Text from Serge's final show at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History:

Sergio Hernandez

Chicano Time Capsule, Nelli Quitoani

January 22 - April 17, 2022

For forty years, the late Chicano artist and cartoonist Sergio Hernandez has echoed important cultural topics and socio-political issues of the Chicano community. Early on, Hernandez began working for “Con Safos Magazine”, the first Chicano literary magazine. Upon being recruited by “Con Safos” member and artist Tony Gomez, Hernandez began to align his practice with themes related to the emerging Chicano Movement or “El Movimiento”. The Chicano Movement was and still is geared toward advocating for “social and political empowerment through “chicanismo”, the idea of taking pride in one’s Mexican-American heritage, or cultural nationalism.”

Across painting, cartoons, and murals, Hernandez satires socio-political happenings and provides an intimate perspective of the Chicano community. Influenced by Chicano culture, iconography, and artists alike, Hernandez’s work became a beacon calling for action and attention to the harsh realities faced by the Chicano community. The artworks in this exhibition are a small yet compelling collection of Hernandez’s contribution to the Chicano art and power movements.

The panel of comic strips on display belong to the “Arnie and Porfi” comic series. Struggling with the duality of his identity as a Mexican- American, Hernandez often battled with his internal desire to adhere to conservative family-views and his newly found chicanismo. Hernandez expressed this conflict through satire and comedic relief through the Arnie and Porfi comics, visualizing the dystopian world. In other words, through art and humor Hernandez exposes the political oddities and disproportionate disparity experienced by Mexican- Americans.

Sergio Hernandez (1948-2021) was born and raised in Los Angeles, California in the South Central area known as the Florence/Firestone District. He received his Bachelor Degree in Chicano Studies from San Fernando Valley State College, which is now known as the California State University, Northridge.

QEPD my friend. See you on the other side. Michael Sedano

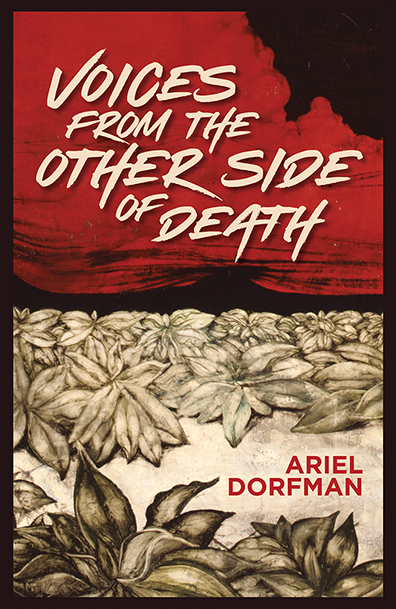

How To Read Voices from the Other Side of Death by Ariel Dorfman

Michael Sedano

Poetry collections give reviewers nightmares. One novel, one review, sabes? A single well-wrought poem will be worth its own essay. Hence, the pesadilla when an anthology comes with the richness and character of Ariel Dorfman’s Voices From The Other Side Of Death, coming this month from Arte Publico.

You should read this book. Caregivers must read this book. People in love ought to read

Dorfman’s as important an author as America produced in the twentieth century. This collection represents a pinnacle in the writer’s career. Indeed, when one detects the author’s authentic voice, it’s an old man who’s scared of dying, hiding behind his characters and imaginative settings.

Starting with the exemplary “How to Read Donald Duck,” Dorfman’s work characterizes itself with clever insouciance masking deadly serious values and revolutionary motives. That’s Voices From The Other Side Of Death, in a nutshell.

This is poetry.

Don’t be fooled that prose poems look like paragraphs. One sentence, spoken by vegetables during harvest, fills an entire page.

There are pages displaying eccentric columnar text, odd and distracting indentations, lots of white space. A casual browser will see that and say “poetry!”

It’s the thoughts that count, it’s the expression, and certain stylistic quirks like a heavy reliance upon Anaphora, repetition, for emphasis. Poetry lovers will really enjoy the author's pastiches on eternal sonnets.

The author may be most familiar to readers in a second-hand way, through grim stage plays and movies about Chilean torturers and desaparecidos. These dramatic vehicles, directed by others, offer a third party’s gloss on the author’s eye. Voices From The Other Side Of Death is Dorfman in his own artist’s voice, if not in propria persona.

That Persona becomes an issue for readers. Is Dorfman the “I”, or “the man” of the narrative? There won’t be much ambiguity his “I” isn’t one of the historical personages of the book’s first set of poems whose motives run a gamut of personages

- Pablo Picasso from the dead has words for Colin Powell who draped Guernica before a speech;

- Christopher Columbus condemns a conquistador for stealing local place names;

- Hammurabi wonders how he, creator of Law, can refrain from cursing Donald Rumsfeld;

- William Blake assembles a litany of allusions for Laura Bush. This piece is unfair, but Laura makes a convenient foil as the face who could have stopped a thousand ships.

- What do you think Salvador Allende is going to bark at Barack Obama?

- James Buchanan, history's worst U.S. president, has some grateful words for Shithead;

- Dante Alighieri speaks to the same name about special places in Hell.

These pieces are Dorfman at his cleverest. Students of the Classics will love that the poems comprise a coherent set of progymnasmata-type exercises in ethepoeia. That's a mouthful, but that's what it is. Writer groups might use the titles as prompts to explore their own creative impulses. This first section provides some fun reading. But after this, for this reader, organization goes all to Hell; it doesn't matter.

Technically, the book presents a section 2 and 3. That’s a linear fact. The pastiches on Cervantes and Shakespeare can be divided out into a wonderful little section of its own.

The heart of this book are four wonderfully eloquent eulogies, “Ashes to Ashes,” “Is There a Place Your Lips Go?,” “Long Forgotten,” and “A Sort of Epilogue with Help from Francisco De Quevedo.” These are distributed among section 2 and 3.

When opening this collection, the title alone screams “willing suspension of disbelief.” A reader has to put aside the coherencies of normal realities to read words purportedly spoken by a man dead 500 years.

There’s supposed to be some distance between the page and the reader, but Dorfman’s arte grows painfully personal in the four death, dying, memory eulogies. These are the thoughts of a poet, facing inevitability, seeking justifications for what comes after a life’s love has died.

The poet holds onto love as hard as possible. He takes his cue from De Quevedo’s 17th century poem, “Amor Constante Más Allá De La Muerte,” and Quevedo’s hyper romantic vision,

Ash they will be, but filled with meaning;

Dust they will be, but dust in love.

Dust is the persona in “Ashes to Ashes.” Human ashes mixing together, one dust reminds the other dust that in life he’d promised, I’d love you beyond death and she didn’t believe him. The poem is the best and most perfect work in the book. Its soulful ethos equals the intensity of the best love poems, in its consumingly joyous conclusion,

she knew that she was not alone, and they embraced, they embraced and seeing you, she knew that he had not lied, she knew that I was telling the truth when I promised that I would love her beyond death.

Shifting pronouns give a poem a way of sneaking up on a reader. As in Ashes, the poem begins in third person, its emotions growing powerfully into expression so heartfelt its expression transcends mere grammar. Love so intense the writer loses his own willing suspension of disbelief and begins speaking from the heart, “he” was always “I”.

Dorfman dedicates the book to Angélica, "who speaks from life." Then he seems to switch gears on the reader. A man tells a woman he’ll love her when they’re both dust, a lifetime’s piropo that becomes a family ritual invocation in the third person. In the first person, she dies from a plague. In his own voice, the author says he’s sentimental thinking that Angélica will be dust, that the finality of death remains somewhere in the future.

As a reader living with Alzheimer’s Dementia, these four elegies for death, dying, and memory, speak for people like us. For the author, his Angélica will be gone, one day and forever after. There’s kindness in that style Death. You live it once. Even the political prisoners in that final set of poems, they die horrible deaths but they die once and finally.

For the likes of us, caregivers living with dementia, our Angélica dies the day a diagnosis on a sheet of foolscap turns into wide-eyed fear at what’s happening before my eyes to my Angélica. And every day after, something happens again, and again, something grows in a concatenation of horrors and hopelessness.

We dementia caregivers will love our Angélicas when we are dust. If we didn’t say it to her when she was still here, Angélica will never know and won’t laugh at my romantic foolishness. That Angélica, she’s gone.

Caregivers, read “Ashes to Ashes” aloud, if only for your own benefit and let your tears flow.

No comments:

Post a Comment