Puccini’s Opera, Madame Butterfly, comes from 1904. It’s as grand a tragedy as Grand Opera produces. Here's LAO’s précis:

Lights, camera, action: An American officer in turn-of-the-century Japan wants a bride, and a greedy marriage broker obliges, assuring him that the union can be easily dissolved. The innocent Cio-Cio-San believes they’re in love, even as Lt. Pinkerton moves on. For three years, she fights off rising debts and new suitors, refusing to believe she’s been abandoned. But when their long-awaited reunion finally arrives, the lieutenant isn’t alone—and he isn’t here for her. End scene. link https://www.laopera.org/performances/2025/madame-butterfly

|

| Orchestra tunes, extras mill about stage, audience settles into the film set atmosphere. |

Attention must be paid to the untold story of the Italian Opera. A United States Naval Officer chooses a 15-year old girl to be his temporary wife while he pulls duty in Nagasaki, Japan. Pinkerton, the officer, can do whatever the hell he wishes in this Japan, abetted by a local Pandarus who, for 100 yen, fans out a foto gallery of alternative Cio-Cio-Sans, just pick one that suits your whim.

The local US Consul plays a major role in Pinkerton’s rape of the Japanese girl, endorsing the sham marriage colluding by running interference, like paying the rent after Pinkerton ships out for home, and keeping the boy’s birth a secret.

The child feels old, at 15, and considers the marriage arrangement her life’s greatest beneficence. Cio-Cio-San, Butterfly, loves Pinkerton with romantic teenager passion. Act II sees three years pass since Pinkerton was in town, and Butterfly sings the loveliest aria in grand opera, a daydream of her husband’s return, like Penelope probably sang over her ten years of absent love.

Then Pinkerton’s ship comes in. Pinkerton brings the blonde wife, Butterfly has been tossed aside. When the Lieutenant learns he is now a father the Consul arranges for the Mrs. to steal the child and take Butterfly’s son to the USA where can mature to be like these people.

Butterfly accepts that Pinkerton and the Mrs will take Butterfly’s son from her. Punto final. Cio-Cio-San, surrendering to her complete powerlessness, kills herself.

That’s, more or less, the untold story behind the magnificent tragedy of Cio-Cio-San, known as Madama Butterfly, sung in grand opera style as written by Puccini in 1904. In the Los Angeles Opera Company’s production running now at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the year is 1930-something. A movie company is making a movie of the Opera.

Audiences get to watch the Opera being performed for three cameras on a sound stage in a bygone Hollywood era. Making a movie in the old days and doing in front of a live audience, creates visually useful tools for enjoying a live performance. Why the 1930s, when the era’s censorship outlaws movies about miscegenation?

Take a seat. Lights, camera, action, Hays Code repression. None of these concerns are obvious on stage. This perspective is in the night’s program. You don’t have to know this to enjoy the wondrous photography on the supertitles screen.

|

| Far balcony-sitters get the same Opera the big-ticket buyers get. |

It's all make-believe, except the imperialism part. The full house at the Dot Chandler were not interested in anything but the spectacle and immersion in Director James Conlon’s portrayal of this classic opera with Karah Son in the role of her career.

https://www.laopera.org/performances/2025/madame-butterfly

The movie gimmick works in its own fashion.

At first glance, projection distracts. Maybe rock concert fans aren’t fazed by the large teevee screen. The Hollywood Bowl does it to good advantage. At LAO’s event, singers and set take second place to the giant black and white stream of the movie-in-progress. Two camera operators work near the apron.

Director Conlon uses his camera angles effectively. One scene his lens positions singers in the same frame behind one another in a dramatic visual construction of a trio. Up in the nether regions of my affordable seat, the trio stands left to right across the vista. The singers, tiny manniquins from Door 42, fill the screen above the stage. Eyes sparkle, brows contort, lips form sounds and mouths hurl melodies the 200 feet to my ears.

Light travels faster than sound. That deeply satisfying closeup an artist like Karah Son exerting all her instrument has to give comes with a delay. Up against the back wall, Son’s lungs and interpretive power on screen occur like lip sync. Her lips move on screen. Audiences hear her song a fractionate moment after Son's mouth has completed the note. Audiences up here have to listen slower so the disconcerting delay doesn’t too greatly diminish the wonder of powerful singing.

|

| Intense lighting emphasizes the chorus' colorless costumes |

Chorus costumes feature variations on high contrast dark and light patterns to produce pleasing greys or shadowed texture in the B&W movie screen. Only Cio-Cio-San wears color. The maid dresses in dingy grey. Pinkerton wears dress whites. The Consul’s brown suit and skin don’t stand out against the B&W colorscheme of the rotating set; his powerful voice does all the work.

Years ago, I had seats on the main floor. People now in my seats probably went home with sore necks, the compelling lighted screen would have had their heads repeatedly pivoting up to see the action and back down to the stage to see what the whole scene looks like in real life.

No one is compelled to see Madame Butterfly at the Dot. Just like last year's hit, El último sueño de Frida y Diego, it's a choice. The Opera’s a fantasy not a documentary. Don’t subsume rage at Puccini’s age-old literary patriarchical values driving the conceit of the story. One could compare Romeo and Juliet, or Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyda, or Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, then enjoy spirited discussions with fellow opera-goers--or people forming opinions reading LAO’s euphemistic words about some really crappy twentieth century values on that stage.

Maybe Director Conlon intends the 1930s anachronism as a subtle form of patriotic subversion? I shouldn’t have read the program and let the setting be the setting. Audiences making the trek to the top of the hill overlooking Gloria Molina Grand Park will decide if it matters beyond the pretty pictures.

Multitask, gente. It works. I hold some critical thoughts in one part of attention. I use other parts of the experience to listen to the music, drink in the spectacle, and live three hours in artful fantasy. Everyone sings whatever they have to say. A full orchestra plays the music in a sunken pit. Costumes and staging deliver their own arte. The music’s sung in Italian. English supertitles scroll above the stage on that big silver screen. It's the Music Center where Bunker Hill used to be.

Opera’s a Big Date Night for couples who enjoy special nights out. Órale, this one’s special.

Now, through October 13, 2024. (link)

https://www.laopera.org/performances/2025/madame-butterfly

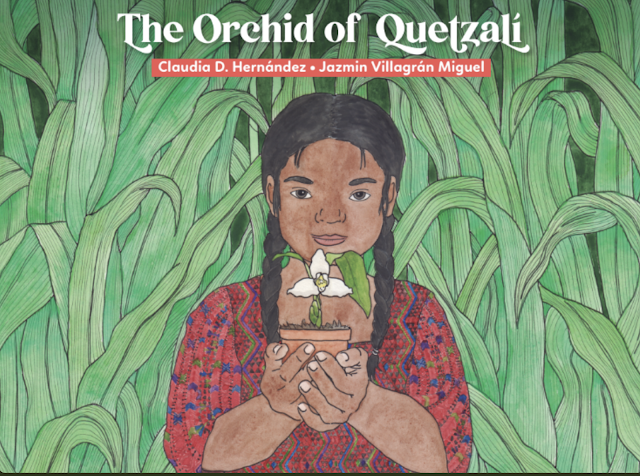

Recommended Reading: The Orchid of Quetzalí by Claudia D. Hernández

You're 7 years old when soldiers give your family 24 hours to vacate your mountain eden. This is no country for you. You take what you can carry and head north to a join a relative in Los Angeles.

That's the story Claudia D. Hernández weaves for her character, Quetzalí, in a trilogy for early to capable readers. Quetzalí is one of those books that belong on every classroom shelf. I would have loved using Quetzalí with children I was privileged to tutor in a local elementary school.

Kids see themselves in Quetzalí, or they see the kid at the next desk, or the people next door. The story opens a reader to discussions of history, migration, language, culture, natural wonders. The orchid element raises the latter issue.

Quetzalí takes her name from the jungle bird at the brink of extinction. So is the white orchid the child brings on the journey. The people of her mountain home are at the brink of extinction, too. Even if you don't explain this to a kid, the kid will "get" the metaphor.

With lush illustration by Jazmin Villagrán Miguel, Quetzalí, and its two sister titles forthcoming, make not only a valuable classroom resource, the trilogy belongs in a child's hands at home. Nothing motivates a developing reader like a book that mirror's the kid's own experience.

1 comment:

Excellent analysis of this operatic event and its presentation as basically a play within a play.

Post a Comment