Michael Sedano

A literary anthology can be a snapshot or a portrait. Both supply value. Some snapshots present a marvelous glimpse of what the world looks like in that 1/250th second slice of time. Here, time and light come to a halt in mid act with no inkling if unheard pipes will trill or squeal. A studied portrait, in contrast, represents an artist’s determination to expose depth of character, make a significant statement about time and idea through an image that reaches beyond that 1/250th of a second exposure, out of the future through the present and into the past.

A literary anthology can be a snapshot or a portrait. Both supply value. Some snapshots present a marvelous glimpse of what the world looks like in that 1/250th second slice of time. Here, time and light come to a halt in mid act with no inkling if unheard pipes will trill or squeal. A studied portrait, in contrast, represents an artist’s determination to expose depth of character, make a significant statement about time and idea through an image that reaches beyond that 1/250th of a second exposure, out of the future through the present and into the past.¡Ban This! is a snapshot. Editor Santino J. Rivera cast a wide net and attracts dozens of new and emerging voices. Rivera buttresses the nouveau with the solid quality of several well-respected artists. In putting the collection together, as any editor, Rivera treads a hazy line between all the stuff that’s fit to print and selecting only superb exemplars of the best stuff.

Aside from making a great gift,¡Ban This! will occupy a valued space in anyone’s reference shelves. The collection has some literary gems, particularly among the poets and a couple of de rigueur essays. The editor believes the collection informs a notion of an arroba aesthetic, that weird spelling that supplants gender inflection with unpronounceability. This aesthetic finds a tongue with the publisher’s disclaimer, that the company “assumes no liability should you get your feelings hurt. Except you. And you. And you, too.” The attitude is more the editor’s than most of the collected writers.

Do Xicanarrobas bleed politics, nurture anger, shake fists at power structures, live for confrontation? Not really. The editor makes a big deal about orthography and readers like me who reject that arroba barbarism. Then he avoids analysis, deferring to the contents of the anthology as the “definition” of “Xican@” literature.

What then, to make of a Chicana writer like Gina Ruiz, who wants to be funny? Ruiz’ playful fiction “Chanclas and Aliens” blends barrio iconography with weird science and the familiar refrain no good deed goes unpunished. Another writer, Xicano X gets wrapped up in his own hang-ups and strives to be offensive as a strategy for getting attention through asco and scatology. Where is the arroba aesthetic in that?

Despite the editorial shortcoming, ¡Ban This! makes a valuable contribution to a bookshelf or library. Rivera’s assembled a magnificent variety of work valuable for the breadth of coverage, from poem to political science to science fiction to anthropology and history.

Half the book’s 332 pages publish short poems. Opting for quality, the first two poets out the gate are Francisco X. Alarcón and Luis Urrea.

Alarcón’s bilingual work features intricate architecture that defies conventional use of the page. Instead, an Alarcón poem may be read from left to right or top to bottom, or alternatively, read an English stanza then its corresponding Spanish stanza, plus the left/right/top/bottom opportunity. Alarcón invests his poems with multiple possibilities and resources, at once thoughtful and diverting.

Urrea’s lead poem, “Arizona Lamentation,” is a spectacularly difficult poem. Opening with the strident phrase, “We were happy here before they came”, the persona expresses resentment of newcomers. Except the persona speaks in an anglo voice, projecting fantasy history onto the land, “Then their envy, their racial hatred / Made us build a border fence / To protect our children. / But they kept coming.” Just as the alarmed reader is about to toss the book out the window at that crud, the persona shifts, “But their wagons kept coming and coming. / And their soldiers.” And in closing, the one voice again becomes displaced by the other, while between the lines their sentiments echo one another’s fears. What an intractable mess.

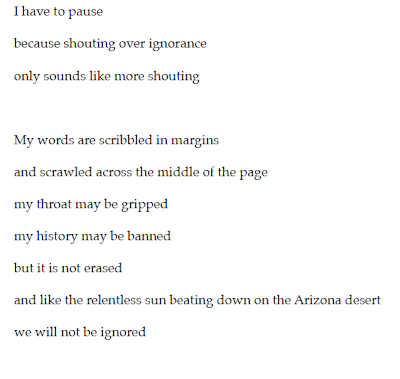

Oddly positioned, near the end but not the final piece, is Odilia Galván Rodriguez’ title piece, “¡Ban This!” The piece reflects well off Urrea’s. Spoken in a raza voice, Rodriguez’ poem is one of puro affirmation. Addressing book banners, the poem illuminates qualities and beliefs supporting raza peoplehood, not a subversion of the anglo internal colony. The poet’s restrained anger sounds loud and clear. It doesn’t need a gimmick, an “X” or an arroba, to declare unequivocally, “words live / we remember / them, our love, our stories ~ / history, cannot be erased / not banned”

Chicanas Chicanos write a lot of poetry. Maybe that’s why ¡Ban This! has such a heavy proportion of it. The prose work--fiction, memoir, essay—offers a rich potpourri of information, but suffers from editorial neglect. As an editor, Rivera needed to get after sloppy spelling and stilted construction. Instead, it appears the editor simply cut and pasted submissions, favoring laissez-faire publication rather than exercise the editorial authority writers deserve.

Two seminal essays merit widespread reading. Roberto “Dr. Cintli” Rodriguez’ “From Manifest Destiny to Manifest Insanity,” and Rodolfo Acuña’s “Giving Hypocrisy a Bad Name: Censorship in Tucson.” The essays are scholarly, and entirely readable. That’s less true of other prose work in the collection.

David Cid’s “Silent No Longer: The Visual Poetic Resistance of Chicana/o Cinema in the Experimental Films of Frances Salomé España” is a recycled term paper. Cid gives interesting information but it’s nearly indigestible owing to that seminar paper style. Cid promotes the “Chicana / o” construction, rather than the arroba. In one sentence the trick gets away from Cid and his editor; one woman is labeled a “Chicana / o”.

Del Zamora’s Los Angeles Times piece, “Where Are The Latinos In Films, TV?” is one of those pointless Op-Ed pieces that complains only to close with irony instead of constructive ideas. “It’s either that or stop purchasing tickets and renting videos of movies and television shows that do not include us. After all, as one Hollywood executive explained to me, ‘We don’t have to put you in movies…there were no Latinos in Gotham City and you still came.”

Miguel Jimenez, “Veterans Empathize: HB2281 and The Attack On Mexican History And Culture” illustrates the cyclical nature of Chicana Chicano history. Jimenez’ memoir of his Iraq service echoes draft-era complaints that military service validates one’s identity as a Unitedstatesian, even in the face of rejection and exclusion.

Maria Teresa Ceseña brings a homily on self-identity, “The Turtle Caught in the Fire.” She opens with a powerfully composed non-fiction equivalent of spoken word art. Here Ceseña the academica advances a feminist rationale she defines as “oppositional consciousness”. She follows that introduction with her poem, “Piecing It Together,” then spins off from there describing a life experience in much the ways anthologies describe the status of a literature. Put the shards together under a blazing sun and for one moment achieve a freeze frame of where everything is, in relation to anything else. Except the point of the essay curiously is about giving up. Ceseña encourages dreamers that it’s never too late to change by giving up an old dream in view of what’s hot right now.

This reader is grateful for the end-wrapper from Mario Barrera, “Science and Religion in a Border Town,” a generous helping of humor to lighten the weight of the deadly earnest essayists who’ve preceded Barrera’s memoir.

Andrea J. Serrano's "Lament" exemplifies how Chicanas Chicanos respond to banning books. Not with a big knife in a steady hand, but a broken heart and a loaded ink pen.

La Bloga friend Frank Sifuentes' body is shutting down, surrounded by love and family, as it should be.

Frank's daughter sends along her father's news. I'm sure Frank would have preferred to deliver the news en propria persona, with a joke and a winding tale with a twist at the end. Nos wachamos, Frank.

The crisis. Oscar Zeta Acosta refuses to go inside, where a full house awaits the Brown Buffalo's reading. Outside, spectators mill about in panicky unease. The door opens and Frank steps outside. Zeta explains his refusal to go on. They negotiate and Zeta enters to take the stage.

| Tomás Atencio, Frank Sifuentes, Alurista, Oscar Acosta. Juan Felipe Herrera in background, and unidentified USC co-ed. © michael v. sedano |

Ay, Frank, so many stories, so little time.

Here's Frank at the 2010 Festival de Flor y Canto. Yesterday • Today • Tomorrow, that reunited dozens of artists from that first Festival de Flor y Canto.

You can hear Frank read at 1973's floricanto by visiting the USC Digital Library archive.

Mailbag

Barrios Interviews Junot Diaz

La Bloga friend Gregg Barrios advises his recent interview with author-on-the-ascendancy Junot Diaz is at the Los Angeles Review of Books site.

La Bloga friend Gregg Barrios advises his recent interview with author-on-the-ascendancy Junot Diaz is at the Los Angeles Review of Books site.It's a rewarding interview between two long-time compañeros, for, as Barrios points out:

Reading Díaz is to discover a new voice in American lit that continually amazes as it informs, his text a vast storehouse of literary references, footnotes, and genre-bending throwaways. His groundbreaking use of Spanish without italics or translation is deeply refreshing to Latino readers, as it is to any reader who recognizes it as part and parcel to the bilingual Latino experience.

Closet of Discarded Dreams at Tia Chucha's September 14

Tia Chucha's Centro Cultural and Bookstore hosts bloguero and La Bloga founder Rudy Garcia on Sunday, October 14 starting at 2:00 p.m. Located at 13197-A Gladstone Ave, Sylmar, California, the popular bookseller and events headquarters provides a welcome atmosphere for a steady parade of writers.

Garcia will be at the Latino Book & Family Festival on Saturday, as noted in Monday's Daniel Olivas column.

On-Line Floricanto for Nine Ten Twelve

Joe Navarro, Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo, Fernando Rodríguez, Tracy Corey, Victor Avila

“It Must Be the Chicano In Me” Joe Navarro

“Search and Recovery” Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo

“Indocumentado” Fernando Rodríguez

“Listen” Tracy Corey

“Ban This Poem!” Victor Avila

It Must Be the Chicano In Me

Joe Navarro

It must be the Chicano in me

But when I listen to the music of

Lila Downs singing from the depths

Of her soul or Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlan

From Jalisco, the land of my ancestors

Celebrating el 16 de septiembre

I feel proud to be me

When campesinos demand fair wages

That their invisible hands have earned

Or when people openly declare,

“I am undocumented!” fearlessly

Yet knowing they will be forcibly

Detached from the only lives they know

I feel their plight and injuries

When I hear La Raza speaking

English, Spanish and Spanglish

At the mercado or in the park

And when I see mothers bringing

Their children to school in one hand

With younger siblings in strollers

I feel at home in my comunidad

At every tardeada, fiesta, baile or concierto

Where people dance and enjoy music

At marches where workers honor the

Tradition May Day and workers’ rights

At every gathering that honors heroes

Martyrs and luchas for human dignity

I feel the aspirations of my people

I extract pride from holidays

Inspired by people’s desires for

Self-determination and independence

And from magnificent murals and poemas

Honoring our indigenous traditions

And struggles to escape domination

…It must be the Chicano in me

Search and Recovery

Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo

for Brooke

is not like search and rescue, not like the 10 o’clock news,

not like blond daughters sucked out through windows

in the dark night. There is no line of volunteers

combing the woods at the edge of a peach town,

no fleet of police dragging the lake, no pencil sketches

or time-stamped videos of dark men in black hoodies,

no midnight vigils blurred by hundreds of burning white candles,

no posters, no milk cartons, and no alerts.

There is plenty of desert silence between two women

scaling the Atascosa mountains like two specs of dust.

They search for a young man shot by his coyote and discarded

by a wash with cement blocks and black kites fallen from the sky,

or maybe black tires taken from a truck. They exhaust

unreliable reports in a futile act of deciphering hazy, hot landmarks.

They hike and carry what supplies they can slung over backs:

extra water, socks, electrolyte pills, a couple of apples, peanut butter.

Before the sunsets, they set up camp beneath the sky

and wait for the sun to rise so they can try again.

In the day, they search for what remains,

In the night, they fear what remains will look like,

and each woman secretly holds hope close to her chest

that if she crosses a bundle tomorrow, it will once again be branches.

Indocumentado

Fernando Rodríguez

Colgué el teléfono y una lagrima rodo

Del otro lado de la bocina mi hijo el mas pequeño

Aun residen en México,

Como quisiera poder abrazarlos,

La vida si que es dura

No se puede tener todo

Pero valdrá la pena, si le hecho ganas y me supero

Al colgar ese teléfono

Le pedí a mi dios valor, fuerza y paciencia

Para lograr lo que el güero tiene

Su familia a su lado

Veo como todos los días gente se divorcia, separa y junta

Sin saber el verdadero valor de una familia

Sin entender la dedicación,

Yo no soy nadie pa’ juzgar

Solo relato mi versión

Mañana es lunes y otro día de trabajo

Otra vez me la rifo manejando

Iremos para el campo

Pizcando paso mi vida

Para ganarme la plata

Con la que vive mi familia

En mi pobre tierra mexicana

La vida no vale nada

Y menos acá

La gente le da importancia

A un pedazo de papel

Que a la misma vida

El cuello blanco controla todo

Sin ensuciarse las manos,

¿Y yo?

Un simple campesino

Que me ensucio de barro

¡No controlo nada!

Tiene más poder un perro

Por tener esos papeles

Desearía ser importante

Para ayudar a mi gente

El teléfono acorta y alarga mi dolor

Escucho a mis seres queridos

Pero no los puedo abrazar

Tengo que ser conformista

Para poder aguantar

La dificultad no es vida

Pero no hay para mas…

Listen

Tracy Corey

~ for my grandmother, Almira Miller (1924-2011)

Listen to your grandmothers. They are the voices

of your bones whispering to your wings

before grace has found you. When she warned

of that boy, hear her history, and when she closed

her eyes and kissed the baby, see her heart

wink at her feet for the blisters that delivered such beauty.

Listen to her cooking, informing you of the beauty,

of the beaches and the barrios that feed the voices

calling from the winding roads that lead to her heart

and breathe through her veins, giving air to her wings

that felt, when the nights got so dark, a longing that closed

the days with a notion of something that warned

her to listen. And when she did, she was warned

of a life begun again in subtitles, but a life of beauty

without the hardship of hungry days and closed

borders where her children spoke with their voices

bouncing in boxes rather than sailing on wings

that aren’t too heavy from the days to beat in the heart

that can listen because it can hear. And planted in her heart

she wrapped the deepest seeds of home’s garden, warned

of the days when nothing would feel so urgent as wings

to take her home, to the backbone of beauty,

and even the sorrow, just for the familiar voices,

enough to sometimes make you forget the closed

borders. Listen to the seeds she wrapped in the closed

petals of the bright flowers she planted in her heart

and you’ll hear the stories of so many, their voices

building a homesick choir that when warned

of wasted despair all they can recite is, “Beauty

is beauty, even when it flies on broken wings.”

Listen to their song, delivered on the aging wings

of your grandmothers, who know the secret to closed

borders is traveling hand-in-hand with beauty

in the exploding seeds of home’s garden, the heart.

And just for good measure, let despair be warned,

the secret is carried in the many voices

of secret-keepers who, despite being warned

by sorrow, listen to history and sing with their wings.

Ban This Poem!

Victor Avila

Before it is read

And the seed of its ideas spread-

Ban this poem.

For though subtle and unassuming

Consider this a warning

for those hard of heart and fearful of change.

Ban this poem-

Create a law and demand it!

Or it will be a curse to those who live by the tenets of hate.

Xenophobes and war-mongers

this is your chance

to rip up these thoughts before they escape.

Yes, ban this poem

before it is nailed into the door of our consciousness

or a transmutation will take place.

It will certainly gain entrance

and disrupt the lives

of those wrapped up in a barbed wire embrace.

For it does what a poem

is supposed to do

and tap into a humanity we thought once lost.

It is a glimmer of new awakenings,

and a fulcrum of tolerance.

It is a blanket for the homeless should the cold set in.

So ban this poem-It is dangerous.

And out of place with society's values.

Lock it up in the darkest of prisons for it is a contagion of enlightenment...

...And a missive of acceptance...a dispatch of hope.

So ban this poem.

YES, BAN THIS POEM!!!

BIOS

Joe Navarro, Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo, Fernando Rodríguez, Tracy Corey, Victor Avila

“It Must Be the Chicano In Me” Joe Navarro

“Search and Recovery” Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo

“Indocumentado” Fernando Rodríguez

“Listen” Tracy Corey

“Ban This Poem!” Victor Avila

Fernando Rodriguez writes from Mexicali, Baja California, Mexico. He is a 25 year old poet who believes in freedom, equality and despite racism in any of its many forms. This poem was written to create conscience about suffering of immigrants in this land.

Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo is a high school teacher and native Angeleno. She is the creator and curator of Beyond Baroque’s monthly reading series Hitched and was nominated for a 2010 Pushcart Award. Her manuscript, The Meditation for the Lost and Found, is in part inspired by 10 days she spent patrolling the Arizona-Mexico border volunteering with the direct humanitarian aid group, No More Deaths. Her poetry has been published in The Los Angeles Review, CALYX, and PALABRA.

Tracy Corey has lived in Los Angeles, Seattle and traveled throughout Mexico. She is the recipient of First Place in Poetry 2012 in the award-winning literary magazine, SandScript, and her photographs have been exhibited in Arizona and been used as cover art by an independent press. She has studied creative writing at Antioch University, Los Angeles, and the University of Arizona. She is the owner/operator of a small business that, among other things, edits and proofreads manuscripts for authors already published and/or seeking publication. She currently lives in her hometown of Tucson, Arizona.

Victor Avila is an award-winning poet. Two of his poems were recently included in the anthology Occupy SF-Poems from the Movement. He is also a writer and illustrator. Three of his ghost stories were recently included in Ghoula Comix #2.

No comments:

Post a Comment