives were upended in the Nicaraguan/Sandinista war. Of course, as in all travel, one learns more about oneself. Alice comes face to face with her own capitalist, U.S.-raised self. She writes in the epilogue:

"My revolution happened from the inside out over a prolonged period of time. It started with my visit to Nicaragua and continues every day of my life. There's always a news story, a personal interaction, or a provocative idea that requires me to face the world as a teacher/student, that requires me to step outside my comfort zone and engage in praxis" (106).

Alice Bag (Alicia Armendariz) and her two published books illustrate the rich diversity within the Chicana and Chicano community: the "mezcla" of cultures, historical movements, family dynamics, social, psychological, and political struggles. It seems repetitive to say this, but it is still necessary: we are not about cactus, eagles, and Mayan pyramids. Those images have been co-opted and used to define a group. So gracias, Alice Bag! Andale. Keep on writing.

And thank you to Patricia Morrison for this lead. You have and always will be quite the amiga!

Friday, May 27, 2016

Arte Público Fall Catalog

Yes, summer hasn't officially begun yet - I know, I know. But here's the Fall Catalog from one of our favorite publishers (it's at the top of my list.) Never too soon to think about holiday gifts, is it? Or those cold, stormy nights huddled around a cup of hot tea or Mexican chocolate, shared with a warm book? Whatever, the good people at Arte Público Press have assembled an eclectic array of impressive literature for their end-of-year offerings. I'm only too happy to preview the catalog here on La Bloga.

From classic short fiction by a Chicano Lit pioneer to recovering the lost work of a border journalist of the early 20th century to Spanish tongue twisters, there is something for every type of reader in this catalog. The featured titles include bilingual picture books with important life lessons; a retrospective collection of Puerto Rican poetry; best practices to help keep Latino youth out of the criminal justice system; and a look at an urban big city neighborhood from a child's point of view.

And then there's my latest ...

[all content from Arte Público Press]

______________________________________________

My Bad: A Mile High Noir

Manuel Ramos

September 30, 2016

Ex-con Gus Corral is fresh out of jail and intent on keeping his nose clean. He’s living in his sister’s basement, which he shares with a cat or two, Corrine’s CDs and their father’s record collection. The blues music in particular strikes a chord, matching the way he feels about his current state.

Things start to look up when Gus gets a job working as an investigator for his attorney, Luis Móntez. An activist in the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Móntez is slowing down and getting close to retirement, and he figures the felon can do the legwork on his cases. So when María Contreras comes to see the lawyer about her dead husband’s “business partner”—someone she has never heard of who’s demanding his share of the profits of a business she knew nothing about—Móntez has Gus look into the situation.

Narrating the story in alternating chapters, Gus and Luis recount their run-ins with suspicious characters as they learn that there’s more to the case than meets the eye. The widow’s husband owned and operated a local bar, not a Mexican folk art import company called Aztlán Treasures. And word on the street is that he was murdered on his boat in the Sea of Cortez. Soon, the dead bodies are piling up and the pair is surrounded by shadowy figures that point to money laundering, drug smuggling and even Mexican crime cartels.

The follow-up to Desperado, Ramos’ first novel featuring Gus Corral, My Bad races to a walloping conclusion in a Rocky Mountain blizzard, leaving fans of crime novels—and Chicano literature—eagerly awaiting the next installment in his mile-high noir.

Manuel Ramos is the author of numerous books, including Desperado: A Mile High Noir (Arte Público Press, 2013), The Skull of Pancho Villa and Other Stories (Arte Público Press, 2015) and Brown-on- Brown: A Luis Móntez Mystery (University of New Mexico, 2003). He lives in Denver, Colorado.

_____________________________________________

The Wetback and Other Stories

Ron Arias

September 30, 2016

In the title story, Mrs. Rentería shouts, “David is mine!” as she and her neighbors gather around the dead but handsome young man found in the dry riverbed next to their homes in a Los Angeles barrio. “Since when is his name David?” someone asks, and soon everyone is arguing about the mysterious corpse’s name, throwing out suggestions: Luis, Roberto, Antonio, Henry, Enrique, Miguel, Roy, Rafael.

Many of the pieces in this collection take place in a Los Angeles neighborhood that used to be called Frog Town, now known as Elysian Valley. Ron Arias reveals the lives of his Mexican-American community: there’s Eddie Vera, who goes from school yard enforcer to jail bird and finally commando fighting in Central America; a boy named Tom, who chews his nails so incessantly that it leads to painful jalapeño chili treatments, banishment from the neighborhood school and ultimately incarceration in a school for emotionally disturbed kids; and Luisa, a young girl who can’t resist an illicit visit to Don Noriega, an old man the kids call El Mago who is known as a curandero in their neighborhood.

Most of the 14 stories included in this volume were originally published in journals that no longer exist, including El Grito, Caracol and Revista Chicano-Riqueña. Arias was one of the first to use magic realism and connect U.S. Hispanic literature to its more popular, Latin American cousin. This collection finally gathers together and makes available the short fiction of a pioneer in Mexican-American literature.

Ron Arias, a journalist who worked for People magazine for 22 years, is the author of five non-fiction books, including Five Against the Sea (Dutton, 1989), Healing from the Heart with Dr. Mehmet Oz (Dutton, 1998) and White’s Rules: Saving Our Youth One Kid at a Time with Paul D. White (Random House, 2007). He is the author of a foundational Chicano novel, The Road to Tamazunchale (Bilingual Review Press, 1975). He lives with his wife in Hermosa Beach, California.

______________________________________________

Diaspora: Selected and New Poems

Frank Varela

September 30, 2016

“Now that my past is longer than my future, / I feel a diminishment inside my body. / Like in an overcoat, my arms are lost in the vastness of its sleeves.” In “Remembrance,” Frank Varela poignantly writes about the longing for loved ones—Aunt Consuelo, Doña Simona, Don Benacio -- who are all spirits now. He hears them gossiping in the kitchen, sipping coffee and eating pastries. Their ghosts are a comfort, he writes, “So why then do their faces / blur in my memory?”

In this collection of 55 poems, Varela writes about growing up Puerto Rican in Brooklyn, noting that there are two types of Puerto Ricans: “those born on the island, / others like me, / the children of exiles.” Pondering the universal sentiment of immigrant children, he notes that he was considered a spic in the United States and a gringo in the land of his parent’s birth. “All I wanted was the impossible: / To be the who I am in a land / unafraid of the me I have become.”

Like his grandfather who cleared ten acres in Cibuco, Puerto Rico, “to wrench subsistence from red clay,” Varela loves the land and what it provides. “The land is rich with decay and past seasons. / On my best days, I can reach into the soil / and marry my soul with the green world— / tarragon, escarole, lemon balm, sage.” Expressing love and appreciation for his Puerto Rican family and culture, Varela’s poems reflect on the universal joys and pains of everyday life. This collection, which contains a mix of previously published and new poems, offers a survey of the poet’s work from 1988 to the present. Frank Varlea is the author of Serpent Underfoot (March/Abrazo Press, 1993), Bitter Coffee (March/Abrazo Press, 2001) and Caleb’s Exile (Elf Creative Workshop, 2009). He lives and works in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

_______________________________________________

Overcoming Disparity: Latino Young Men and Boys

Edited by Frank Acosta and Henry A.J. Ramos

September 30, 2016

Experts estimate that American taxpayers spend about $75 billion annually to support adult prisoners in detention, most of whom are men of color. Meanwhile, another generation of Latino young men and boys is at risk of being incarcerated.

This wide-ranging collection highlights the best practices developed and employed by community-based institutions to keep low income, at-risk Latino youth out of prison so they can lead productive lives. Focusing on the work of practitioners and organizations, most notably the non-profits Compadres National Network and La Plazita Institute, Overcoming Disparity shares strategies, tools and resources used to effectively deal with the challenges boys of color face because of poverty, injustice and discrimination.

Based on the culturally grounded model called La Cultura Cura, the practices outlined emphasize Chicano/Latino history and use cultural expression and ritual to educate and create self-awareness, develop community programs and advance socially focused business ventures that encourage youth and community economic development.

The editors assert it is imperative that the nation’s fastest-growing community—including millions of impoverished Latino young men and boys—must be successful. Along with a curated sampling of leading tools, models and evaluations, Overcoming Disparity is a critically important text for policy makers, community builders, researchers, investors and

others concerned about American social policy and its impact on the economy and the lives of its citizens.

Frank de Jésus Acosta is the author of The History of Barrios Unidos (Arte Público Press, 2007). Henry A.J. Ramos is the author of The American GI Forum: In Pursuit of the Dream, 1948-1983 (Arte Público Press, 1998). They are the co-editors of Latino Young Men and Boys in Search of Justice (Arte Público Press, 2016).

_______________________________________________

P. Galindo: Obras (in)completas de José Díaz

Edited by Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez

November 30, 2016

Born in 1898 on the southern side of the Río Grande River, José Díaz would go on to become a journalist and poet whose work now illuminates life along the Texas-Mexico border in the first half of the 20th century. His poetry and prose were published in numerous Spanish-language newspapers in Texas—much of it under the pseudonym P. Galindo —beginning in the 1920s.

Díaz wrote with humor about social and political issues, frequently using the “décima,” a type of poetry popular in previous generations. He chronicled the lives of his people, writing about everything from the start of the school year to the effect of the Cold War on the local economy. Of particular interest are his observations on the racism experienced by Mexican Americans during that time. In addition to poetry and journalistic writings,P. Galindo: Obras (in)completas de José Díaz contains riddles, letters and telegrams.

Scholar and editor Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez writes in his introduction that Díaz’s work is notable because he wrote for a literate, Spanish-speaking working class. Published as part of the Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage project, this book introduces students and scholars to the work of an important writer who documented life in South Texas from the Great Depression to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. This is fascinating reading for those interested in the history of the Texas-Mexico border region, Spanish-language newspapers in the United States and their role in the community.

Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez, a full professor and founding faculty member at the University of California, Merced, has written and edited numerous scholarly books and articles on Chicano literature, including The Textual Outlaw: Reading John Rechy in the 21st Century, co-edited with Beth Hernandez-Jason (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, 2015), and With a Book in Their Hands: Chicano/a Readers and Readerships Across the Centuries (University of New Mexico Press, 2014).

________________________________________________

Rooster Joe and the Bully/El Gallo Joe y el abusón

Xavier Garza

October 31, 2016

Still thinking about the possibility of painting with oils and not just kids’ tempera paint, Joe and his best friend Gary see Luis, a chubby sixth grader, running down the hall. Soon they see why he’s running: Martin Corona, the school’s biggest bully, is in hot pursuit. They watch as he slams Luis against the lockers and demands money. Much to his surprise, Joe finds

himself defending Luis. Luckily, the vice principal shows up just in time to rescue both Luis and Joe.

Reluctant to be a tattletale, Joe tries to avoid Martin and his gang. Even though he knows it’s just a matter of time before Martin exacts his revenge, fear doesn’t keep him from going to football games and trying to impress the girl he likes. And when he meets Martin Corona under the bleachers after school one day, it’s a conversation with his Grandpa Jessie about la lucha—or everyone’s individual fight—that helps Joe and his friends not only survive the encounter, but put the bully in his place.

This bilingual “flip” book for intermediate readers also includes Garza’s black and white sketches depicting bullies, heroes and the roosters that Joe loves to draw. Award-winning author and illustrator Xavier Garza once again writes an action-packed novel that will appeal to all young teens.

Xavier Garza is a prolific author, artist and storyteller. His work includes Maximilian & the Mystery of the Guardian Angel (Cinco Puntos Press, 2011), a Pura Belpré Honor Book; Kid Cyclone Fights the Devil and Other Stories / Kid Ciclón se enfrenta a El Diablo y otras historias (Piñata Books, 2010); and The Donkey Lady Fights La Llorona and Other Stories /La señora Asno se enfrenta a la Llorona y otros cuentos (Piñata Books, 2015). He lives with his family in San Antonio, Texas.

_______________________________________________

El torneo de trabalenguas/The Tongue Twister Tournament

Many of the tongue twisters included in this picture book will be familiar to Spanish-speaking children—and their parents too! But the book also includes tried-and-true tongue twisters familiar to English speakers, like “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” With colorful illustrations depicting the unique contestants, this bilingual collection of phrases that are difficult to say quickly will challenge children to excel in both English and Spanish.

Nicolás Kanellos is the Brown Foundation Professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston and founder-director of Arte Público Press. He is the author of numerous books on U.S. Hispanic literature and theatre for adults, including Hispanic Immigrant Literature: El Sueño del Retorno (University of Texas Press, 2011). He practiced these tongue twisters while growing up in New York and Puerto Rico. He lives with his family in Houston, Texas.

Set in a Puerto Rican neighborhood in New York City, this bilingual picture book for children ages 4–8 captures both the daily life of an urban community and a child’s excitement about her birthday surprise. Children will be inspired to look at—and maybe even write about—their own neighborhoods with new eyes.

Virginia Sánchez-Korrol, professor emerita at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, is the author of several books, including Feminist and Abolitionist: The Story of Emilia Casanova (Piñata Books, 2013). She lives in Piermont, New York.

Carolyn Dee Flores is the illustrator of Dale, dale, dale: Una fiesta de números / Hit It, Hit It, Hit It: A Fiesta of Numbers (Piñata Books, 2014) and Canta, Rana, canta / Sing, Froggie, Sing (Piñata Books, 2013), both of which were named to the Texas Library Association’s Tejas Star Reading List. She lives in San Antonio, Texas.

___________________________________________

Later.

Manuel Ramos is the author of several novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction books and articles. His collection of short stories, The Skull of Pancho Villa and Other Stories, was a finalist for the 2016 Colorado Book Award. My Bad: A Mile High Noir is scheduled for publication by Arte Público Press in September, 2016.

From classic short fiction by a Chicano Lit pioneer to recovering the lost work of a border journalist of the early 20th century to Spanish tongue twisters, there is something for every type of reader in this catalog. The featured titles include bilingual picture books with important life lessons; a retrospective collection of Puerto Rican poetry; best practices to help keep Latino youth out of the criminal justice system; and a look at an urban big city neighborhood from a child's point of view.

And then there's my latest ...

[all content from Arte Público Press]

______________________________________________

My Bad: A Mile High Noir

Manuel Ramos

September 30, 2016

A gripping crime novel that brings together an ex-con and his attorney in a case that questions who's really the bad guy.

Ex-con Gus Corral is fresh out of jail and intent on keeping his nose clean. He’s living in his sister’s basement, which he shares with a cat or two, Corrine’s CDs and their father’s record collection. The blues music in particular strikes a chord, matching the way he feels about his current state.

Things start to look up when Gus gets a job working as an investigator for his attorney, Luis Móntez. An activist in the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Móntez is slowing down and getting close to retirement, and he figures the felon can do the legwork on his cases. So when María Contreras comes to see the lawyer about her dead husband’s “business partner”—someone she has never heard of who’s demanding his share of the profits of a business she knew nothing about—Móntez has Gus look into the situation.

Narrating the story in alternating chapters, Gus and Luis recount their run-ins with suspicious characters as they learn that there’s more to the case than meets the eye. The widow’s husband owned and operated a local bar, not a Mexican folk art import company called Aztlán Treasures. And word on the street is that he was murdered on his boat in the Sea of Cortez. Soon, the dead bodies are piling up and the pair is surrounded by shadowy figures that point to money laundering, drug smuggling and even Mexican crime cartels.

The follow-up to Desperado, Ramos’ first novel featuring Gus Corral, My Bad races to a walloping conclusion in a Rocky Mountain blizzard, leaving fans of crime novels—and Chicano literature—eagerly awaiting the next installment in his mile-high noir.

Manuel Ramos is the author of numerous books, including Desperado: A Mile High Noir (Arte Público Press, 2013), The Skull of Pancho Villa and Other Stories (Arte Público Press, 2015) and Brown-on- Brown: A Luis Móntez Mystery (University of New Mexico, 2003). He lives in Denver, Colorado.

_____________________________________________

The Wetback and Other Stories

Ron Arias

September 30, 2016

This collection brings together the short fiction of an acclaimed journalist and Chicano literature pioneer.

In the title story, Mrs. Rentería shouts, “David is mine!” as she and her neighbors gather around the dead but handsome young man found in the dry riverbed next to their homes in a Los Angeles barrio. “Since when is his name David?” someone asks, and soon everyone is arguing about the mysterious corpse’s name, throwing out suggestions: Luis, Roberto, Antonio, Henry, Enrique, Miguel, Roy, Rafael.

Many of the pieces in this collection take place in a Los Angeles neighborhood that used to be called Frog Town, now known as Elysian Valley. Ron Arias reveals the lives of his Mexican-American community: there’s Eddie Vera, who goes from school yard enforcer to jail bird and finally commando fighting in Central America; a boy named Tom, who chews his nails so incessantly that it leads to painful jalapeño chili treatments, banishment from the neighborhood school and ultimately incarceration in a school for emotionally disturbed kids; and Luisa, a young girl who can’t resist an illicit visit to Don Noriega, an old man the kids call El Mago who is known as a curandero in their neighborhood.

Most of the 14 stories included in this volume were originally published in journals that no longer exist, including El Grito, Caracol and Revista Chicano-Riqueña. Arias was one of the first to use magic realism and connect U.S. Hispanic literature to its more popular, Latin American cousin. This collection finally gathers together and makes available the short fiction of a pioneer in Mexican-American literature.

Ron Arias, a journalist who worked for People magazine for 22 years, is the author of five non-fiction books, including Five Against the Sea (Dutton, 1989), Healing from the Heart with Dr. Mehmet Oz (Dutton, 1998) and White’s Rules: Saving Our Youth One Kid at a Time with Paul D. White (Random House, 2007). He is the author of a foundational Chicano novel, The Road to Tamazunchale (Bilingual Review Press, 1975). He lives with his wife in Hermosa Beach, California.

______________________________________________

Diaspora: Selected and New Poems

Frank Varela

September 30, 2016

Puerto Rican poet reflects on identity, life and death in this moving collection.

“Now that my past is longer than my future, / I feel a diminishment inside my body. / Like in an overcoat, my arms are lost in the vastness of its sleeves.” In “Remembrance,” Frank Varela poignantly writes about the longing for loved ones—Aunt Consuelo, Doña Simona, Don Benacio -- who are all spirits now. He hears them gossiping in the kitchen, sipping coffee and eating pastries. Their ghosts are a comfort, he writes, “So why then do their faces / blur in my memory?”

In this collection of 55 poems, Varela writes about growing up Puerto Rican in Brooklyn, noting that there are two types of Puerto Ricans: “those born on the island, / others like me, / the children of exiles.” Pondering the universal sentiment of immigrant children, he notes that he was considered a spic in the United States and a gringo in the land of his parent’s birth. “All I wanted was the impossible: / To be the who I am in a land / unafraid of the me I have become.”

Like his grandfather who cleared ten acres in Cibuco, Puerto Rico, “to wrench subsistence from red clay,” Varela loves the land and what it provides. “The land is rich with decay and past seasons. / On my best days, I can reach into the soil / and marry my soul with the green world— / tarragon, escarole, lemon balm, sage.” Expressing love and appreciation for his Puerto Rican family and culture, Varela’s poems reflect on the universal joys and pains of everyday life. This collection, which contains a mix of previously published and new poems, offers a survey of the poet’s work from 1988 to the present. Frank Varlea is the author of Serpent Underfoot (March/Abrazo Press, 1993), Bitter Coffee (March/Abrazo Press, 2001) and Caleb’s Exile (Elf Creative Workshop, 2009). He lives and works in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

_______________________________________________

Overcoming Disparity: Latino Young Men and Boys

Edited by Frank Acosta and Henry A.J. Ramos

September 30, 2016

Outlines the difficulties faced by Latino young men of color and provides strategies to increase their ability to lead successful lives.

Experts estimate that American taxpayers spend about $75 billion annually to support adult prisoners in detention, most of whom are men of color. Meanwhile, another generation of Latino young men and boys is at risk of being incarcerated.

This wide-ranging collection highlights the best practices developed and employed by community-based institutions to keep low income, at-risk Latino youth out of prison so they can lead productive lives. Focusing on the work of practitioners and organizations, most notably the non-profits Compadres National Network and La Plazita Institute, Overcoming Disparity shares strategies, tools and resources used to effectively deal with the challenges boys of color face because of poverty, injustice and discrimination.

Based on the culturally grounded model called La Cultura Cura, the practices outlined emphasize Chicano/Latino history and use cultural expression and ritual to educate and create self-awareness, develop community programs and advance socially focused business ventures that encourage youth and community economic development.

The editors assert it is imperative that the nation’s fastest-growing community—including millions of impoverished Latino young men and boys—must be successful. Along with a curated sampling of leading tools, models and evaluations, Overcoming Disparity is a critically important text for policy makers, community builders, researchers, investors and

others concerned about American social policy and its impact on the economy and the lives of its citizens.

Frank de Jésus Acosta is the author of The History of Barrios Unidos (Arte Público Press, 2007). Henry A.J. Ramos is the author of The American GI Forum: In Pursuit of the Dream, 1948-1983 (Arte Público Press, 1998). They are the co-editors of Latino Young Men and Boys in Search of Justice (Arte Público Press, 2016).

_______________________________________________

P. Galindo: Obras (in)completas de José Díaz

Edited by Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez

November 30, 2016

This volume recovers the Spanish-language writings of a Mexican-American poet and journalist.

Born in 1898 on the southern side of the Río Grande River, José Díaz would go on to become a journalist and poet whose work now illuminates life along the Texas-Mexico border in the first half of the 20th century. His poetry and prose were published in numerous Spanish-language newspapers in Texas—much of it under the pseudonym P. Galindo —beginning in the 1920s.

Díaz wrote with humor about social and political issues, frequently using the “décima,” a type of poetry popular in previous generations. He chronicled the lives of his people, writing about everything from the start of the school year to the effect of the Cold War on the local economy. Of particular interest are his observations on the racism experienced by Mexican Americans during that time. In addition to poetry and journalistic writings,P. Galindo: Obras (in)completas de José Díaz contains riddles, letters and telegrams.

Scholar and editor Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez writes in his introduction that Díaz’s work is notable because he wrote for a literate, Spanish-speaking working class. Published as part of the Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage project, this book introduces students and scholars to the work of an important writer who documented life in South Texas from the Great Depression to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. This is fascinating reading for those interested in the history of the Texas-Mexico border region, Spanish-language newspapers in the United States and their role in the community.

Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez, a full professor and founding faculty member at the University of California, Merced, has written and edited numerous scholarly books and articles on Chicano literature, including The Textual Outlaw: Reading John Rechy in the 21st Century, co-edited with Beth Hernandez-Jason (Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, 2015), and With a Book in Their Hands: Chicano/a Readers and Readerships Across the Centuries (University of New Mexico Press, 2014).

________________________________________________

Rooster Joe and the Bully/El Gallo Joe y el abusón

Xavier Garza

October 31, 2016

Acclaimed kids' book author returns with an exciting bilingual novel about middle school life.

Joe López is in seventh grade, and he dreams of being an artist as good and successful as his grandfather. He’s thrilled when the new art teacher compliments him on his pencil drawings of roosters and offers to teach him how to paint with oils. She even suggests that he might want to enter his piece in the county fair!

Still thinking about the possibility of painting with oils and not just kids’ tempera paint, Joe and his best friend Gary see Luis, a chubby sixth grader, running down the hall. Soon they see why he’s running: Martin Corona, the school’s biggest bully, is in hot pursuit. They watch as he slams Luis against the lockers and demands money. Much to his surprise, Joe finds

himself defending Luis. Luckily, the vice principal shows up just in time to rescue both Luis and Joe.

Reluctant to be a tattletale, Joe tries to avoid Martin and his gang. Even though he knows it’s just a matter of time before Martin exacts his revenge, fear doesn’t keep him from going to football games and trying to impress the girl he likes. And when he meets Martin Corona under the bleachers after school one day, it’s a conversation with his Grandpa Jessie about la lucha—or everyone’s individual fight—that helps Joe and his friends not only survive the encounter, but put the bully in his place.

This bilingual “flip” book for intermediate readers also includes Garza’s black and white sketches depicting bullies, heroes and the roosters that Joe loves to draw. Award-winning author and illustrator Xavier Garza once again writes an action-packed novel that will appeal to all young teens.

Xavier Garza is a prolific author, artist and storyteller. His work includes Maximilian & the Mystery of the Guardian Angel (Cinco Puntos Press, 2011), a Pura Belpré Honor Book; Kid Cyclone Fights the Devil and Other Stories / Kid Ciclón se enfrenta a El Diablo y otras historias (Piñata Books, 2010); and The Donkey Lady Fights La Llorona and Other Stories /La señora Asno se enfrenta a la Llorona y otros cuentos (Piñata Books, 2015). He lives with his family in San Antonio, Texas.

_______________________________________________

El torneo de trabalenguas/The Tongue Twister Tournament

Nicolás Kanellos - Illustrations by Anne Vega

October 31, 2016

This bilingual picture book features tongue twisters in English and Spanish

“Ladies and gentlemen, girls and boys, doggies, kitties and mousies: Welcome to the grand Tongue Twister Tournament!” And so begins this championship in which the best tongue torturer will win the tongue twister trophy.

The competitors include a variety of quirky characters, including Lengua de Lagarto, or Lizard Tongue, whose tongue is tied “just so.” There’s Grumpy Granny, who raps about a raggedy cat, and El Chupacabras, who loves to eat critters, “even insects are for me / cows and cats and doggies too /chupa chupa chupa cabras, BOO!”

The competitors include a variety of quirky characters, including Lengua de Lagarto, or Lizard Tongue, whose tongue is tied “just so.” There’s Grumpy Granny, who raps about a raggedy cat, and El Chupacabras, who loves to eat critters, “even insects are for me / cows and cats and doggies too /chupa chupa chupa cabras, BOO!”

Many of the tongue twisters included in this picture book will be familiar to Spanish-speaking children—and their parents too! But the book also includes tried-and-true tongue twisters familiar to English speakers, like “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.” With colorful illustrations depicting the unique contestants, this bilingual collection of phrases that are difficult to say quickly will challenge children to excel in both English and Spanish.

Nicolás Kanellos is the Brown Foundation Professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston and founder-director of Arte Público Press. He is the author of numerous books on U.S. Hispanic literature and theatre for adults, including Hispanic Immigrant Literature: El Sueño del Retorno (University of Texas Press, 2011). He practiced these tongue twisters while growing up in New York and Puerto Rico. He lives with his family in Houston, Texas.

Anne Vega is the illustrator of Magda’s Tortillas / Las tortillas de Magda (Piñata Books, 2000) and Magda’s Piñata Magic / Magda y la piñata mágica (Piñata Books, 2001). She lives and works in Columbus, Ohio.

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

A Surprise for Teresita/Una sorpresa para Teresita

Virginia Sánchez-Korrol - Illustrations by Carolyn Dee Flores

November 30, 2016

This bilingual picture book lovingly celebrates family relationships while depicting a Puerto Rican community in New York City.

When Teresita opens her eyes that morning, she knows it’s a special day. It’s her birthday, and now she’s a big girl. She’s seven! And her Tío Ramón has promised her a surprise. She can’t wait to find out what it is!

“Is it time for Tío Ramón to come to our block?” she asks her mamá excitedly as she sits down for breakfast. But it’s too early. Her uncle has to take his snow cone cart to the other blocks before he comes to theirs. All day, Teresita watches for the green and white cart. She listens for Tío Ramón calling, “Snow cones, cold snow cones. ¡Piraguas! ¡Piraguas frías!”

While she waits for her uncle, she jumps rope, plays games with her friends and watches the goings-on in her neighborhood. Mothers hold their young children’s hands as they walk to the corner bodega to buy groceries. Boys ride bikes and play stickball. Older people sit at windows and enjoy the sights and sounds of their community. And coming from far up the block, where water sprays from an open fire hydrant, Teresita finally hears the sound of her uncle’s voice. What will her surprise be?!?

“Is it time for Tío Ramón to come to our block?” she asks her mamá excitedly as she sits down for breakfast. But it’s too early. Her uncle has to take his snow cone cart to the other blocks before he comes to theirs. All day, Teresita watches for the green and white cart. She listens for Tío Ramón calling, “Snow cones, cold snow cones. ¡Piraguas! ¡Piraguas frías!”

While she waits for her uncle, she jumps rope, plays games with her friends and watches the goings-on in her neighborhood. Mothers hold their young children’s hands as they walk to the corner bodega to buy groceries. Boys ride bikes and play stickball. Older people sit at windows and enjoy the sights and sounds of their community. And coming from far up the block, where water sprays from an open fire hydrant, Teresita finally hears the sound of her uncle’s voice. What will her surprise be?!?

Set in a Puerto Rican neighborhood in New York City, this bilingual picture book for children ages 4–8 captures both the daily life of an urban community and a child’s excitement about her birthday surprise. Children will be inspired to look at—and maybe even write about—their own neighborhoods with new eyes.

Virginia Sánchez-Korrol, professor emerita at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, is the author of several books, including Feminist and Abolitionist: The Story of Emilia Casanova (Piñata Books, 2013). She lives in Piermont, New York.

Carolyn Dee Flores is the illustrator of Dale, dale, dale: Una fiesta de números / Hit It, Hit It, Hit It: A Fiesta of Numbers (Piñata Books, 2014) and Canta, Rana, canta / Sing, Froggie, Sing (Piñata Books, 2013), both of which were named to the Texas Library Association’s Tejas Star Reading List. She lives in San Antonio, Texas.

___________________________________________

Later.

Manuel Ramos is the author of several novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction books and articles. His collection of short stories, The Skull of Pancho Villa and Other Stories, was a finalist for the 2016 Colorado Book Award. My Bad: A Mile High Noir is scheduled for publication by Arte Público Press in September, 2016.

Thursday, May 26, 2016

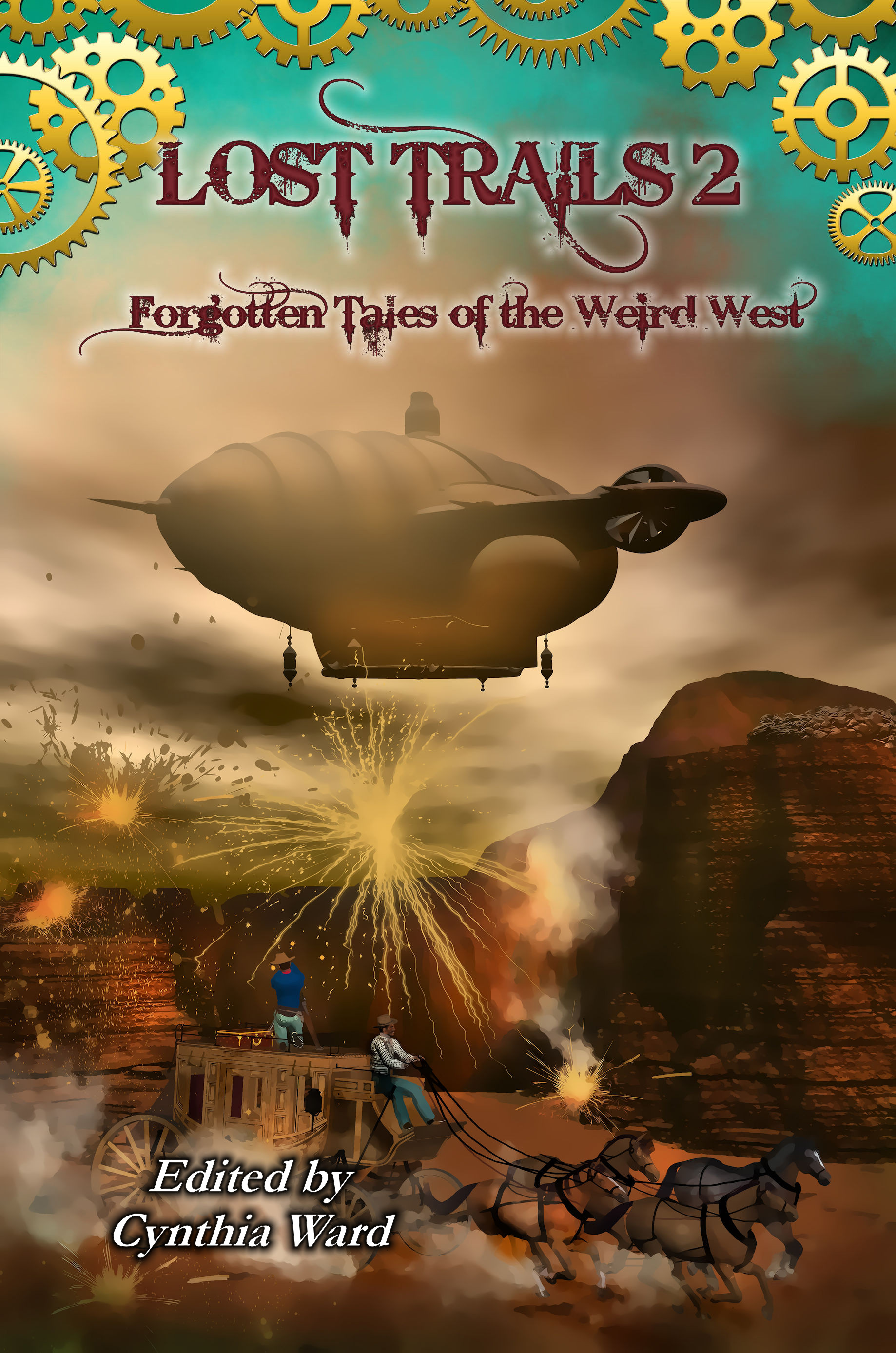

Chicanonautica: Aztlán is the Wild West

by

Ernest Hogan

Oralé,

buckaroos! Lost Trails 2: Forgotten Tales of theWeird West,

edited by Cynthia Ward, with another story by me, plus a lot of other

fantastic rip-snorters by some of the best damn writers around.

It's

a follow-up to the first Lost Trails anthology,

that included my story “Pancho Villa's Flying Circus,” an

anti-steampunk romp that has gained a bit of a reputation.

You

better grab them both if you want to stay on top of things.

This

second volume features “Lupita's Hand,” an Aztláni western with

gunplay and Aztec magic. It was inspired by the travels in Arizona

and New Mexico, searching for my roots. Did I mention that I'm

descended from Irish cowboys and Mexican curanderos? I'm as Wild West

as huevos rancheros, another weird, rasquache product of Aztlán, as

all Chicanos are.

It's

an obsession with me. So much that I find visions of a sequel popping

into my head. Maybe there's a whole world – or even a universe

growing in there, while I gather research materials in the real west.

As

a kid growing up in the fifties and sixties, I absorbed a lot of the

Wild West through popular culture, though I do find Zane Grey and

Louis L'Amour kind of dull. I prefer things like Jodorowsy's El

Topo and Ishmael Reed's Yellow Back Radio Broke Down. I

like my west weird as well as wild.

As

a kid growing up in the fifties and sixties, I absorbed a lot of the

Wild West through popular culture, though I do find Zane Grey and

Louis L'Amour kind of dull. I prefer things like Jodorowsy's El

Topo and Ishmael Reed's Yellow Back Radio Broke Down. I

like my west weird as well as wild.

Mexicans

and Indians help. Spaghetti westerns – my favorite is A Bullet

for the General -- especially when they are bizarre and don't

know it, are great. Just don't let it get all whitebread on you. For

me Aztlán is the Wild West.

You

see, the Wild West isn't history, it's myth, violent dreams spawned

by the struggle to build a life in land snatched through generations

of bloody conflict. Who are we? What are we becoming? Who are we

shooting today?

You

see, the Wild West isn't history, it's myth, violent dreams spawned

by the struggle to build a life in land snatched through generations

of bloody conflict. Who are we? What are we becoming? Who are we

shooting today?

Of

course Hollywood and its corporate masters want to make it all

suitable for Chinese videogame addicts and American tract-housing

dwellers, but there's something about this land and its myths. They

want to be wild. They have issues. And the real history is there:

fermenting under the volcanic landscapes, mongrel ghosts with

mythotecnic agendas that go way back, and reach into the future . . .

It's

time to take back the Wild West, Aztlán, and let it be as weird as

it needs to be.

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Surviving Santiago

By Lyn

Miller-Lachmann

- Hardcover: 320 pages

- Publisher: Running Press Kids (June 2, 2015)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0762456337

- ISBN-13: 978-0762456338

Returning to her homeland of Santiago, Chile, is the last thing

that Tina Aguilar wants to do during the summer of her sixteenth birthday. It

has taken eight years for her to feel comfort and security in America with her

mother and her new husband. And it has been eight years since she has last seen

her father.

Despite insisting on the visit, Tina’s father spends all his

time focused on politics and alcohol rather than connecting with Tina, making

his betrayal from the past continue into the present. Tina attracts the

attention of a mysterious stranger, but the hairpin turns he takes her on may

push her over the edge of truth and discovery.

The tense, final months of the Pinochet regime in 1989 provide

the backdrop for author Lyn Miller-Lachmann’s suspenseful tale of the survival

and redemption of the Aguilar family, first introduced in the critically

acclaimed Gringolandia.

Reviews

"Smooth dialogue, a quick pace, and palpable suspense

combine to make a compelling read. . . . A riveting story of love and

acceptance amid a tumultuous political landscape."

—Kirkus Reviews

"[F]or collections in need of literature with Hispanic

protagonists and historical time periods not often covered in schools."

—School Library Journal

"[I]ntriguingly multilayered."

—Booklist

"While Surviving Santiago is a companion novel to Gringolandia

(Curbstone, 2009), it can be read as a standalone. The setting in Chile creates

a tense atmosphere for this historical fiction novel."

—VOYA

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Dance to the Music, If You Know It.

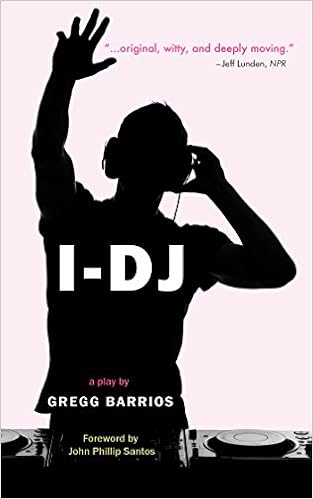

Review: Gregg Barrios. I-DJ. East Brunswick NJ: Hansen Publishing Group, 2016.

ISBN: 978-1-60182- 328-1

ISIN: B01958Z1GU

Michael Sedano

Gregg Barrios’ I-DJ requires a lot more information than I can muster, leaving me a clueless reader unless I do a lot of homework to flesh out the playscript. However, even for a high-information reader, I-DJ is the kind of play that must be experienced on a live stage, not on the page. It would be an impressionistic multimedia tour de force, on stage.

Not that reading I-DJ isn’t a rare pleasure; it is.

Barrios weaves a compelling story across two acts of two scenes each. Chicanidad blends with Hollywood glitter blends with gay lifestyles entangling Warren, the central character in Shakespeare and Shakesqueer, porn, murder, AIDS, the street, rape, sex shows, drugs, hip-hop, disco balls, laser beam light shows, and looking back not with anger but a survivor’s relief.

Reading I-DJ makes me grateful for Google music because, although it’s a lot of work to find it, the music is an essential element to the drama. As Warren announces early in the first scene, “A&M Records –was—IS the fucking soundtrack of my LIFE!”

And the play’s the thing wherein to capture the tenor of Warren’s extended monologues reflecting on his career as actor, artist, and joto, while informing one’s appreciation, or training one’s ear, to the discography of a record label.

Unless the editor missed a typo twice, the play’s second character, DJ, opens the play signing—not singing—a variation on a lyric in the song “God Is A DJ.” DJ plays much of the time in silhouetted miming synchronized with Warren’s speeches. DJ cues vinyl on turntables, flashes album covers, does assorted business. DJ comes into voice now and again speaking counterpoint to Warren’s moods, and as a third character, DJ Mutant. Essentially, I-DJ is a one-man tour de force.

The drama opens with 40 year-old Warren Peace, born Amado Guerrero Paz, reminiscing, celebrating the pinnacle of his life’s journey: landing a role in Ham-a-lot, a gay version of Hamlet. It’s a triumphant moment after a lifetime of some very hard knocks.

Warren relates how he, a Whittier native, finds a niche in glitter Hollywood, how he settles into a career as a personality, an actor whose “day job” is midnight shift disc jockey at the Pair-a-Dice Ballroom, a Hollywood dance club.

The putative hiatus to play the Ham-a-lot role leads Warren to find a replacement DJ. This is the twentysomething character, DJ Silence. Warren challenges DJ to spin music only from the A&M catalog to accompany Warren’s memories; if so, DJ will get a big break, fill-in DJ during Warren’s absence to play Shakesqueer.

The Ham-a-lot role is an elaborate set-up to the history Warren rolls out, from little boy, muy joto his familia says, and loved by a mother and father, and mentored by a colorful aunt, to child actor, to teen hustler, to committed partner, to entrepreneur, to bereaved lover, to top-notch DJ and narrator of his story.

Barrios drops a lot of names, from Terrence McNally to Peter Frampton to a one-and-a-two aging teevee bandleader, to Veronica Lake, as well as performers like Chris Montez, the Carpenters, Cat Stevens. Herb Alpert makes a cameo when the young Warren explains his fascination with A&M music begins when the boy mistakes the Armenian musician for a Mexican hunk pressing his first albums in Warren’s tío’s garage. The error nonetheless gives the young Chicano a sense of hope and identity.

Readers who know the music will find I-DJ a fulfilling read. Folks like me, ignorant of most of the music except hits like “Lonely Bull” or the “Whipped Cream” album from the 60s, will have to do a lot of work to keep up with the fast-paced developments and constantly cued-up sounds.

The two-actor drama requires strong actors to fill the roles. Warren dominates the talking roles, the play is one extended monolog after another. For the DJ role, a patient young man content to play against a dominant central actor.

While the playscript has a 2016 copyright, the play has been produced at least twice. In San Antonio in 2012, Rick Sanchez played DJ Warren Peace and Dominique J. Tijerina DJ Silence / DJ Mutant. In 2014, the play was part of a NY festival, with Sanchez reprising the DJ role and Hunter Wulff carrying the subordinate roles. In April, Barrios and I-DJ were featured at the San Antonio Book Festival.

In an email from Gregg Barrios, he mentions a possible California production this Fall. With the play’s visual effects, pop soundtrack, sympathetic character, I-DJ is too large and too big for a 99-seat house, though it has the feel of an intimate small performance space. Given the Hollywood setting and out-of-town production history favored by the Center Theatre Group, I-DJ would look great on the Mark Taper Main Stage, where the related “Angels In America” played an extended run to adoring audiences. A ver.

I-DJ is both a paperback and e-book available through mail-order organs. Ask your local independent bookseller to bring your copy to the shelves. I-DJ is a fast read initially, then readily re-read and re-read to capture the details and assemble the soundtrack to this modern musical treat.

On the Schedule

La Bloga-Tuesday has a rich line-up of reviews and poetry upcoming in the next weeks. A pair of On-line Floricantos will vie for attention in June with reviews extending through July, including The Mexican Flyboy, Black Dove, Escape from Planet Pleasure, Pariahs-Writing Outside the Margins, Maria's Purgatorio, The Sorrows of Young Alfonso, Breaking Ground Anthology of Puerto Rican Women Writers.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)